Not everyone reading this page is likely to be old enough to remember when it was entirely possible, if one went to a restaurant for a meal, that the napkin dispenser might include a tiny vending machine in the middle.

One put a penny in the slot at the top, then depressed the lever, and out would come a slip of paper. On one side would be the designation of a playing card... and your fortune; on the other side would be the anser to a Yes or No question (preferably worded so that a Yes answer would correspond to the preferred outcome).

Of course, such a device is hardly calculated to inspire awe. It's pretty obvious it will just give you the fortune that happens to be at the bottom of the chute, and there's no particular reason to expect that it will be the one corresponding to your destiny.

Of course, I suppose one could think that the Universe is set up so that the random shuffling of the fortunes, as they're placed in the machine, and the random events that lead one person to enter a particular restaurant at a particular time, and sit down at a specific table... could all work together to cause people to get the fortunes meant for them!

In fact, a noted psychiatrist, Carl Gustav Jung, actually formed a theory of the Universe working this way, called synchronicity.

But I'm afraid that I, for one, don't even feel terribly inclined to talk about this...

At penny arcades, one could get a slip of paper with one's fortune from a machine which had an automaton behind glass that appeared to be reading the cards to find one's fortune before a slip of cardboard with one's fortune came out.

This was more impressive, but it was still clearly only for amusement, and not to be taken seriously.

And then there's...

Before the age of electronics, one other item that could be quite impressive in appearance is a clock.

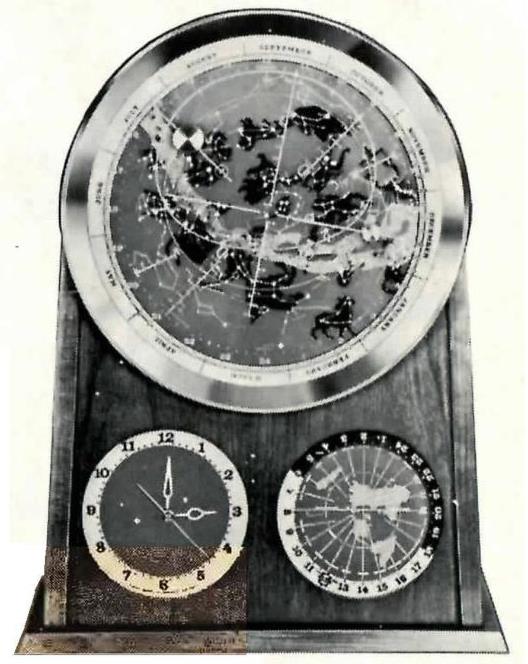

Thus, on the left is a replica, on exhibit at the United States National Museum, of the Astrarium, an early astronomical clock designed by Giovanni Dondi and completed in 1364. It was able to show the positions of the Moon and all the planets, as well as the time and date.

Somewhat less ambitious was the Spilhaus Space Clock, shown on the right, which provided the time on the lower left, world time on the lower right, and a main dial showing sidereal time and the position of the stars in the sky. This was offered for sale in the 1960s for the rather pricey sum of $250.00, particularly as its internal construction cut costs with the use of rubber belts in some spots rather than gears.

Advancing to the modern age of electronics, here on the left is a picture of the world's first atomic clock. It used an ammonia maser to produce a constant frequency; however, it was only a proof of concept rather than a practical device, as it was not as accurate as a quartz oscillator.

The clock surmounting the device is not an indicator controlled by that frequency; it's only an ordinary electric clock. A 50 Hz frequency was produced by frequency dividers from the output from the maser, but as mains current in the United States is 60 Hz, arranging to drive the clock from it wouldn't have been practical.

In the photo, the individual on the left is Dr. Edward U. Condon, then the director of the National Bureau of Standards, and on the right is the clock's inventor, Harold Lyons.

