It did not take long for a very large number of camera companies to bring out their own 35mm SLR cameras, as the pentaprism, allowing the image to be previewed conveniently by looking forward just as with an ordinary camera viefinder, made this type of camera much more convenient to use.

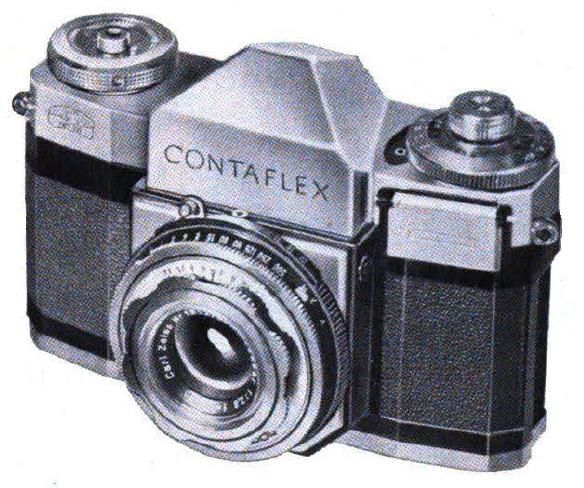

Pictured at right is the Contaflex, from the West German piece of Zeiss, Zeiss Ikon.

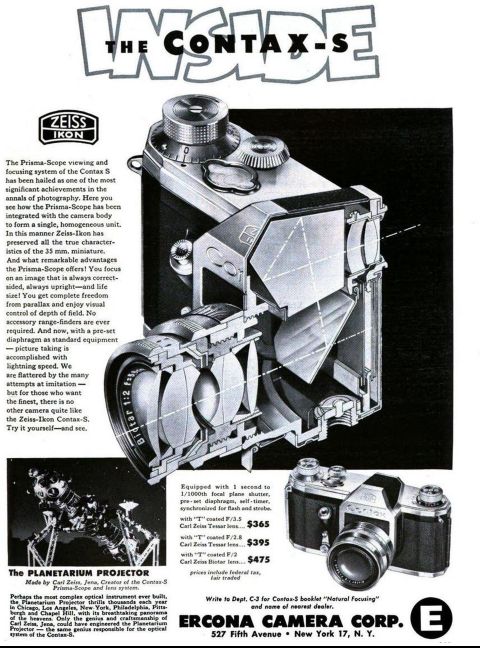

Apparently even before the Contaflex, Zeiss Ikon was selling SLRs with pentaprisms, under the Contax-S name, as I have seen advertisements for them in old photography magazines. In the meantime, as the East German firm lost the rights to certain classic camera names in the West, the Contax-D was sold as the Pentacon in the West, and so on. Zeiss Ikon, instead of making their own Contax-S, was acting as the importer for the original Contax-S made by Carl Zeiss Jena in East Germany; although the camera bears Zeiss Ikon branding, the advertisement for it shown at left explicitly credits the East German firm of Carl Zeiss Jena for its design and construction, giving a planetarium projector of theirs as an illustration of that firm's abilities.

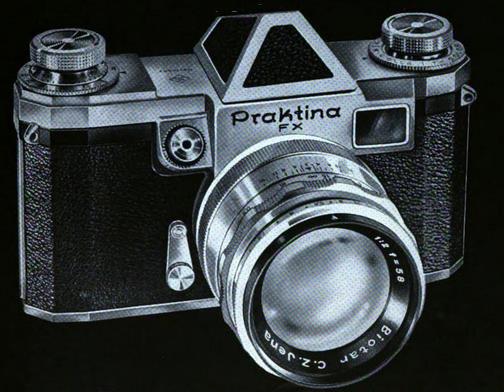

In 1956, the same year that the Praktica fx-2 came out, another East German firm brought out the Praktina FX. This was their top-of-the-line camera; like the fx-2, its pentaprism was removable. But instead of using a screw mount for its lenses, it introduced a bayonet mount, as many other camera makers would eventually do. But its most unique feature is that although it was an SLR, it also had a rangefinder built into the camera body, similar to those found in rangefinder cameras. This allowed it to be used as if it was a rangefinder camera, thus making it effectively two cameras in one, except, of course, for not being as light as a rangefinder camera.

Incidentally, the Praktina FX was a product of the East German firm of Kamera Werkstätten Guthe & Thorsch, not of Pentacon, the makers of the Praktica cameras.

