Another line of development involves improving the camera by allowing the photographer to see exactly what the photograph will look like through use of the reflex principle.

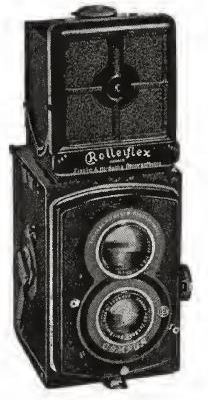

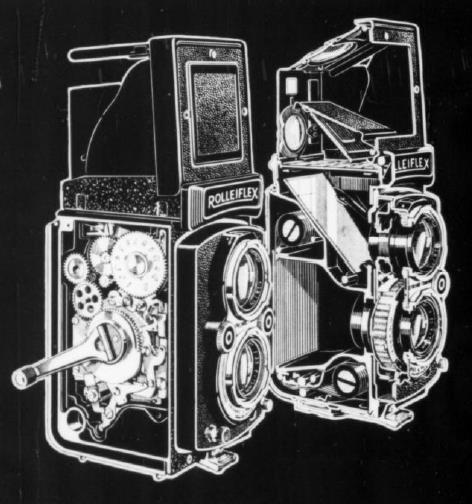

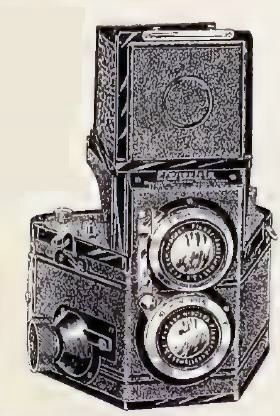

Pictured at right is a Rolleiflex camera, a notable example of a twin-lens reflex camera. The Rolleiflex first came out in 1910, and was widely acclaimed as the best twin-lens camera starting from shortly afterwards; many twin-lens cameras made after its introduction closely resembled it in appearance. For a time, nearly every camera company made a twin-lens reflex camera, as it was for a long time considered by many to be the best type of camera for serious use.

Of the two lenses in the front of the camera, the bottom one was the one that exposed the film; the top one, often of a simpler construction with fewer elements, was used to form the image on a ground-glass plate used in the camera's viewfinder. A mirror at a 45 degree angle allowed that plate to be in the top of the camera. This is illustrated in the diagram of the basic elements of a twin-lens reflex camera at the left.

At left is a smaller image of the same model of camera in which there is a round lens opening at the top of the camera to look through at that image in this photo; often, the shade around the ground glass is simply open at the top instead, but a magnifying lens may be available as an option. A magnifying finder helps with more precise focusing.

Since that image is formed through a different lens, above the one that exposes the film, of course the preview in the viewfinder is not exactly the same as the finished photograph (in addition to being mirror-reversed, although it is right-side up).

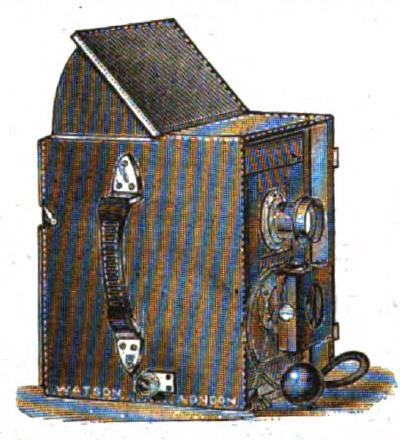

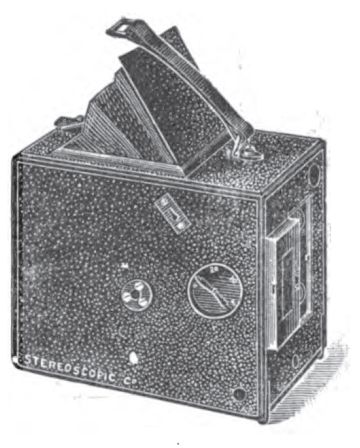

The London Stereographic Company, which also made conventional cameras which were not stereographic, is believed to have made the first twin-lens reflex camera, the "Twin-Lens Carlton" in 1885. At left is shown one of their later models of twin-lens reflex camera, the "Artist", in a later "improved" model.

This image is from an 1897 advertisement, and by that time, several other companies were already making their own twin-lens reflex cameras to compete with this one.

Just two years previously, in 1895, though, there was not an imitator of the twin-lens reflex to be seen, but there were plenty of companies offering single-lens reflex cameras.

Both types of camera required a lens, a mirror, and a means of holding plates or film in a box sealed against stray light. The single-lens reflex also required a mechanism to move the mirror out of the way when taking pictures; the twin-lens reflex required a second lens, but that lens did not need to be of the same quality as the main one, nor did it need an iris diaphragm or a shutter.