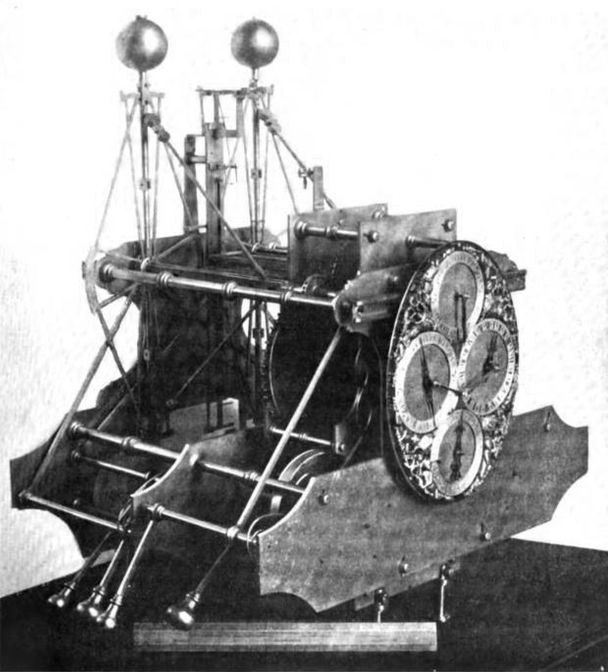

And a clock that is truly awe-inspiring in appearance, also coming out of a quest for a more accurate determination of time, is the first of the marine chronometers designed by John Harrison for the purpose of allowing ships at sea to accurately determine their longitude, as depicted in the image at right from a book published in 1923.

Rupert T. Gould, who cleaned and restored Harrison's first and fourth chronometers, enabling the fourth one to once again run, noted that modern marine chronometers owe more to the later design of Pierre Le Roy than that of Harrison's fourth chronometer, as in his design, several components were fundamentally redesigned in a fashion that eliminated potential sources of error completely instead of merely compensating for them.

However, it may also be noted that before beginning his work on the marine chronometer, John Harrison published a pamphlet in 1775 describing proposed improvements in accurate wall clocks; these ended up not being tried at the time, but much later, in 2015, Martin Burgess' Clock B demonstrated that these improvements would indeed yield, as promised, a pendulum clock that would be in error by no more than one second in a hundred days.

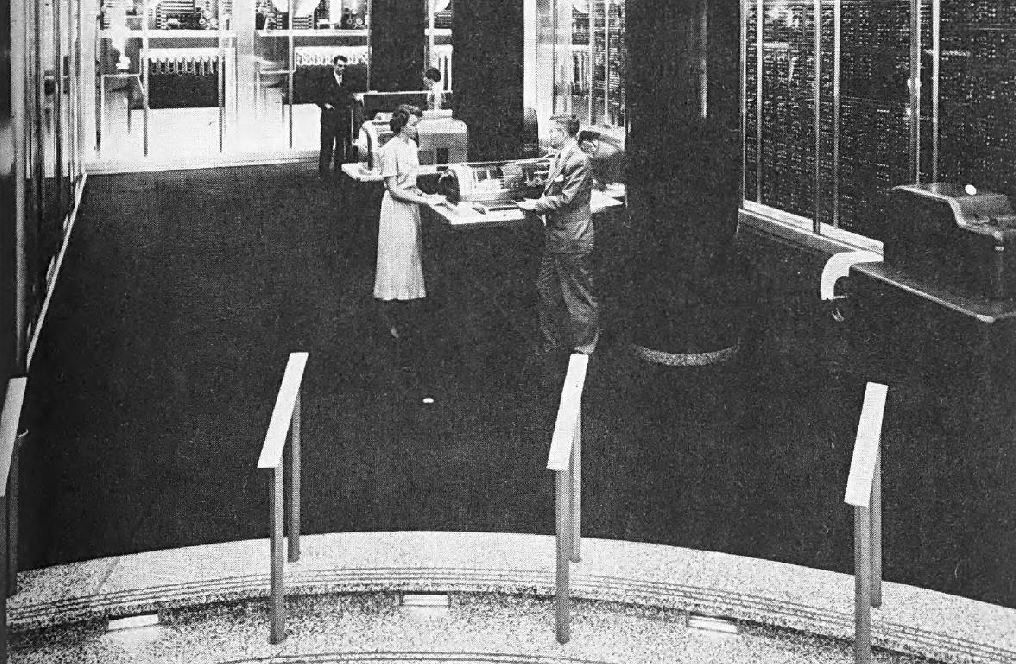

Now, if one comes face to face with something that looks like this:

or like this

one could be impressed enough by its appearance to wonder if it might harbor within it the capability to pierce the veil of futurity.