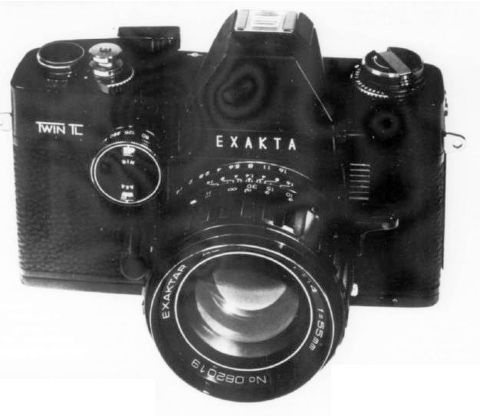

The camera shown at left was billed the Exakta-West Twin TL in a 1973 advertisement. And indeed the company selling it was the West German remnant of Ihagee, it having also survived as two separate firms even as Zeiss did.

This camera was made for the West German Ihagee by Cosina in Japan, however. It had a through-the-lens cadmium sulfide meter, and one could order the camera with either a 50mm f/1.8 lens or a 55mm f/1.4 lens. And one could use both Exakta bayonet-mount lenses with it and screw-mount lenses!

Maybe the West German Ihagee made and sold cameras in Germany all along, but as I'm not aware of any Exakta cameras offered for sale in the United States before 1973 from anywhere but East Germany, I suspect very few people seeing this advertisement were prepared to entertain the possibility that this camera came from anywhere else, and so I expect it sold poorly and vanished into obscurity. But I could be wrong. If that was the case, though, then the moral of the story is the importance of maintaining brand visibility.

A web search turned up more information. Johan Steenburgen, who originally founded Ihagee in 1912, managed to find himself in West Germany after World War II, and he founded the western version of Ihagee in West Berlin. It did make one other camera for the German market in 1966, the Exakta Real.

Oh, and the Exakta Real used a modified version of the Exakta bayonet mount to allow the camera to have more advanced features. Which inspires one to ask which Exakta bayonet mount did the Exakta Twin TL support in addition to the popular screw mount?

The company ceased operations in 1976, and so indeed the posession of a storied name turned out to be a great hindrance rather than an asset, because the East German version of the company was far more well-known, having been a constant presence, if not necessarily a terribly well-respected one, in the camera market for years.

Had they realized the seriousness of the issue, they could have had run ads for the Twin TL that started something like this: "You've heard our name. But you've probably never heard of us", followed by an explanation that yes, we really are a West German company, and then start talking about the camera. Just saying it's from Exakta-West is not enough to convince people that this isn't just a labelling trick by the East German company or one of its importers.

Even Eastman Kodak offered an SLR, the Retina Reflex, starting in 1957. A picture of this camera, from an advertisement, is shown at right. The most distinctive feature of Kodak's Retina Reflex cameras is that they had a conventional shutter, located on the body immediately behind the lens, rather than the focal plane shutter usually found on single-lens reflex cameras.

While this seems to be a highly unusual design decision, it was not a unique one. In fact, this was also true of most of the Contaflex line of cameras, the first of which was just mentioned above.

Focal-plane shutters achieve high effective shutter speeds by allowing only a small part of the film to be exposed at any one time as the shutter moves across the film area. This leads to two major drawbacks. One is that the shutter is limited to flash synchronization speeds slow enough to allow the entire exposure area of the film to be open to incoming light at the same time; this could be as fast as 1/125 second with a fast metal vertical focal plane shutter. The other is that at fast shutter speeds, fast-moving objects will have their shapes distorted.

A leaf shutter in the lens, on the other hand, can synchronize with flash at any speed at which it can operate, and does not create artifacts of shape distortion because the whole film is exposed, or not, all at once.

Thus, while focal-plane shutters were far more common in SLRs, there is still a list of several SLRs with the other type of shutter instead: The Contaflex, the Voigtländer Bessamatic and Ultramatic, the Alps Ambiflex, some early Topcon cameras, and the Kowa SER, SETR, and SETR2.

The Achilles heel of this type of camera, however, has tended to be that the variety of lenses available for any particular camera of this type has tended to be limited. One contributing factor is that sometimes some optical elements of the lens are behind the shutter on the camera body, making only the front part of the lens interchangeable, in order to more closely approximate the ideal position of the shutter within the lens. However, some of the manufacturers of this kind of camera made an effort to avoid this pitfall.

Also, other camera makers that chose to use focal-plane shutters still sought to make the benefits of leaf shutters available to their customers by making available for their cameras a limited number of lenses with built-in leaf shutters that could be used while the focal-plane shutter was left open, as for a time exposure.

