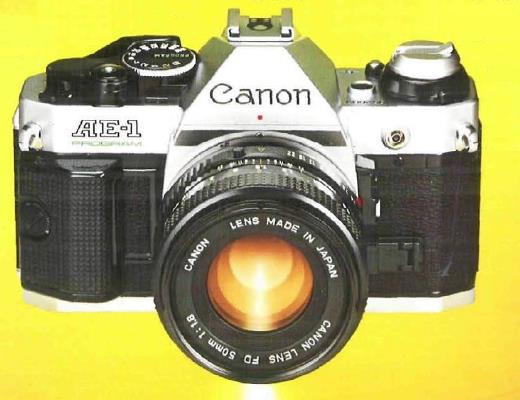

And the trend towards improved automation led to such cameras as the Canon AE-1 from 1976, pictured at left. It offered both aperture priority and shutter priority automatic exposure. And this was facilitated by its claim to a place in the record books... it was the first 35mm SLR to include a micdroprocessor within it. But, of course, it would be far from the last.

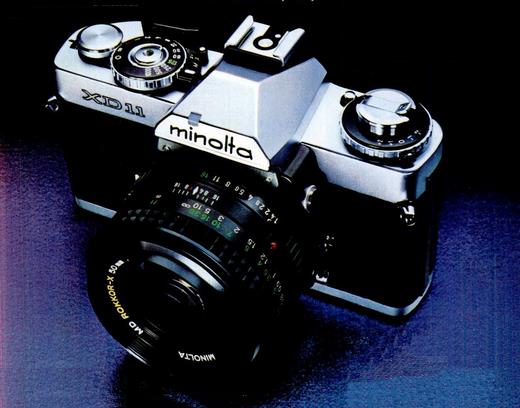

The year 1977 saw the introduction of the Minolta XD11, pictured at right, sold as the Minolta XD7 in Europe and simply as the Minolta XD in Japan. This camera also included advanced automation features, and was highly praised. It served as the basis for the design of some subsequent Leica reflex cameras, specifically the R4, R5, R6 and R7.

It was the first camera to offer the choice of all three of aperture priority automatic exposure, shutter priority automatic exposure, and manual exposure with metering information available.

It was the last camera from Minolta without autofocus to have a metal body instead of a plastic one. And the focusing screen on the camera was interchangeable.

Speaking of autofocus, in 1985 Minolta came out with the Minolta Maxxum 7000, the first camera in its Maxxum line. It was not the first camera made to include an autofocus capability, but it was the first that placed both the autofocus sensors and the motor used to adjust the focus of the lens within the camera body, so that the cost of lenses would not need to be significantly increased in order to provide autofocus.

This did require a new lens mount; the lens mount introduced with the Maxxum line of cameras continued to be used by SONY when it took over the consumer camera business from what was then Konica Minolta, and continued to be used in their Alpha line of digital SLRs.

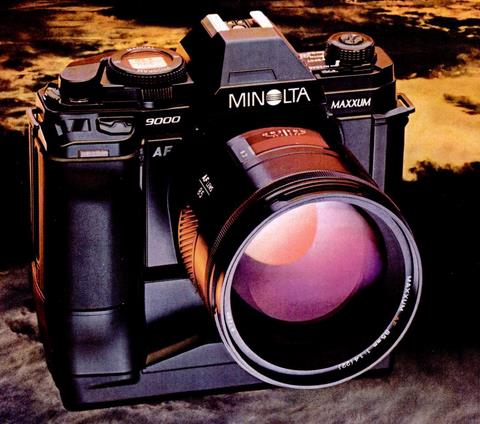

Later in 1985, Minolta went on to add the Minolta Maxxum 9000 to the line-up of Minolta Maxxum cameras with the new autofocus feature; this camera was aimed at professional photographers.

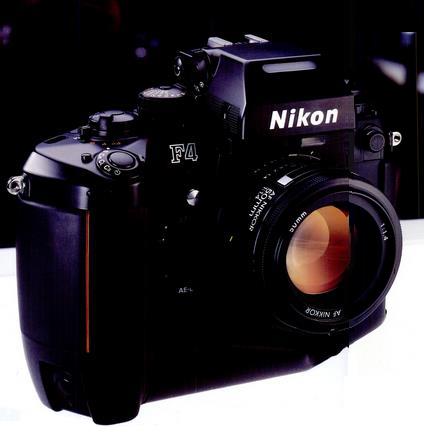

Not too long afterwards, in 1988, Nikon decided that its flagship professional cameras should include autofocus, and so they brought out the Nikon F4, with autofocus, to replace the Nikon F3.

However, back in April 1983, Nikon introduced the Nikon F3AF, so they had been one of the companies with autofocus cameras prior to the introduction of the Maxxum 7000. This camera is illustrated at right in a close-up from a recounting of Nikon's achievements in an advertisement for the later Nikon FG. The TC-16 teleconverter, available from Nikon, allowed several of their non-autofocus lenses to be focused automatically by the Nikon F3AF. So before the Minolta Maxxum 7000, Nikon had found a way to share one autofocusing motor between multiple lenses. A later version, the Nikon TC-16A, was made and it also had this capability.