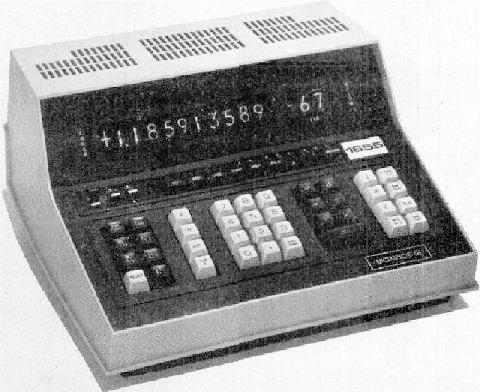

On a smaller scale, how about a desktop programmable scientific calculator with a Nixie tube display, such as this Monroe 1655?

Of course, though, these days familiarity with computers has bred, if not contempt, at least a more realistic acquaintance with their capabilities. But whatever we don't understand, if it looks complicated enough... presumably has some purpose commensurate with its complexity. Wondering what that is, our imaginations may run wild.

But speaking of computers, instead of one being awe-inspiring by being imposing, it's also possible for one to grasp our imagination by being cute. While I admit it might be going out on a limb to claim that the HP-85 was the cutest computer ever made,

I do think that it is at least one of the top contenders.

Less expensive than an old-fashioned mainframe computer,

would be a fancy short-wave radio.

With its multiple tuning scales for the different bands on which it provides reception, it looks impressive enough. And, as it lets one listen to voices half a world away (and without use of undersea cables, or other infrastructure providing connecting wires) it does indeed do something that was once regarded as amazing and impressive.

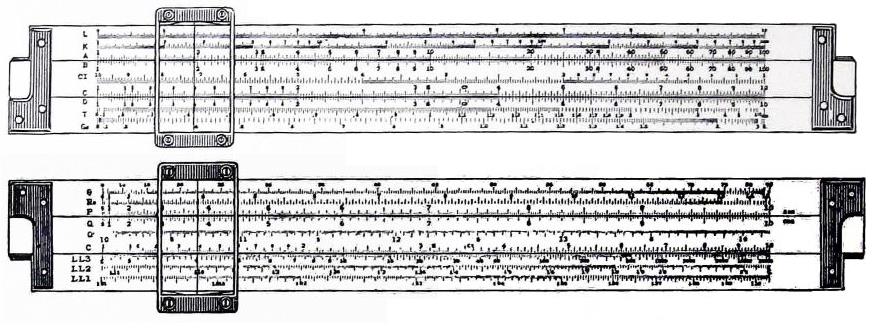

Even the complicated scales on an advanced slide rule

can inspire feelings of awe and wonder - and yet, it's at bottom only a device for adding distances on two scales, by allowing one to slide one of those scales against the other, and including a cursor to measure distances on any part of the rules.

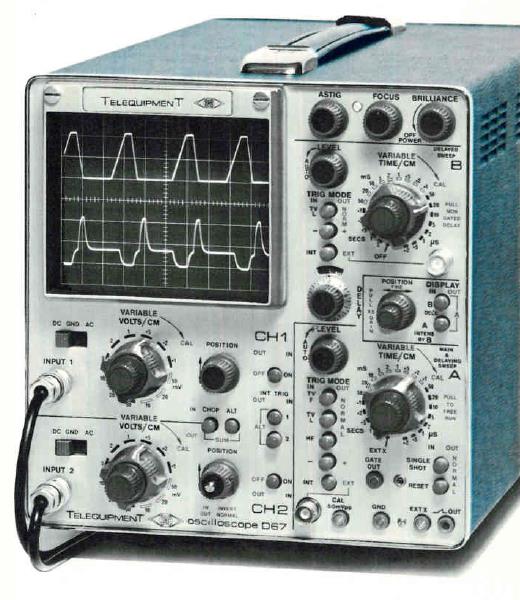

If I am going to talk about things which look strange, mysterious, and awe-inspiring, certainly I can't forget about the oscilloscope. Usually, it is fairly advanced pieces of electronic equipment that require one of these to be connected up as a component, so that one or another of the signals that move within it can be viewed directly, so it's not at all surprising that in many science-fiction movies or shows, an oscilloscope screen is present to make a piece of apparatus look all the more impressive.