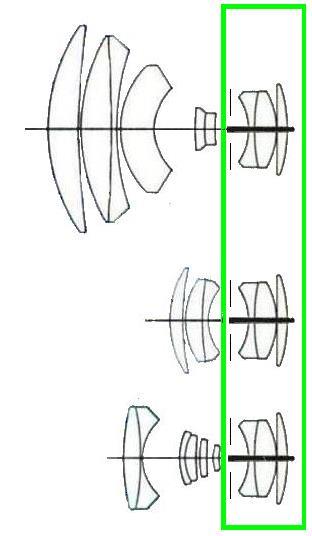

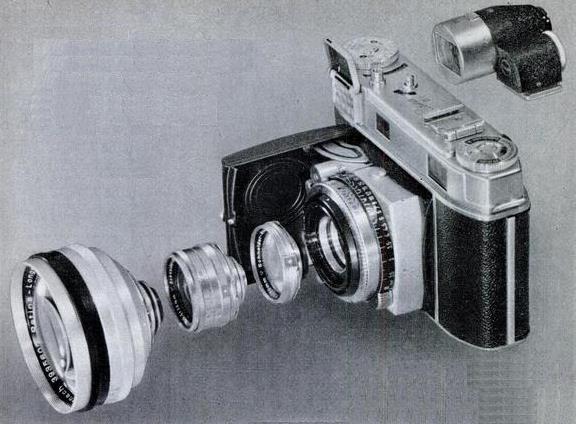

The camera came with a 50mm lens of the Double-Gauss type. The rear half of that lens, along with the diaphragm and the shutter, were fixed to the camera. The front half of the lens was interchangeable, allowing the focal length to be changed to 35mm or 80mm.

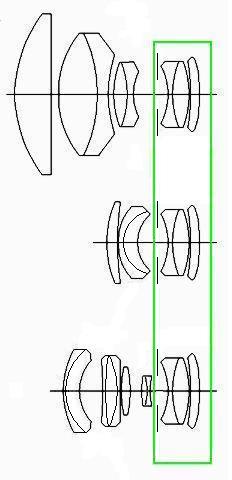

The original Kodak Retina Reflex used the same lenses as the Kodak Retina IIIc rangefinder camera. At left is an image, from a Kodak advertisement, of an exploded view of the Kodak Retina IIIc camera, together with the front components of the Schneider version of its compound lens, and also an auxilliary viewfinder, as the rangefinder Retina IIIc, unlike the Retina Reflex, would require for interchangeable lenses - or, in this case, for interchangeable front components of a compound lens - having different focal lengths.

|

|

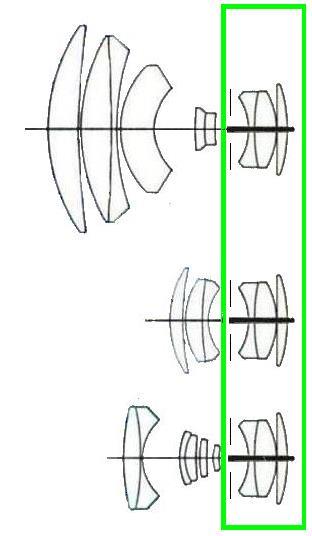

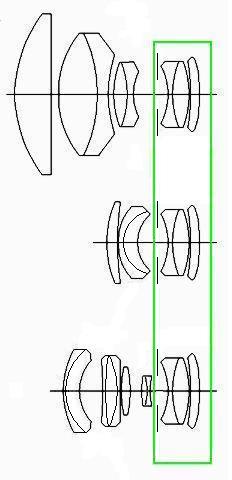

The two diagrams at right both illustrate how the system of compound lenses shared by these two cameras works. The aperture stop is shown in each lens diagram, but not the shutter; the shutter, the aperture stop, and the lens elements to the right of the aperture stop are what is the same in each of the three cases shown, and are fixed to the camera: the diagram shows the part that remains the same within a green rectangle.

The leftmost of those two diagrams shows, in order from top to bottom, diagrams for the telephoto (or portrait) lens, the 80mm f/4 Longar Xenon, the 50mm f/2 Xenon, and the 35mm f/5.6 Curtar Xenon. This is the set of lenses made for the camera by Schneider; some Retina IIIc cameras and some Retina Reflex cameras used Rodenstock lenses instead; as their lens set was different in design, it was necessary to use the correct front components for the camera that you had.

The Kodak Retina Reflex and its rangefinder predecessor, the Kodak Reflex IIIc, were not the only cameras to use this general type of convertible lens system. A very similar system was offered by Zeiss Ikon with their Contaflex III camera from 1957.