The electronics for detecting focus was in a finder that could also be placed on existing Nikon F3 cameras to indicate when proper focus was reached to the photographer; the Nikon F3AF was modified by including electrical contacts on the camera body to allow operation of the focusing motor in Nikon AF lenses.

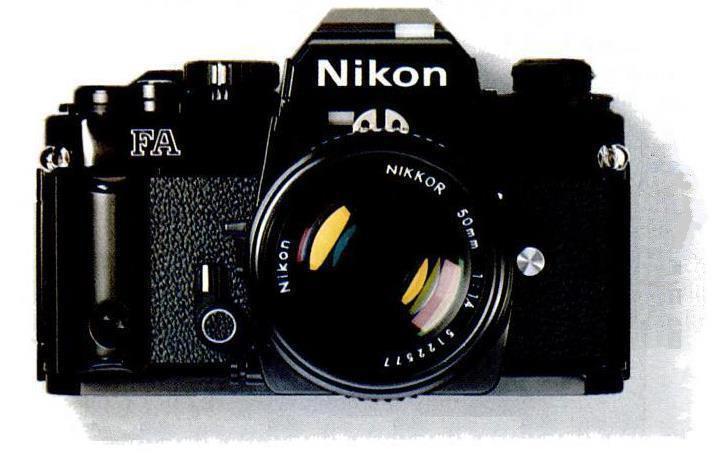

Another camera introduced in 1983 by Nikon was the first to offer matrix metering. That is, the brightness of the image was measured at a number of points in the image, and then the camera's electronics determined what was the likely type of image being photographed, and thus the appropriate weight to give the brightness readings at the different points in calculating the correct exposure.

This feature was termed Automatic Multi-Pattern metering at the time by Nikon.

A review of the camera I recently saw on YouTube claimed that it worked very well indeed.

Cameras can implement automatic exposure control in two basic ways; aperture priority, or shutter priority. If a camera doesn't have both, aperture priority is considered superior, because the f/stop setting of the lens affects depth of field and thus the appearance of the resulting photograph.

But having aperture priority automatic exposure means that the exposure circuitry needs to be able to control the shutter speed. That usually means the shutter needs to work electronically itself, which means that if the batteries run out, the camera can't take any pictures.

Many cameras addressed this issue by designing the shutter so that it could work manually at one shutter speed, such as 1/60 of a second or 1/125 of a second.

In 2001, Nikon came out with the FM3A, which was apparently the only film camera ever made that allowed one to toggle a switch which changed the shutter from electronic to mechanical operation, so that the camera could be used without batteries to take pictures at any of the shutter speeds shown on the shutter speed dial.

Despite being a film camera, this unique camera still sells for around $1,000 today (2025) on the used market.

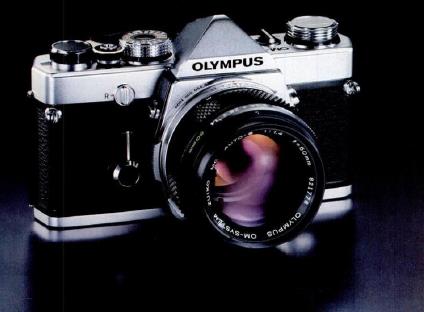

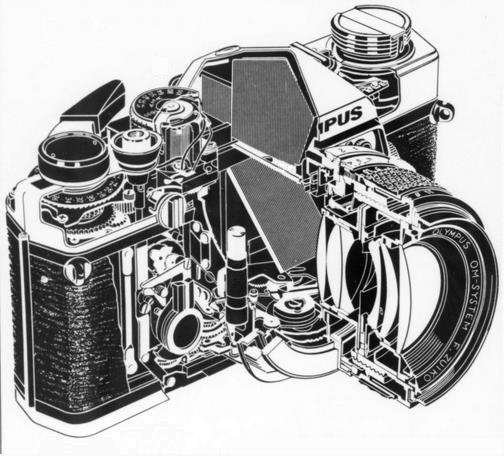

Of course, cameras competed in other attributes as well, besides autofocus and exposure automation. The Olympus OM-1 from 1972, pictured at right, was a plain manual camera, but its claim to fame was that it was the smallest and lightest 35mm SLR available.

It did offer other features as well. Some advertisements for it included this cutaway diagram, which illustrated that it had changeable viewfinder screens, and a damping mechanism to reduce noise and camera shake caused by the return of the reflex mirror in the camera.

As well, one of the lenses available for the camera had a unique feature.