In any case, though, given the ability of the modern desktop computer with an Internet connection to provide endless hours of entertainment and information... surely it should be the subject of awe and wonder... but it is all too familiar and accessible for that!

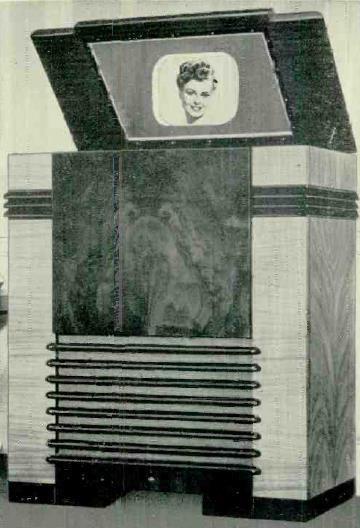

And then there's this awe-inspiring and astounding device that existed many years before computers entered the home,

which could let you see, in the comfort of your home, news from half a world away, or hear musical performances from the world's greatest orchestras, or allow you to watch dramas, plays, and movies!

And the rapid pace of technical progress, in a few short years, allowed people to watch their favorite television programs in full color, starting in 1954; the image at right is a somewhat later-model color television from 1956. It is still, however, a fairly early-model color TV, as it can be seen from the image that for color televisions, at first, it was necessary to revert to round picture tubes, while black and white televisions at that time already had rectangular ones.

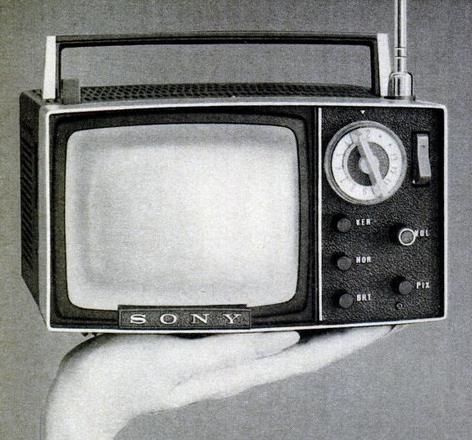

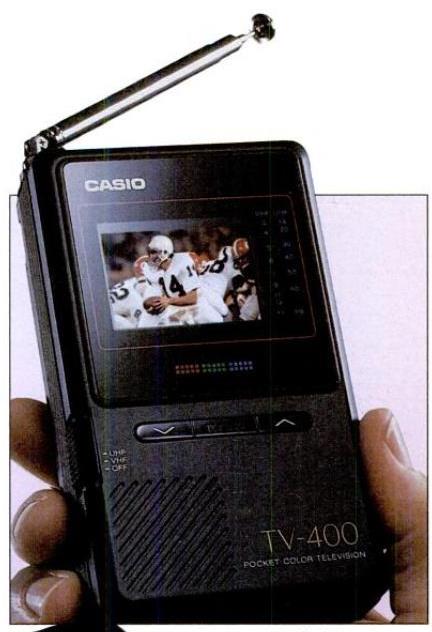

And then, when the transistor became available as an alternative to the vacuum tube, it became possible to design a television set so small that it could be held in one hand...

Of course, though, wonders did not cease at that point. Eventually, as it became possible to replace the cathode-ray tube by a liquid-crystal display, and integrated circuits displaced discrete transistors, it became possible to design a color television set that could be put in one's pocket and run on batteries.

But then, shortly after, analog TV was replaced by digital TV, and pocket televisions designed for the new signal did not get made. So there can be disappointment as well as awe in the world of high technology.

Well, at least at the time. Currently, one can indeed find small portable digital televisions, at least on Amazon.

If one is going to talk about television sets that inspire awe and wonder, however, how can I possibly forget to mention one television set the futuristic design of which has amazed people for decades afterwards? Thus, on the left is pictured the Philco Predicta television, this one from a 1958 advertisement.

And it is also not necessary to go all the way to Japan to find a miniature television set made possible by the transistor. Thus, on the right is shown another Philco creation: the Safari, from 1959.