There were three subsequent models of the Kodak Retina Reflex, the Retina Reflex S, the Retina Reflex III, and the Retina Reflex IV. These cameras placed the leaf shutter inside the camera body, and had conventional interchangeable lenses using the DKL mount. Although other manufacturers also used this mount, some of what I have read suggests that there were variations in the mount between manufacturers, so that DKL mount lenses weren't interchangeable between camera brands.

I have finally been able to find an image which gave me a glimpse of the Rodenstock Heligon lenses for the Retina Reflex camera, and based on it, I have drawn the additional diagram shown at the furthest right of that version of the lenses. It may not be entirely accurate, as the image I had found did not show the relationship between the two portions of the compound lens, or the position of the stop, so some guesswork is present in this diagram. Initially, I had omitted some cemented surfaces; it is possible now that I have erred in the opposite direction.

Since a compound lens is one way of providing multiple different focal lengths without requiring the purchase of a complete lens in each of those focal lengths, one could think of a compound lens system as being, in one way, an alternative to a Zoom lens, which achieves that end in a different way (and to a different extent).

If one looks at these two types of lens from that perspective, then a third alternative would be a single lens which, unlike a Zoom lens, does not have a continuously variable focal length, but which instead can be switched between two (or more) discrete focal lengths.

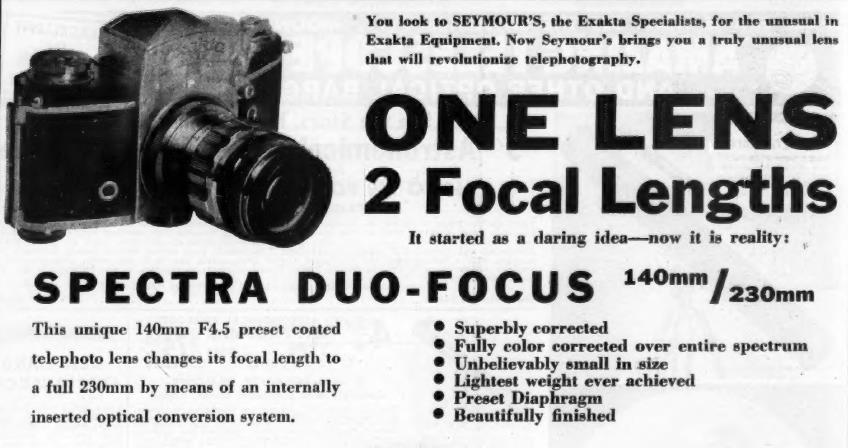

This third theoretically possible alternative was actually tried at least once, as the 1959 advertisement shown above, for the Spectra Duo-Focus lens from Seymour's, a retailer for Exacta cameras and accessories, illustrates. This lens could switch between focal lengths of 140mm and 230mm.

Of course, in contradiction to the text of the advertisement, this lens did not "revolutionize telephotography", but instead was quickly forgotten and languished in obscurity.

There is, of course, also a fourth alternative, which was very commonly used, that isn't covered here: one could place a teleconverter, or, for that matter, a focal reducer, behind the lens, or an auxilliary lens in front of the lens on a camera to change its focal length. The first alternative is only applicable to cameras with interchangeable lenses, but the second provides a way to obtain different focal lengths on a camera with a single lens fixed to the camera body.

The firm of Eastman Kodak, known for the wide selection of cameras it made along with its films, was not the only firm best known as a producer of film stocks that felt the need to offer an SLR under its brand.

Fujifilm is well known for its digital SLR and mirrorless cameras today, and they did also make a number of film cameras as well.

Also, Agfa, the German film producer behind the infamous Agfa Optima Reflex camera featured earlier, didn't only make a twin-lens reflex camera that sort of looked like an SLR; they also sold real SLR cameras, such as the Agfaflex IV, pictured at left.

This camera also used a leaf shutter, attached to the body of the camera behind the interchangeable lens. The Agfaflex III was a version of this camera with a waist-level finder instead of a pentaprism, and the Agfaflex I and II were models with a fixed lens instead of interchangeable lenses; they weren't successive models in the same line.

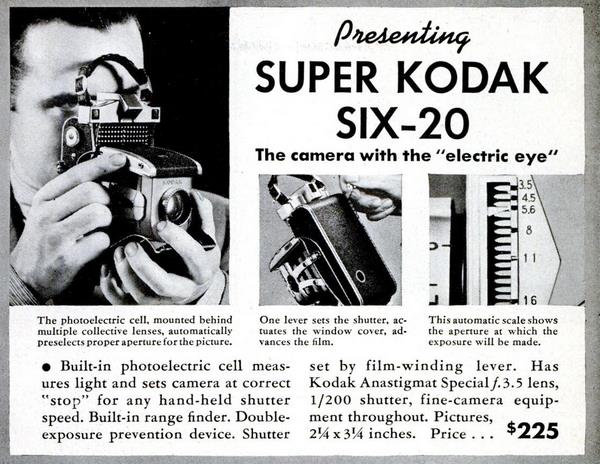

Cameras with built-in exposure metering have been around for a while.