As a result, the twin-lens reflex was percieved as being much simpler in construction than a single-lens reflex, adn this outweighed the small disadvantage of a degree of parallax error. Only when single-lens reflex cameras started using 35mm film, which was much smaller than the 120 roll film typically used in both twin-lens reflex and single-lens reflex cameras previously, so that the 35mm single-lens reflex could have a pentaprism added, thus making looking threw the viewfinder of a 35mm SLR as simple as looking through the viewfinder of a simple viewfinder camera or a rangefinder camera, did the popularity of the SLR begin to skyrocket. Until then, the twin-lens reflex essentially reigned unchallenged, although the single-lens reflex also maintained a definite presence, as its advantages did give it a secure niche.

On the left is shown an image of the original Twin-Lens Carlton as it appeared in an advertisement; the door that opens to allow the two lenses to be used is clearly visible in the image, but the two lenses are not.

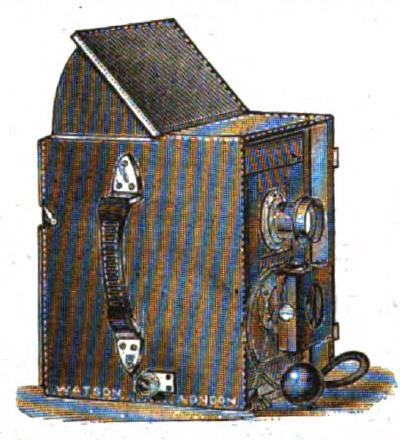

Below, we see two of the competing twin-lens reflexes that seem to have sprung up in 1897, the Watson Double Camera and the Butcher Primus.

|

|

In order for a twin-lens reflex camera to have its box-like shape, the film usually has to follow an unusual path; it will travel vertically in the camera, with one reel lying under the reflex mirror in the top chamber, and the other reel being in the front of the camera on the bottom, so as to be nestled under the lens opening, where it won't block the camera's view. This is illustrated in the diagram at left, and in the illustration from a Rolleiflex advertisement shown at right.

The Planovista twin-lens reflex camera, illustrated on the left, eschews such complexities. Instead, it has a strictly utilitarian shape that discloses what is going on inside the camera. The top chamber's back slopes to follow the reflex mirror; the bottom chamber is shaped like a conventional camera, to provide room for the film reels on the right and the left.

Incidentally, when I attempted to look online for more information about the Planovista camera, I obtained results stating that Planovista was another name under which the Primarette camera was sold - and this camera is of a completely different design to that of the version of the Planovista for which I obtained an image. An image of the Primarette, the best I could find that I could use for now, is shown at right; two of them are in the picture, the one on the left being opened for taking pictures, and the one on the right being closed.

The Primarette, made by the French company Bentzin, was almost a twin-lens reflex camera, but not quite. That's because there was no reflex mirror; the ground glass screen on which the image from the top viewing lens was viewed simply was directly behind the viewing lens, in the same orientation as the film was behind the other lens, as in a view camera. This meant the user of the camera saw an upside-down image, which led to that camera not being a success in the market.

The camera had a bellows between the back with the film and the front with the lenses, and the absence of a reflex mirror meant that when the camera was closed, it was almost flat. It was this level of portability that was the camera's main feature.

Kodak's Brownie Hawkeye camera, shown at left, which was very popular because it sold at a low price, was a viewfinder camera, not a twin-lens reflex. Because of that, the viewfinder image was bright enough that no shade was needed.

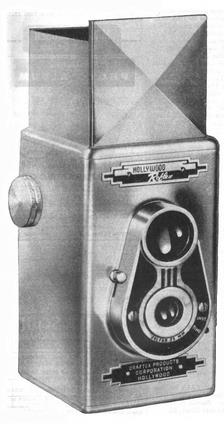

This was despite the fact that it was pointed in the right direction by looking down at it; I can't really describe it as having waist-level focusing, since the lens was always focused at infinity, not being adjustable in this manner (as was the case for many inexpensive cameras). In fact, out of fairness to the Brownie, at right I show an image of the Hollywood twin-lens reflex, which was an inexpensive twin-lens reflex the lenses of which were fixed-focus.

The Brownie Hawkeye used Kodak 620 film. The film was basically identical to Kodak 120 film, but it was wound on a smaller spool so as to allow cameras using it to be more compact.

The Kodak Brownie Hawkeye wasn't intended to look like a twin-lens reflex camera, even if it did have a slight similarity to one. The same can't be said for the Kodak Duaflex II camera, a viewfinder camera shown at left, unfortunately.