This portable television set, capable of running on batteries, is eight and a half inches wide. The picture tube, however, is only two inches wide. However, an optical system enlarges its picture to one with a fourteen-inch diagonal.

What appears to be the screen of this small television is, in fact, essentially the opening of an eyepiece through which the picture, appearing to be four feet behind the set, can be seen.

By putting the image deeply inside the set, this kept it away from stray light, allowing the sunshade still present above the window to be sufficient to allow one to watch television with the set in bright sunlight, the sunshade still being needed, as the window could still reflect glare.

British 405-line television broadcasting began in 1936, but it was not until 1939 that regular television broadcasts began in the United States, on April 30, in conjunction with the New York World's Fair.

The pre-war television broadcasts in the United States did not follow the 525-line postwar standard, but instead had a 441-line picture; they still had 60 fields and 30 frames per second with interlacing, and television channels were still 6 MHz wide.

We met the Philco Safari portable television above, that used a somewhat unusual projection system to achieve a large image from a small picture tube. Some of the earliest television sets were also a little bit unconventional in their arrangement, although only one mirror, and that one flat, was involved.

For example, on exhibit at the RCA pavillion at that fair was their TRK-12 model television, pictured at right.

Its screen had a 12-inch diagonal. There was also a very similar TRK-9 model, with a direct-view 9-inch screen.

Several manufacturers made early television sets in the same configuration as the TRK-12. Having a mirror, nominally at a 45-degree angle, at the top of the set allowed the picture tube to be mounted vertically.

This let the cathode ray tube of the television be flat in front, for a higher quality picture, with a smaller deflection angle.

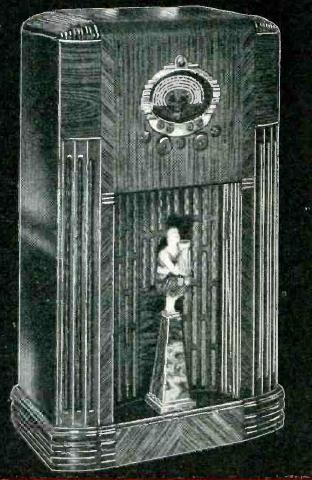

And before the television came along, devices like those pictured at left inspired awe and wonder. Hearing the voices of people far away in one's own living room; listening to music played in one's city, or to people speaking perhaps at the other end of the world, as the radio pictured is a model that can receive programs on the short-wave bands.

When radio was new, when it was still difficult to design and manufacture radios, when they were still expensive, it's only natural that they would inspire some degree of awe; and just as natural that when they became an inexpensive and commonplace item, that would no longer be the case.

Now, what this page is not is a complaint that we have become just too blasé about everything these days.

While it is natural to stand in awe of things we don't understand, surely it's better to have understanding instead of to dwell in ignorance; to actually know what the impressive-looking machines around us are actually for, and what they can and can't do.

Ah, no. Instead, this page is a lament about something else... perhaps the exact reverse of that.

Why are not there things to be found that are as amazing and wonderful in their capabilities as we mistakenly imagined other things to be, because of their appearance?

But, come to think of it, perhaps that is even more unreasonable.

To stand in awe of a complicated apparatus, because we don't understand it, and it seems as if strange and mysterious things are happening within it, is at least possible, but for there to be a complicated apparatus in which there actually are strange and mysterious things going on, well, that's asking for an exception to the laws of physics!

Actually, though, there is one thing in which we could legitimately stand in awe: our fellow human beings, as they, like ourselves, are conscious beings, and consciousness is truly strange and mysterious!

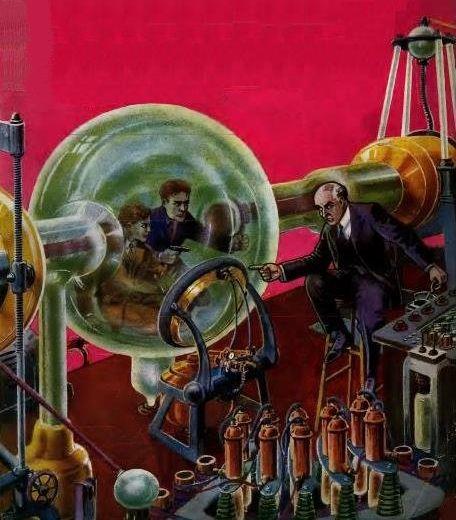

Or is it that our expectations have been spoiled, by comic books (particularly DC comics from the Silver Age) and pulp science-fiction from the 1930s (from which they drew quite a bit)... as illustrated by this artwork, from the cover of the February 1930 issue of Science Wonder Stories.