On the left is an advertisement for a Kodak camera from 1938 that included a built-in exposure meter, and on the right is a picture of the first camera to include built-in exposure metering, the original Contaflex from 1935. (Later, the name would be applied to single-lens reflex cameras.) This particular camera was also unusual in being one of a very few twin-lens reflex cameras to feature interchangeable lenses.

Note that the Contaflex put the light-sensitive cell on the front of the hood shading the ground glass screen, thus avoiding having to increase the size of the front of the camera to make room for that cell.

Early cameras with this capability used selenium cells, as they produced electricity when hit by light, thus avoiding the need to add batteries to the camera. Cadmium sulfide (CdS) cells, on the other hand, did need to have batteries, as only their resistance changed on exposure to light, but they were more sensitive, and thus they were used on later cameras.

The first 35mm SLR with a built-in exposure meter was the Pentacon E (or Contax E); its light-sensitive cell was inside the pentaprism rater than being externally visible on the camera. This camera, from 1956, does not seem to have been credited as one with through-the-lens exposure metering despite that, however.

From 1963, the Yashica EE, shown at right, illustrates one common configuration of cameras with built in Selenium light sensors, found also in the Olympus Pen 55, for example, where the Selenium sensor is circular in shape and surrounds the lens.

Image by Danny H. from Pixabay |

A later example of how the 35mm SLR swept all before it is the camera shown at right from 1976. Yes, even the firm of Ernst Leitz Wetzlar, known for the storied Leica rangefinder camera, found the need to enter the SLR market.

The camera bodies were made in Portugal; note that the lens proudly proclaims that it is made in Canada!

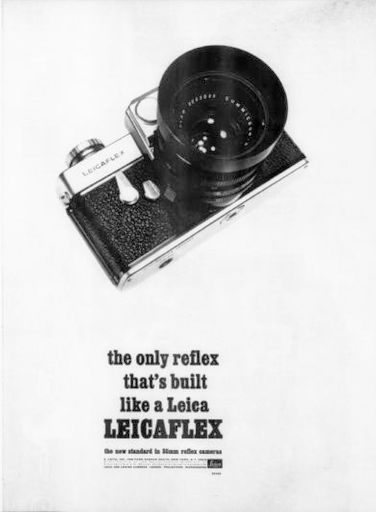

Actually, Leica was in the SLR business well before 1976; here is their Leicaflex SL from 1969. And, yes, there was an original Leicaflex, and that dated from 1964.

And here is how it was advertised, as you might well have expected.

The firm of E. Leitz Wetzlar, famous for the Leica rangefinder camera, was not the only company famed for making cameras of a different type that saw a need to join the 35mm SLR wave for fun and profit.

Thus, the German firm of Rollei, famous for their line of twin-lens reflex cameras, also started making 35mm SLR cameras, one example of which, the Rolleiflex SL35, is shown at left.

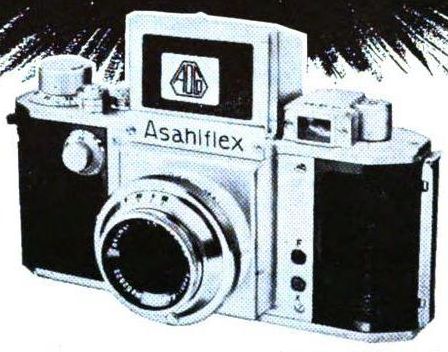

The first 35mm SLR produced by the Japanese firm of Asahi Optical, the Asahiflex, shown at right, did not have a pentaprism. But in a later model, they remedied that lack; that model was called the Pentax, and that was also what they eventually changed the name of their company to.

The Asahiflex was the first Japanese 35mm SLR, arriving in 1952. Although its lenses were attached to the camera by a screw mount, instead of the standard M42 screw mount with a 35mm opening, they used a screw mount giving a wider 37mm opening.

Before adopting the pentaprism, in the Asahiflex II, Asahi Optical brought an important innovation of its own to the 35mm SLR, the instant return mirror; before that, to make the mirror drop down, so one could again see what the camera was pointed at, one had to advance the film.

The image at right is from an advertisement which mentions the instant return mirror as one of the camera's features, so it is an Asahiflex II which is pictured there.