However, the Kodak Duaflex was far from alone; another example is the Argus Seventy-Five, shown at right.

Kodak did make an actual twin-lens reflex camera of its own for a while, simply called the Kodak Reflex. Announced in 1946, advertisements for it in 1947 still referred to it as "on the way".

This camera also used 620 roll film, but Kodak made available a conversion kit for it to allow it to use 828 film. This was a small format of roll film, with a paper backing like 620 film or 127 film, but 35mm wide. While this film didn't have the prominent sprocket holes of 35mm cine film, it did, at least originally, have one sprocket hole every 43.5 mm, for its standard frame size of 28mm by 40mm.

Some European brands of twin-lens reflex camera offered masks and spool adapters to allow those cameras to use different types of film as well; I presume this has something to do with the popularity of this type of camera, leading people to want to use their camera of this type, rather than a rangefinder or viewfinder camera, even if changing to a different type of film. And this makes sense: the single-lens reflex camera, after all, was hugely popular because it let you see the exact picture you were taking; the twin-lens reflex may have fallen slightly short of that goal due to parallax error, but it still came closer to it than other common camera types.

Unlike the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye, the Bolsey C camera, seen at right, actually was a 35mm twin-lens reflex camera despite not looking like one. But not only did it have a compact and slim form which caused it to resemble a rangefinder camera, it also in fact included a rangefinder, just like the Praktina FX which we will see later, which was an SLR that also had a rangefinder.

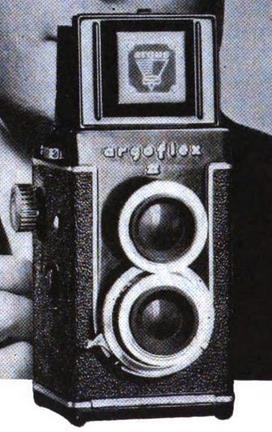

Argus, which, as we have seen, was a company that competed very aggressively with Kodak on price and features, also made a twin-lens reflex camera. Shown at right is the Argoflex II, which improved on the original model by having the aperture of the viewing lens increased to f/3.5 in order to make the scene on the focusing screen brighter.

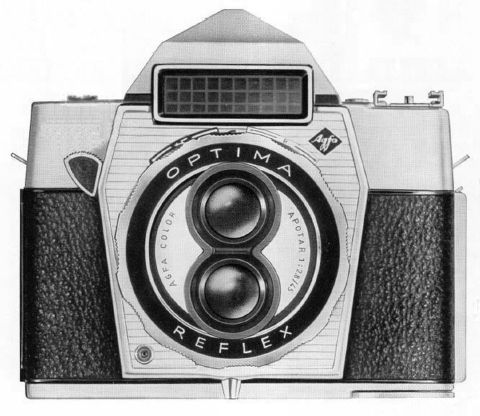

And then there was the Agfa Optima Reflex. It was preceded by a similar camera, the Agfa Flexilette, which did not have the selenium exposure meter, and which also had a waist-level finder instead of a pentaprism. This camera was a twin-lens reflex using 35mm film which was clearly inspired by the appearance of 35mm single-lens reflex cameras, and it continued to be available for several years after its 1961 debut.

The Agfa Optima Reflex, like the original Agfa Optima from 1959, put the aperture and the shutter speed under the control of the camera's selenium cell light meter, and so again this camera offered an automatic exposure system preceding that of the Konica Autoreflex T, and this time in a camera with a reflex viewfinder as well. So it has that going for it.

|

The image above is from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is Ashley Pomeroy. |

Although my initial reaction to the Agfa Optima Reflex was to wonder what they could have been thinking in order to introduce such a camera to the market, I have read a comment on it which noted that because the vertical parallax was quite small, since it used 35mm film, and since it had a straight-through pentaprism finder, and yet the mirror didn't block the view when taking pictures, this camera embodied the best of both SLR cameras and TLR cameras.

Well, I disagreed with that argment on one point: the Agfa Optima Reflex did not have interchangeable lenses, which, to my mind, are the most significant feature of the typical 35mm SLR camera.

However, it is not impossible to make a twin-lens reflex camera with interchangeable lenses, and this was in fact done at least once: the Mamiyaflex C series of cameras offered that feature. The Mamiya C33 is shown at right; note that its finder is also interchangeable.

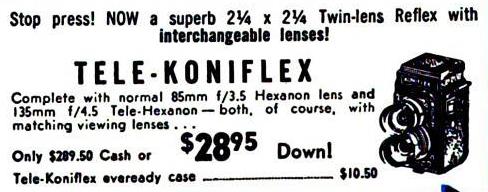

The Mamiyaflex C series of cameras are the best known twin-lens reflex cameras to have interchangeable lenses, but there were others. According to one website I encountered, Konica briefly made the Koni-Omegaflex starting in 1968 which had this feature. And apparently this wasn't the first time for Konica, as I stumbled upon this mention of the Tele-Koniflex in an advertisement from 1956 shown at left.