A complicated looking machine, with vacuum tubes sticking out, with plenty of dials and gauges... why, it could be a mind-control ray, or a shrinking ray, or, as in the illustration, a machine to let you see remote places without the aid of a TV camera previously placed there.

At least the artwork at right illustrates how our expectations might have been spoiled. As for the connection between pulp science fiction and DC comics of the Silver Age, I present to you:

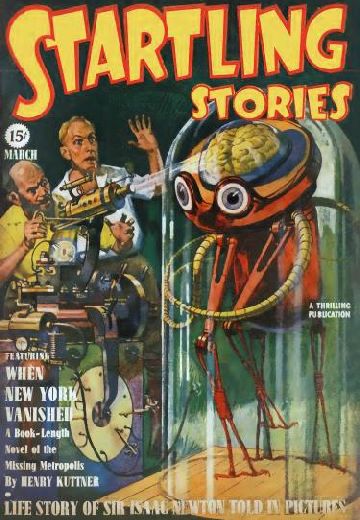

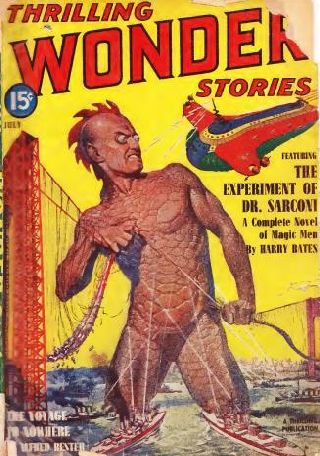

the covers of the March, 1940 issue of Startling Stories, and the July, 1940 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories.

The alien being on the Startling Stories cover strongly resembles an alien from a distant dimension who started following Jimmy Olsen around, scaring other people by its unearthly appearance, until he agreed to star in a monster movie the alien wished to make, in the March, 1960 issue (number 43) of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen. The alien returned in issue 47, the September, 1960 issue.

As for the Thrilling Wonder Stories cover, that is reminiscent of the cover of issue 53 of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, from June 1961!

In fairness, though, DC Comics wasn't the only company whose artists had old science-fiction magazines in their swipe file.

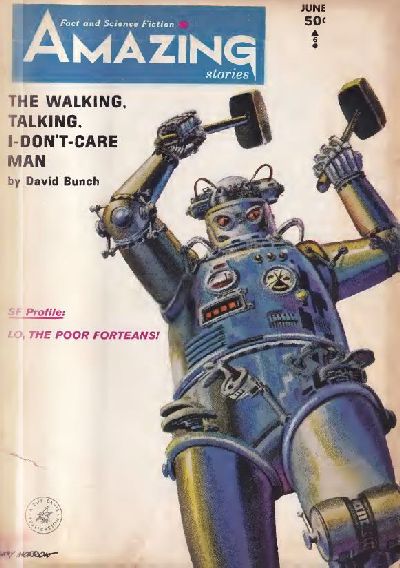

From the cover of Amazing Stories for June 1965, we see a robot... that was the basis for Voltorg, a menacing robot created by the scientist Yandroth that Doctor Strange encountered while travelling between dimensions in Strange Tales 165 and 166 after Dan Adkins had become the new artist for the series.

Well, perhaps at least at one time there were... machines that were as amazing and wonderful in their capabilities as we mistakenly imagined other things to be, because of their appearance, that is...

even if these days, any decent video card would perform more floating-point operations per second... even if actually putting them to use for serious purposes is difficult.

And then, there's this site which offers working replicas of the PDP-8/I and PDP-11/70, powered by a Raspberry PI, which both emulates the target computer and controls the front panel lights to follow what would have appeared on the originals. They were working on a similar replica of the KA-10 version of the PDP-10.

Copyright (c) 2022 John J. G. Savard