Punctuated Equilibrium

Because Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection is often misunderstood, it is not surprising that the theory of Punctuated Equilibrium, originated by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge, which addresses a fine point in this theory, is even more likely to be misunderstood.

You may recall from comic books scenes where the hero's sidekick is exposed to an "evolution ray", and becomes a "man of the future", complete with bulging cranium. (A classic example appears in the August 1957 issue of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, number 22.) For reasons that, hopefully, will soon become apparent, if a ray were invented that made people smarter, it would have nothing to do with evolution.

People were able, over many years, to make poodles out of wolves by choosing which animals would be allowed to have offspring. Thus, artificial selection can produce modified creatures.

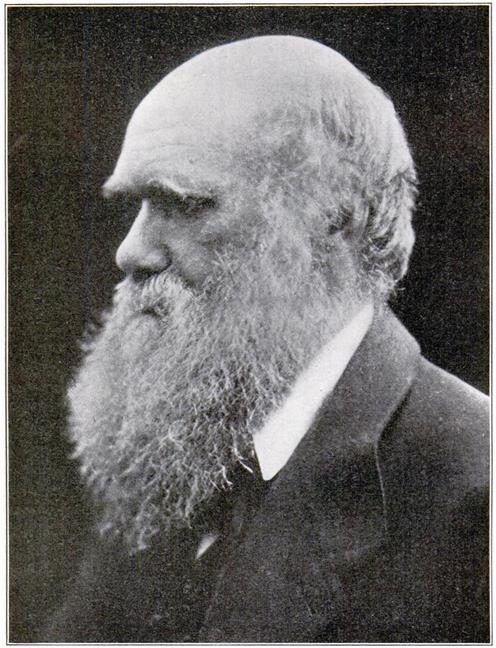

On the right, by way of illustration, appears the famous portrait of Charles Darwin by Julia Margaret Cameron, as it appeared in a magazine article from 1909. As I am now going to launch into a restatement of his famous Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection, it seemed appropriate.

By putting together the well-known observations, which were commonplace even in his day, that:

- in the wild, for many animal species only a fraction of young reach maturity and have progeny;

- among animals of a given species, some are stronger or swifter than others, or more clever, or taller, or different in color;

- the descendants of a given animal tend to resemble that specific animal;

- the characteristics and abilities an animal is born with can make a difference in its chances for surviving to maturity;

Darwin proposed that animals are constantly being subjected to natural selection; the conditions of nature are constantly choosing which animals are allowed to breed. As they do so without the consistency a human breeder might apply, and without a conscious approach to a particular end result, they effect change more slowly than a human breeder would, but they do so in the end none the less.

These three observations, as listed above, are, in my opinion, clearly not tautological. They describe something that is claimed to actually happen among living creatures, leading to real changes. The objection has been raised that evolution is based on "the survival of the fittest", and yet the "fittest" are merely being defined by the fact of their survival. That certainly does sound like a tautology. How does the account given above differ from that?

Because evolutionary theory says more than just "the survivors survive". It also claims that there is variation among the populations of living creatures, and so later generations among them will tend to survive better, always taking the best from the pool of variation (which is presumed to center on the mean for the previous generation).

Natural selection, as Stephen Jay Gould noted in one of his essays, was proposed before Darwin by Edward Blyth. But he did not propose it as a cause of evolution, but rather as a scientific explanation for the conservation of species. As the theory of puntuated equilbria also notes, if one goes out and observes a population of creatures in its natural habitat, what one will normally see are creatures that are very well adapted to that environment. Well enough that it at least appears that they are adapted to that environment in an optimal manner. As well they might be, given the limitations of what random mutations can do to living orgamisms. Then, natural selection will simply maintain this state of optimal adaptation, rather than allowing harmful mutations to gradually accumulate over time. This usually works, given a large enough local population; however, as is well known, if a population is too small, it can become inbred, allowing harmful mutations to accumulate faster than selection can remove them.

Some misunderstandings of evolution result from not understanding the simple account of evolution given above. Evolution is the consequence of an environment imposing itself upon animals through dealing out death to them; it does not happen automatically, because of some impulse to progress within living things, by the mere passage of time.

But nothing in this simple picture, as stated above, would contradict the naive expectation that, due to natural selection, that perhaps a million years from now, nearly everyone would be both an athlete such as would today be in the highest ranks of international competition, and a scientific and mathematical genius as well. Perhaps the number of people who could play a musical instrument would also have increased slightly.

In fact, however, professionals in biology do not expect that this will happen. The earliest fossil remains of our species, those known as Cro-Magnon Man, show creatures likely to have been just as intelligent as ourselves, even though they didn't have as much interesting and useful technology available to be learned as we do. They were, if anything, more likely to be physically fit, and were rather stronger than most of us.

One way to explain this would be to claim that humans had "stopped evolving", since almost all of our children grow up to become adults, thanks to the effectiveness of human technology.

Although there is some truth to the idea that the lash of selection is lighter on humanity's back than upon most other creatures, the fossil record shows that the condition of not changing very much over time, referred to in the theory of punctuated equilibria as stasis, is very much the common condition of nearly all species. Including, for the duration of their existence, the species that became extinct, and were succeeded by species we consider to be more advanced.

Does the fossil record then prove that evolution didn't happen? Perhaps it might, if all the time that existed since the beginning of life on Earth was only just sufficient, through constant slow and gradual change, to bring about the complex forms of life that exist today. However, if being stuck in traffic for ten minutes can seem like a long time, and if a new breed of dog can be developed in less than a hundred years, perhaps evolution could still have taken place if a sizable fraction of the last three billion (thousand million) years had been "wasted", at least at first glance.

Because evolution doesn't work by magic, however, but by the action of the environment upon animals, one cannot argue for some intrinsic tendency of animals to evolve by fits and starts. The theory of punctuated equilibria must have, and does have, a different basis than this.

It rests on these facts:

- A genetic change, even if it is favorable, tends to become swamped and lost if it appears within a large population of animals;

- This is particularly true of a change that works towards the creation of a new species, by making those with the change less likely to have children with unchanged creatures;

- When a population of animals is released into a modified environment, within a few hundred or thousand generations, the available changes, from among the stock of natural variation they posess, have mostly taken place;

- The kinds of change available to allow an animal to live in a new environment are limited to those which are provided naturally by mutations, and therefore it is not possible to perform a major redesign on any part of an animal in one step: only very small changes, each one beneficial in itself, can take place, even if a multitude of such changes can eventually add up to a major change.

Animals, if fortunate, quickly establish a modus vivendi with a new environment; once they have begun to flourish, natural selection tends to constrain them to remain with what works.

Because many of the misconceptions about evolution center around the relationship between evolution and the concept of progress, Dr. Gould has been at pains in his essays to disabuse readers of the notion that progress is a concept that relates directly to evolution. Adaptation to a particular environment, rather than another environment, is indeed not progress in an absolute sense. And mutations are random, much more often noticeably harmful than noticeably helpful, so they are not inherently progressive.

However, the popular mind is right about one thing. Any theory of evolution is a theory of progress. That is, it must be a theory that accounts for the observed phenomenon of progress, however much progress is judged by people in an imperfect and subjective manner.

This is what, in my opinion, Stephen Jay Gould failed to properly recognize as he sought to emphasize the fact - and a genuine and true fact it is - that neither mutations nor natural selection, the driving forces of evolution, have within them any inherent tendency towards progress. Mutations are random; natural selection favors whatever promotes survival in a given environment, which in many cases means changes such as having more fur in a cold climate, or less fur in a warm one, neither of which is "better" in an absolute sense than the other.

The thing is, though, that while those kinds of evolutionary change, being random, will tend to cancel each other out over time, as environments vary in random directions, some small fraction of evolutionary changes will instead be of a progressive character.

Those changes are not always conserved by evolution; one can point to how parasites became simplified over time as an example. The large brains of humans come with a considerable metabolic cost, and thus under conditions of, for example, an extreme shortage of food, evolution could go in the direction of smaller brains. But while progressive changes are not always conserved, they are still somewhat more likely to be conserved than not, while the changes that follow the random variations in local environments are not likely to be conserved over the very long term.

For example, humans, with considerable justification of a kind, consider themselves evolution's most advanced product. But, while we are placental mammals, thus having a higher-energy metabolism than other kinds of creatures, and thus advanced in this sense as a steam engine is over a horse, or a nuclear reactor over a steam engine, primates are considered to be a primitive and generalized type of placental mammal; the ungulates, that is, animals like sheep and cows, are the most advanced and specialized mammals from a more objective perspective.

A human being, or a frog, is a far more complex and intricate item than a 35mm single-lens-reflex camera, or, to use the example given by Paley, a mechanical pocket-watch. A theory that cannot account for complexity and organization in creatures, but which can only account for why some have brown fur and others white, why some have thick, wooly fur, and others sparse, downy fur, would still require another agency to do the hard parts of designing the living creatures on Earth today.

The theory of punctuated equilibria was formed to address the appearance of the fossil record; not to account for progress, as the original theory of evolution by natural selection already did account for progress; those changes we regard as progress, because they are of general application in improving the chances of animals to survive in most environments, by making them stronger or swifter or more clever, would be selected for, at least in animals in certain types of demanding environmental niche. Other changes that we judge as retrogressive, however, are promoted in animals in other situations; animals lose organs they no longer use, so that they need to eat less food to sustain their bodies. Some parasitic animals are good illustrations of this; but even humans are not exempt from degenerative evolution, which is why it is harder for us to live on a meatless diet than it is for mice: we have lost the ability to synthesize some amino acids from others, thus, eight amino acids are essential for us, instead of five.

I can see two possibilities for the relationship between the theory of punctuated equilibria and progress in evolution:

- In the short term, when a small population of animals enters into a changed environment, it makes the "easy" changes that directly relate common genetic variations to the new environment; these include such things as changes in size that show up readily in the fossil record. The more ultimately significant changes are more subtle, and less visible, and they go on continuously, because being stronger, swifter, or more clever is always beneficial;

- Only new environments and small populations create the conditions for evolutionary change; some changes are only specific to the environment, and will be cancelled out the next time the environment is changed in some other direction; but other changes that take place during this time of rapid development will be more generally applicable, and these will be retained, and further built upon, the next time an opportunity for change comes up.

I am quite sure the latter alternative is closer to the truth; but the possibility of the former alternative, if it is not dismissed, will cause objectors to claim that the theory of punctuated equilibria, even if true enough, is irrelevant to "real" evolution. And it is hard to dismiss the first alternative, or even name the alternatives, unless one is willing to talk about progress.

While the objective facts of science, and the processes that do, or do not, happen in nature, are not influenced by human cultural viewpoints, it is our own human attitudes that lead us to decide if a certain scientific theory answers the questions about which we ourselves are curious. When it comes to the development of life, naturally we are more curious about the causes of those changes in living creatures which we subjectively regard as having importance or significance.

What the theory of punctuated equilibria really does for us, therefore, is that it gives us a more accurate picture of how evolution actually works in nature. On the level of individuals, most of the time natural selection works to conserve the characteristics of species and of local populations, exactly as advanced by Edward Blyth. But occasionally, a particular local population will face a change in its environment, and then natural selection will drive change in the members of that population. And most of the time, these changes will simply be direct responses to the characteristics of the new environment, with no inherent value as "progress". But that is most of the time, not always, and given the vast stretches of time over which life has existed on Earth, evolution is still able to account for the vast complexity of advanced life forms despite these factors which make progress the result of only a small fraction of the amount of selection that takes place in nature.