The Koni-Omegaflex looked like a normal twin-lens reflex camera; but it was part of a series of cameras that included other cameras of different types. Shown at right is the Koni-Omega Rapid M, which was a rangefinder camera. It was advertised as facilitating taking pictures quickly, and was categorized as a press camera.

Also, the original Contaflex camera from 1935 was in the category of twin-lens reflex cameras with interchangeable lenses.

The Contaflex twin-lens reflex from 1935 also used 35mm film, rather than, say, 120 roll film like a typical TLR. Advertisements for it indicated that there were initially six lenses available for it; I have found an early manual online which lists seven lenses for it, on a web site which indicated that eight lenses were known to have been available over its lifetime:

35mm f/3.5 Orthometar (#8, not in the manual) 35mm f/2.8 Biogon 50mm f/2.8 Tessar 50mm f/2 Sonnar 50mm f/1.5 Sonnar 85mm f/4 Triotar 85mm f/2 Sonnar 135mm f/4 Sonnar

Only the lens which exposed the film was interchangeable; the one for the reflex viewfinder remained in place. Thus, the viefinder screen had markings indicating the narrower field of view of an 85mm lens and of a 135mm lens. This is a scheme that is commonly in use in home movie cameras, although they don't usually omit the field of view of the wide-angle lens.

Another unusual design feature of the Contaflex was that the upper reflex chamber was on a larger scale than the lower part which exposed the film. In order to achieve a larger and brighter view in the viewfinder, the viewing lens had a focal length of 80mm rather than 50mm, and the ground glass for viewing was larger than the 24mm by 36mm exposure area of the film in the same ratio. Of course, making the viewing area larger particularly helped when focusing with an 85mm portrait lens or a 135mm telephoto lens in use.

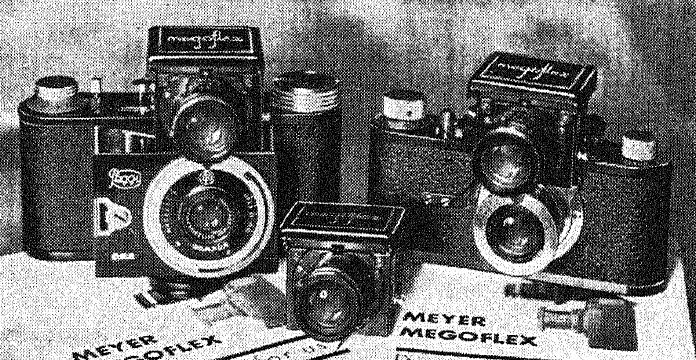

And, speaking of unusual 35mm TLR designs: in 1952, a Japanese company, Arco Photo Industry, not only made the Arco 35 rangefinder camera, but in the shoe (where one normally puts flash equipment) one could put the View-Arco which was basically the top half of a TLR, to give reflex viewing to this camera. Another company, De Mornay-Budd, made a similar attachment which their advertisements noted could be used for the Leica or the Contax, and there was also the Megoflex for the Contax I.

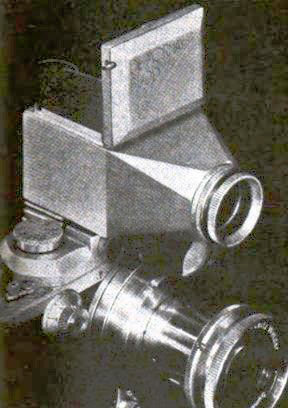

I was able to find an advertisement for the De Mornay-Budd Reflex View Finder with a picture of the device, which is shown at left.

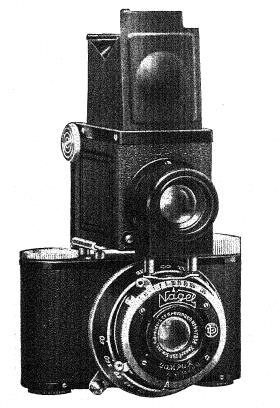

It turns out, though, that this was not an entirely novel idea. Shown at right is an image of the Nagel Rolloroy reflex attachment, which dates back to the early 1930s!

And we've already heard of Nagel, the company that made it, on a previous page, this being the company that Kodak bought so that it could offer the Retina line of cameras, which was introduced with the 135 film cartridge.

It turns out that the Megoflex was also from the early 1930s; and an advertisement for it noted it could be used with the Leica, the Contax, and another camera called the Peggy. It is pictured below: