Originally, this page had not attempted to be a complete history of photography, from the daguerrotype to the digital camera of today. Instead, it looked at a few types of camera in order to explore one particular line of development within the history of film cameras. However, some brief coverage of other material has now been added.

The story begins on this page, but will continue on other pages, as otherwise the page would be slow to load, having too many images.

Most of these pages deal with the 35mm single-lens reflex camera, with additional pages dealing with camera types that preceded it and contributed to its development, but as well, as noted, a limited more general coverage has been included.

Also, a special effort has been made to include a mention of camera models which in some way were unique or unusual. Examples of this include the Contax RTS III, which had a vacuum back to enable the sharpest possible focus, and the Ricoh TLS 401, which used mirrors instead of a pentaprism so that it could also have a knob to flip one of the mirrors out of the way for waist-level viewing.

The camera obscura had been known since mediaeval times. Light-sensitive chemicals were known in the early modern era, but a way to record the current state of light-sensitive chemicals in substances not sensitive to light took many more years to find.

Niecephore Niépce was the first to develop a working photographic process, but it was so insensitive to light as not to be practical.

Louis Daguerre invented the Daguerrotype; he was rewarded for his invention by the French government, which made it freely available. It produced photographs as direct positives on a metal surface, and so these photographs could not be copied as other Daguerrotype photographs, even if, since they could be seen, later, more advanced methods of photography could capture them, allowing them to be reproduced in books.

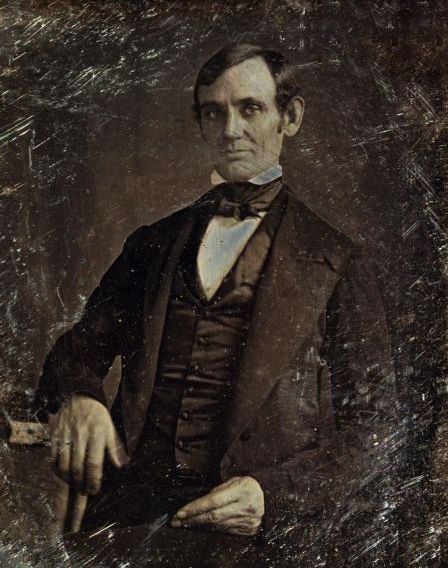

The early photograph of Abraham Lincoln shown at left is a Daguerrotype.

Fox Talbot invented the calotype. This involved a negative, but the negative was on paper rather than on glass or clear plastic film, meaning a great deal of light was required to create the final print. As he sought high royalties for the use of his process, it was not popular; worse yet, he claimed that the wet plate collodion process was derived from his invention, and thus also subject to those royalties, holding back the progress of photography in Britain until some individuals bore the cost of defeating him in court.

Frederick Scott Archer published the wet plate collodion process in 1851. This process produced clear black-and-white photographs which fully stand up to comparison with photographs made by more modern means, but it still had one serious limitation; the photographer had to prepare the plate, take the picture, and then develop the plate all within the space of a few minutes. So photographers had to bring their darkrooms with them, not just their cameras.

One famous photographer who made use of the wet plate process was Mathew Brady, who made many photographs documenting the Civil War in the United States.

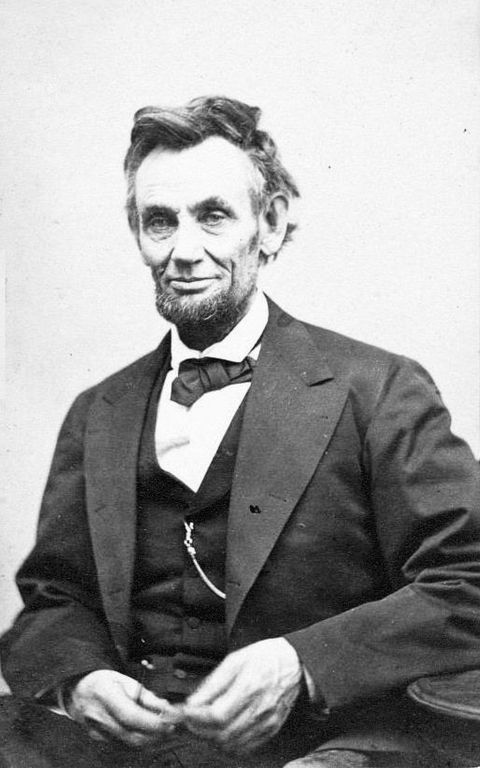

The later photograph of Abraham Lincoln, taken by Alexander Gardner, shown at right was made using the wet plate process.

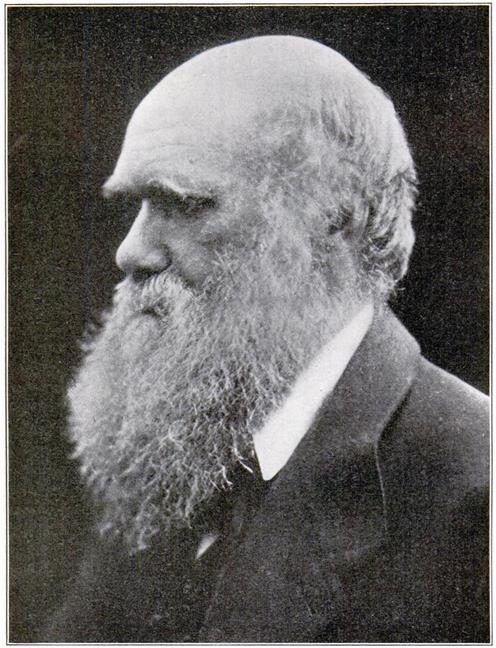

Another example of a photograph made using the wet plate process is the famous portrait of Charles Darwin by Julia Margaret Cameron, shown at left from a halftone reproduction.

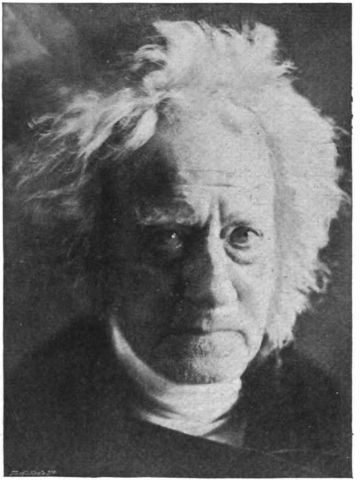

Another photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, shown at right, is this one of Sir John Herschel, discoverer of the planet Neptune by means of calculations of the perturbations of the orbit of Uranus caused by its gravitational attraction.

The limitation of the wet plate process referred to above, that photographers had to take their darkrooms with them, is illustrated by the photograph shown below (which I have cropped) of the equipment Mathew Brady took with him as it was outside Petersburg, Virginia in 1864.

Early attempts at dry plates led to reducing their sensitivity to light, and were therefore impractical.

The gelatin dry plate, invented by Richard L. Maddox, first available to the public in 1873, finally ushered in the "modern" era of photography, where plates could be manufactured and sold, photographers just brought their cameras with them, and then developed the plates at their leisure, or even had someone else do it. However, others also contributed significant improvements to the gelatin dry plate after him; Charles Harper Bennett, later in 1873, found a way to significantly increase the sensitivity of gelatin dry plates through heating them, and in 1879, George Eastman developed a way to coat gelatin dry plates with a machine, thus significantly improving the economy of their manufacture.

George Eastman's first roll film, from 1885, put a gelatin emulsion on paper for taking pictures, but transferred the emulsion to clear plastic in processing. Roll film was invented by one Hannibal Goodwin, working at Anthony and Scovill... which later became Ansco. Eventually, Eastman Kodak would be sued for patent infringement; the amount obtained saved Ansco from immediate bankruptcy, but it still ended up as a distributor for Agfa films instead of a producer of film stock in its own right.

Transparent plastic roll film followed in 1889; this was changed from flammable cellulose nitrate to the safer celluose acetate starting in 1908.

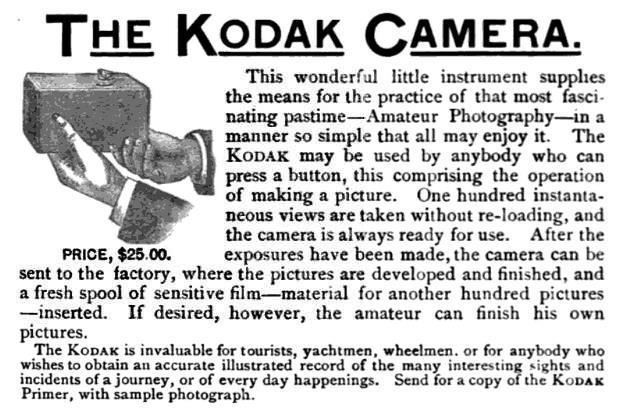

The original Kodak camera, the one that came with enough film for 100 exposures, and had to be sent in for processing, and yielded round pictures, was from 1888, so it used the original paper film. Here is an early advertisement for it:

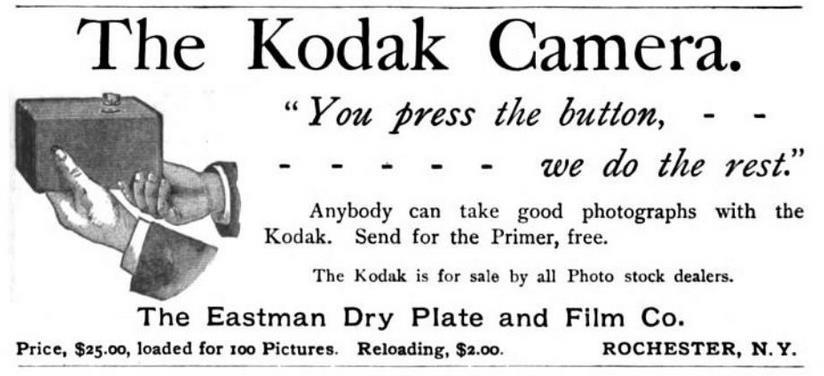

And here's another advertisement for the original Kodak from the following year, bearing what was perhaps their most famous slogan:

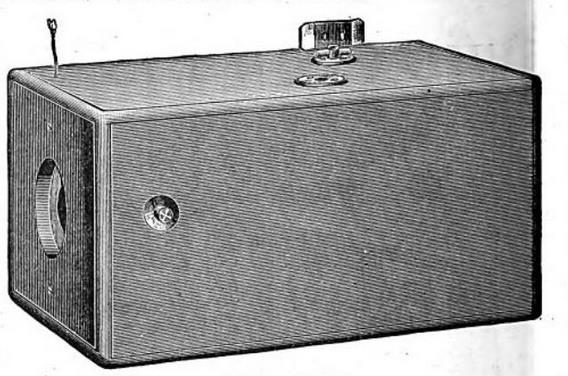

Shown at right is an example, from the Kodak Primer, of the sort of photographs this camera took, and at left is an illustration of the appearance of the camera itself from an early advertisement.

To start off, the image at right is of an Ermanox camera. This was made by Zeiss, and it used glass plates. One could get an f/1.8 Ernostar lens for it, which was an incredibly wide aperture for the time.

The image at right, however, is of an Ermanox with an f/2 lens, from an advertisement at a time when this was the fastest lens available for the camera. The photograph of the camera in the advertisement was even credited, to the photographer Anton Bruehl. (For this page, though, it has been cropped to just show the camera itself.)

This was the camera that Erich Salomon used for his famous work in available-light photography.

|

|

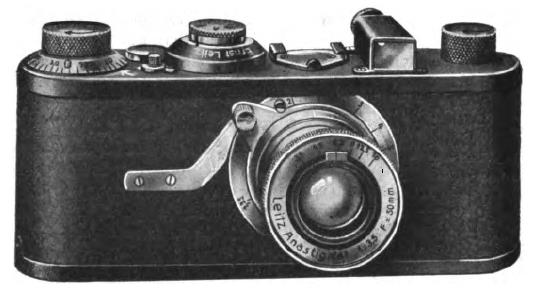

The Leica, pictured at right, originated the 36mm by 24mm image format for 35mm film. It was used for candid photography by a number of famous photographers, and thus, it seems to me, it could be viewed as the spiritual successor to the Ermanox. Two images are shown at right; the top one is of the Leica as it was when originally introduced in 1925; the second is of a later version, the Leica IIIg, dating from 1957.

Some people have criticized the 3:2 aspect ratio of 35mm still photographs as too wide, preferring the 7:6 aspect ratio of some medium-format cameras, for example. Had the designers of the Leica chosen to advance the film by seven performations instead of eight after each photograph, as the spacing between perforations was 4.75 mm, this would have been sufficient to accomodate a 32mm by 24mm image format, with 1.25 mm of spacing between images, giving the same 4:3 aspect ratio as 35mm film gave for motion pictures. If, indeed, this would have been preferable, how much film stock would have been saved had that been done!

Later on, we will see that Nikon actually attempted to change over to that format in their first 35mm rangefinder camera, and this attempt nearly caused the company to fail before it got started exporting their products outside Japan.

In fact, if six, rather than seven or eight, perforations were used for a picture, that would have allowed a 24mm by 28mm image format, providing the desired 7:6 aspect ratio, but with only 0.5mm between successive images. The distance between successive 18mm by 24mm frames in 35mm movie film was 1mm, and the distance between successive 24mm by 36mm film is twice as much, 2mm, so that would likely not have been enough, and instead a 24mm by 27mm frame, for a 9:8 aspect ratio would be the widest possible for a six-perf format.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a famous photographer who was an early user of the Leica.

Incidentally, the official standard for 35mm film specifies that its width should be 34.976mm wide, plus or minus 0.025mm, which means that 35.001mm is the maximum width allowed. When this type of film was originally devised by Thomas A. Edison, however, its nominal width was 1 3/8 inches, which is now a thousandth of an inch narrower than the minimum width allowed by the standard, 1 3/8 inches being 34.925 mm.

|

The image above is from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.0 Generic License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is Joe Haupt. |

In what follows, I will be shamelessly neglecting another major branch of photography. These pages concentrate on the 35mm SLR, while also briefly touching on cameras with other film formats, as well as some digital cameras. The sprocketed film that the 35mm camera makes use of, as already mentioned above, already existed since it was used for another purpose: motion pictures.

And so if I am going to mention still-picture cameras of various kinds, should I not also mention motion picture cameras? But except for one mention of Polavision, motion picture cameras are completely ignored in the following pages. So, here on this first page, I will mention a very few such cameras. Depicted at left is the Brownie 8mm camera from Kodak, and at right the Holiday II 8mm camera from Mansfield.

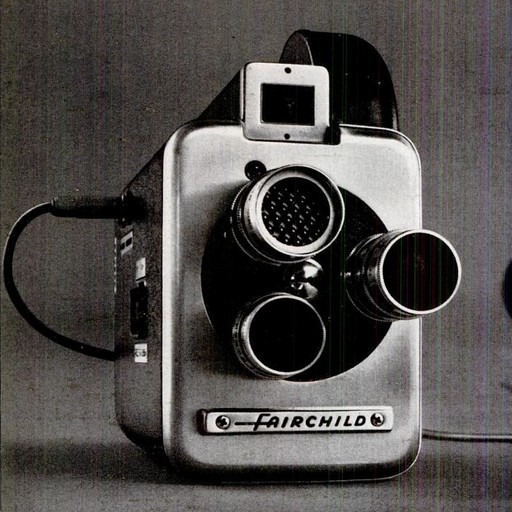

And here, at left, is the Fairchild Cinephonic, first introduced in 1960, an 8mm camera for home use that actually recorded sound on the film. However, it did not use ordinary standard 8mm film, as it recorded the sound magnetically, so the film had to have a magnetic stripe.

Instead of just mentioning a few random home movie cameras, though, I should get a bit more systematic. As far back as 1899, a 17.5mm film format was introduced to make film-making more economical for amateur movie-makers. This was a British invention, by one Alfred Darling, the Biokam, but soon after, in 1903, the Ernemann Kino used a very similar 17.5 mm film format as well. An engraving of the Biokam from an advertisement is shown at left; the unit actually combined a camera, a projector, and a device for developing the film in a single unit. These film formats made use of a central perforation similar to that of 9.5 mm film. Actually, in 1898 another 17.5 mm film format had been introduced with a format very similar to that of modern 16 mm film for the Birtac by Birt Acres.

Pathé introduced 9.5 mm film in 1922, at first for home projection of 9.5 mm prints they sold, but soon after, they sold 9.5 mm movie cameras for personal use. One of their cameras, not the first model, is shown at right.However, some sources claim that the Ciné-Kodak Model B was the first successful home movie camera, introduced in 1925 (with the Model A having been introduced in 1923). These cameras used 16mm film. An image of this camera, in a detail from an advertisement, is shown below.

Despite the acute accent, this was a camera sold by Kodak in the United States, not an effort by their French subsidiary.

Shown at right is the Ciné-Kodak Eight. This camera was introduced in 1932, marking the introduction by Kodak of 8mm film to make home cinematography more affordable.

This photograph from an advertisement shows two early Kodak Super 8 cameras, the Kodak Instamatic M4 on the left and the Kodak Instamatic M6, which had the additional feature of a zoom lens, on the right.

The Super 8 movie film format was introduced in April 1965, which improved the image quality of home movies by allowing a somewhat larger area of film for each image in a movie. The image at right compares several home movie formats; first, the 9.5 mm format from Pathé, then Kodak's original standard 8mm home movie film, followed by Super 8, and then a proposed improvement of 8mm from one M. Garcin in 1945.