In these pages on the history of the computer, naturally I have only included as participants in that history... real computers that were capable of doing useful work.

But some computers were made on such a small scale as not to be capable of any useful work, in order to serve as aids to teaching or learning about how computers work. And these computers also play a role in the history of the computer.

One of the earliest, and one of the most famous, of these computers is "Simple Simon", a relay-based computer devised by Edmund Callis Berkeley.

Edmund C. Berkeley was famous as the author of Giant Brains, with the subtitle or Machines that Think, a book from 1949 that was perhaps the first popular account of how computers worked. In Profiles of the Future, Arthur C. Clarke was no doubt thinking of this book when he wrote:

When the first large-scale electronic computers appeared some fiftenn years ago, they were promptly nicknamed "Giant Brains" - and the scientific community, as a whole, took a poor view of the designation. But the scientists objected to the wrong word. The electronic computers were not giant brains; they were dwarf brains, and they still are, though they have grown a hundredfold within less than one generation of mankind.

Of course, while Arthur C. Clarke makes a valid enough point here, it is also true that the organization of a digital computer is nothing like that of a brain. Instead, it was organized much like a mechanical adding machine, but with the added features of being able to automatically execute a series of operations, and to store and retrieve intermediate results.

However, we do now have electronic circuits known as neural networks, and artificial intelligence has taken significant strides of late through the use of matrix multiplication performed with the aid of GPUs, so while computers are still far from being much like brains, they are perhaps a bit less like automatic adding machines than they originally were, although as long as they retain what is known as the von Neumann architecture (not that the resemblance to an adding machine is any less applicable to the Harvard architecture, for that matter), not by much.

Later, in 1954, Berkeley would start the magazine Computers and Automation, which had a successful run for over a decade, but then sadly lost most of its advertisers after Dr. Berkeley felt compelled out of a sense of social responsibility to publish articles on a controversial political subject within its pages.

It was his sense of political responsibility that originally led to the birth of the magazine Computers and Automation, as he had left his job to start his own business after it became impossible for him to engage in activities, even on his own time, while holding that job aimed at reducing the danger of nuclear war. So a strong sense of civic responsibility on his part was nothing new.

Unfortunately, though, what caused the decline of the magazine were articles arguing for a conspiracy theory that the CIA was responsible for the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

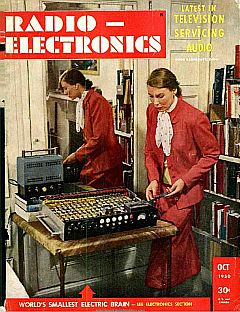

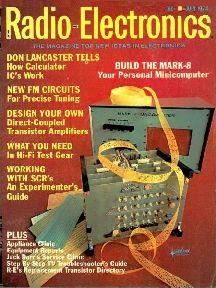

A thirteen-part series of articles, on the topic of how computers worked in general, and on Simple Simon in particular, appeared in the pages of Radio-Electronics magazine, beginning with the October, 1950 issue.

Much later, the July, 1974 issue of the same periodical would anticipate the Altair 8800 by carrying a cover article about the Mark-8, a hobby microcomputer based on the 8008 chip.

The Simple Simon had an internal memory of sixteen registers that were two bits in length, and it executed programs from an input paper tape.

There was also an article about Simple Simon in the November 1950 issue of Scientific American. That article ended with the following prescient paragraph:

Some day we may even have small computers in our homes, drawing their electricity from electric-power lines like refrigerators or radios. These little robots may be slow, but they will think and act tirelessly. They may recall facts for us that we would have trouble remembering. They may calculate accounts and income taxes. Schoolboys with homework may seek their help. They may even run through and list combinations of possibilities that we need to consider in making important decisions. We may find the future full of small mechanical brains working about us.

He passed away on March 7, 1988, so he did live to see the start of the microcomputer revolution that indeed placed small computers that were plugged into wall outlets in our homes.

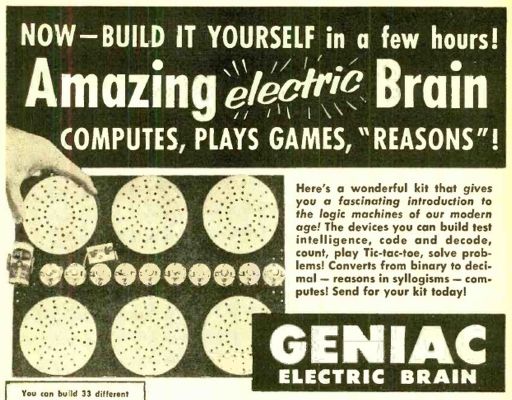

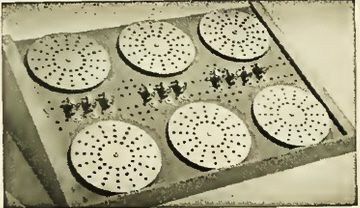

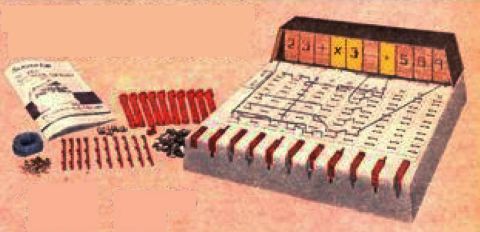

In addition to Simple Simon, Edmund C. Berkely also pioneered a less expensive way of gaining hands-on experience with digital logic. He invented a device called the GENIAC which went on sale in 1955. Part of an early advertisement for the GENIAC is shown at left, and a photograph of the GENIAC from another advertisement is shown at right.

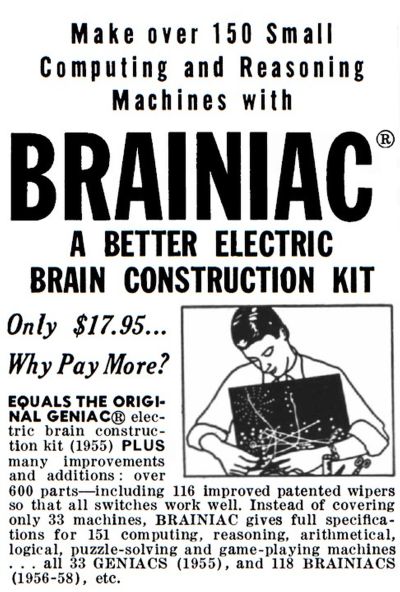

In 1958, he came out with an improved version of the GENIAC with a new name, and this led to another claim to fame for him among comic book fans. Incidentally, this was not the first improved version of the GENIAC; it was preceded by the GENIAC II. Part of an advertisement for this new logic demonstration kit appears at right.

This logic demonstration kit actually preceded the debut appearance of the famous Superman villain in Action Comics 242, its July, 1958 issue. This led to a lawsuit which was settled amicably: no monetary damages were sought, but henceforth, instead of Brainiac being an alien genius from Bryak, he became a computer in human form from the planet Colu instead; this started in Superman 167, the February, 1964 issue.

Superman's first encounter with Brainiac involved him finding and rescuing the bottled city of Kandor.

In Superman 119, the December, 1957 issue, Superman encounters the planet Xenon; it turns out to be an escaped moon of Krypton, with a population of Kryptonians. Superman discovers that it has radioactive elements in its core, meaning that it will ultimately face the same fate as Krypton, but he manages to neutralize them by placing a quantity of Kryptonite deep within the planet. But this means he will never be able to visit the people of Xenon again.

This story could be considered to have been a dry run to test whether or not introducing the bottled city of Kandor later with Brainiac would be popular with readers.

Starting in April 14, 1958, the Superman comic strip in daily newspapers featured another dry run for Brainiac. Superman encounters the villain Romado in outer space, who, like Brainiac, keeps Superman at bay with a force shield; also, like Brainiac, he has a shrunken city from Krypton on his spaceship: Dur El-Va.

Interestingly enough, long before the nature of Brainiac is retconned to make him a computer, Romado, while a living alien being, has a brain that is augmented with computer circuitry. Also, incidentally, at the end of the newspaper story, Dur El-Va is not enlarged on the surface of some planet with a red sun, but instead Superman also takes the bottled city back to Earth with him.

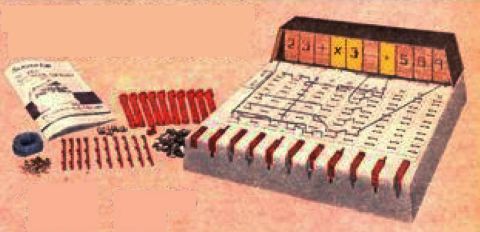

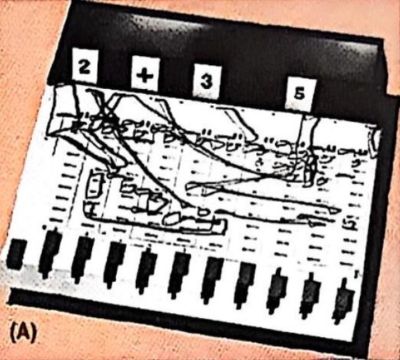

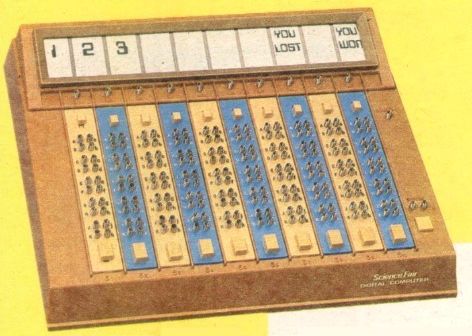

Much later, in the 1970s, devices very similar to the original GENIAC were sold both through Edmund Scientific and Radio Shack. The one from Edmund Scientific is pictured at left, and one from Radio Shack is pictured at right.

A slightly earlier model from Radio Shack, the SF-5000, more closely resembled the one from Edmund Scientific. This apparently was the same product, and it was also sold as the Logix O-600 Electronic Computer. A picture of this version is shown below:

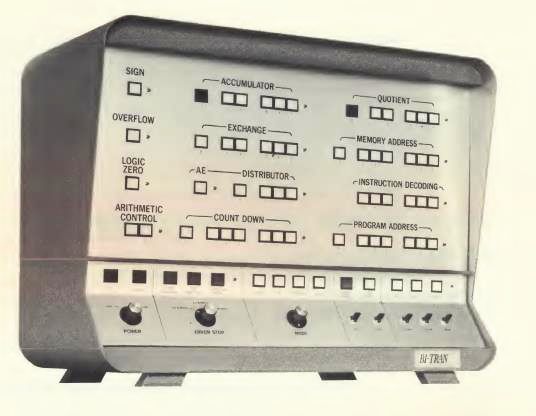

In 1965, Fabri-Tek, best known as a maker of core memories, offered the Bi-Tran Six for sale. Later on, by 1972, it became a product of the Digiac division of Fabri-Tek. This computer trainer had an internal memory of 128 words of six bits each. It sold (at least at one point) for $7,700, which is why, unlike the Kenbak-1 noted below, it tends not to be proposed as a candidate for the title of the "first personal computer".

This device appears in a famous photograph of the first woman to recieve a PhD in Computer Science in the United States, Sister Mary Kenneth Keller. Her degree was recieved from the University of Wisconsin-Madison on the same day in 1965 as the first man recieved a PhD in Computer Science a few hours before, the discipline being a novel one.

They also made another similar machine that was quite different in appearance, the Com-Tran Ten; it was more powerful, having 1,024 words of ten bits each. And, eventually, there was also the Com-Tran 20, which contained Fabri-Tek's MP-12 clone of the PDP-8, and was configured to be useful to teach people how to use that computer.

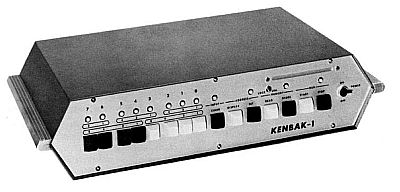

In 1971, the Kenbak-1 was offered for sale at a price of $750, which led some to categorize it as the "first personal computer", even as others had categorized Simple Simon.

It had 256 bytes of shift register memory, and its ALU was bit-serial.