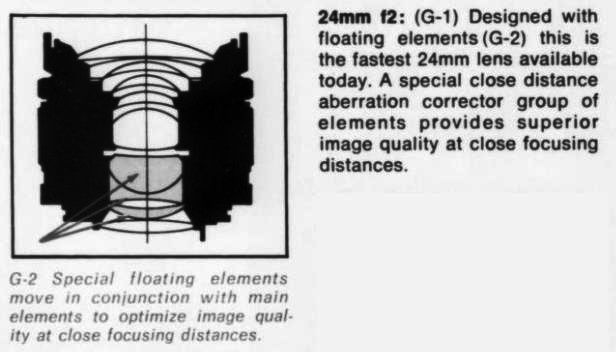

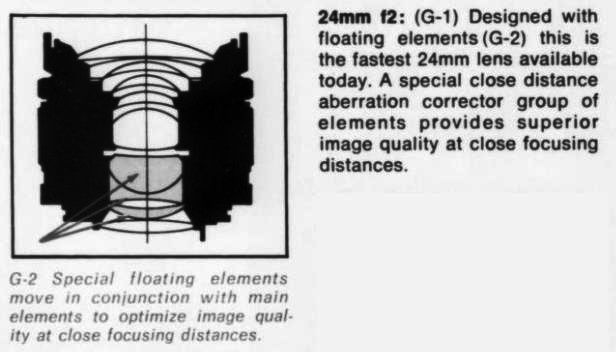

Zoom lenses work by having some of the elements within the lens move in order to change the focal length of the lens. Usually, ordinary lenses do not have any moving elements.

But when a lens is designed, it is usually corrected for one particular object distance and image distance. If a lens is corrected for use on objects at infinity, could it be that for close-up photographs, it could have problematic aberrations?

Apparently, this wasn't usually much of an issue. But for the Olympus OM-1, an extreme wide-angle lens with a 24mm focal length was designed with a group of elements that moved relative to the other elements when the lens was focused to address this concern, as pictured above.

A group of elements that moved when the focus of the lens changed was also used in Canon's f/1.0 lens for their SLR cameras that was introduced in 1989 along with the EOS-1.

A significant 1988 introduction was that of the Olympus Infinity SuperZoom 300. Sold as the AZ-300 in other markets, this camera attempted to bridge the gap between simple point and shoot cameras and SLRs by offering a built-in zoom lens, and a viewfinder with automatic parallax correction. And indeed, cameras like this are now termed "bridge cameras".

This camera won the European Camera of the Year award.

This film camera was the forerunner of what is now a major genre of digital cameras from many manufacurers.

|

The image above is from the Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is Runner1616. |

However, this was not the first film camera to come with a zoom lens built-in as a fixed, non-interchangeable, lens. In 1963, Nikon offered the Nikkorex 35 Zoom, pictured at right.

And it's an SLR, which, of course, provides the simplest and most direct method of allowing the consequences of the setting of the zoom lens to be visible in the viewfinder, whereas the later Olympus camera required extra complexity in the viewfinder to achieve this.

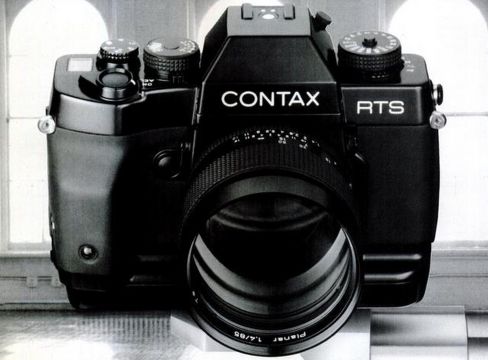

An interesting film camera from 1990 is the Contax RTS III. This camera did not include an autofocus feature, which was somewhat unusual for new cameras at that date. But it did include a unique premium feature. Behind that part of the film which was behind the focal-plane shutter... was a flat ceramic plate... with tiny holes in it, out of which air was pumped.

It had a vacuum system so that the film would be held flat during picture-taking to improve the quality of images.

This camera was billed as "The first camera for perfectionists".

This was not necessarily a bad idea, although if no other camera maker considered it worth the trouble, one might be suspicious. In any case, with digital cameras, the sensor must be perfectly flat, and so the issue has been addressed without any direct effort towards doing so.

The technique of using a vacuum plate to flatten film has been used elsewhere. It is used in IMAX cameras. A vacuum back was available as a third-party product for Hasselblad cameras, and vacuum backs have also been offered for use in astrophotography.

The specialized cameras used for aerial photography also had vacuum backs in many cases. So, rather than being unprecedented, this was a standard technique where film, instead of glass plates, was used for photographic applications requiring the highest precision.

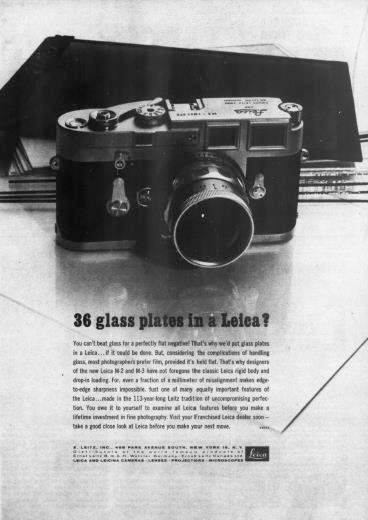

Indeed, one could even say that the Contax RTS was a dream come true. In 1962, Leica ran the advertisement shown at left in which it notes that it took care to ensure the bodies of their cameras were rigid, and the film path was designed with care and precision to ensure the film was held flat to be exposed. While they couldn't go further, as the advertisement said, by having one put 36 glass plates in the camera instead of a 36-exposure roll of film, the Contax RTS, with its vacuum back, finally came as close to that dream as possible.