The minor imperfection of a mirror-reflected image, of course, can be corrected by going to the famous Single-Lens Reflex type of camera.

Such cameras have been around for a long time; Wikipedia notes that the principle was patented in 1861, and by 1885 the Monocular Duplex was being sold commercially.

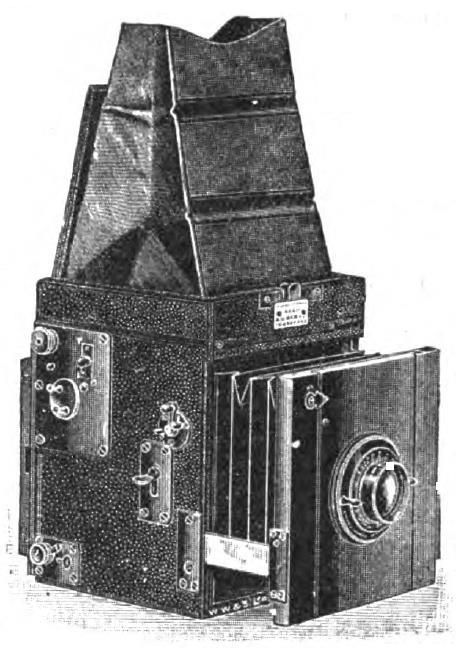

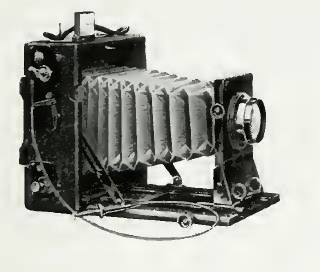

Pictured at left is a single-lens reflex camera from 1910, Watson's "Argus" Reflex. It even has a focal-plane shutter.

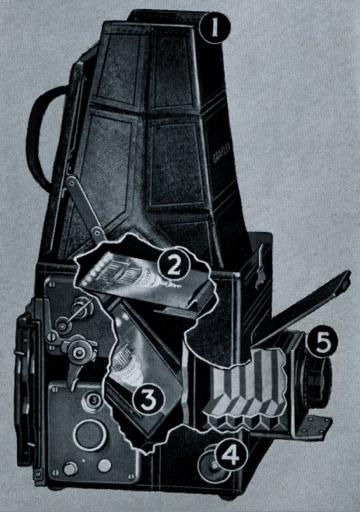

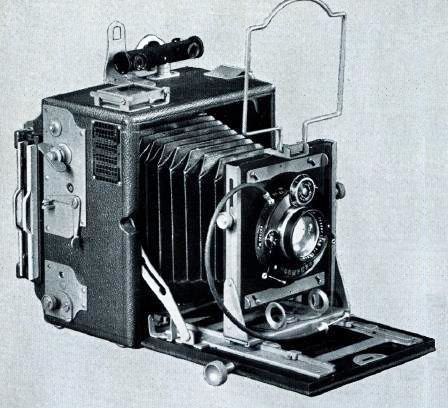

And pictured at right is a single-lens reflex camera from 1936 by Graflex, the National Graflex Series II.

The diagram shows how it works; the lens (5) is a relatively simple one, and so it has no back focus issues, and there's even a bellows (4) to extend it out.

A mirror at a 45-degree angle (3) reflects the light to the ground-glass plate (2) on which the image is viewed; it flips up out of the way when a photograph is actually being taken in order to let the light reach the film behind it.

And there is a shade (1) around the ground glass to allow the photographer to see the image when looking down at the camera.

This camera used standard 120 roll film, and was reasonably compact and easy to carry. Note, however, that because it doesn't have a pentaprism, it still does have a viewfinder image that is mirror-reflected.

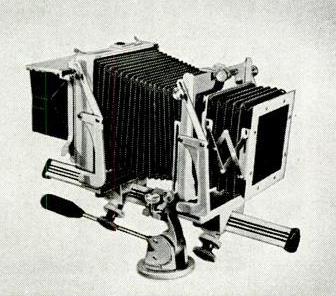

A larger SLR from Graflex, the Home Portrait Graflex, required a 5 inch by 7 inch plate or film area; it offered tilt and rotate movements with its bellows for control of perspective.

Watson's "Argus" Reflex was a British camera; 1936 happened to be the year where a camera company was founded in the United States that took the name Argus. The reason this is a good name for cameras is that Argus was a giant in Greek mythology who had many eyes, and thus could see in all directions. Initially, he just needed four eyes for that, but later on they settled on a hundred eyes.

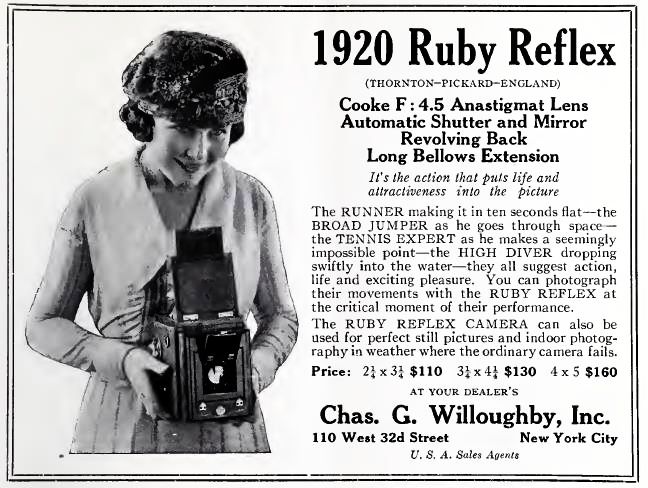

And at right, I show a 1920 advertisement for a single lens reflex camera, to give additional evidence that such cameras really existed back in those long-ago days. However, with the prices starting at $110 in 1920 dollars, and with the camera using plates, rather than roll film - which, of course, was already available back in 1920 - while such cameras may have existed, I cannot claim that this advertisement is evidence that they were particularly common. But presumably somebody was buying and using them.

Graflex is also the company that made the Speed Graphic camera, pictured at right, which was widely used by newspaper reporters at one time, perhaps from the 1930s to the 1950s or so.

The Speed Graphic included some limited capability of adjusting the position of the front plate of the camera with the lens, so as to allow certain perspective effects to be created with the camera. Graflex also made view cameras, such as the Graflex View II shown at left, which allowed more flexibility in this area.

Assuming a lens which can cover a larger area than that of the film, if one moves the front of the camera vertically upwards, then the image on the film will be, essentially, a different portion of a wide-angle photograph. The most common and obvious use of this is for photographing a tall building; if one does this, instead of tilting the whole camera to point it upwards, one can get a photograph of the building in which its sides are parallel instead of converging due to perspective.

Tilting the front of the camera from side to side can let one make use of the "Scheimpflug rule", so that even with a limited depth of field, one can have distant objects in focus on one side of a picture, and close objects in focus on the other side.

And while I thought that such matters as the Scheimpflug rule were far beyond the scope of these pages, since I can hardly mention view cameras without saying what they're good for, the diagram at right shows that, when the front of a camera is tilted, the line where the film plane and the lens plane intersect... is also the line that is intersected by the various planes of objects that can be brought into focus at the same time.

Of course, the "lens plane" would actually be two planes, one for each of the principal planes of the lens of the camera, but those who know enough optics to understand such things can work it out for themselves.

The history of Graflex, I have recently learned, was more interesting than I might have expected. Graflex was founded in 1887, and was originally called the Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company. The interesting bit is that it was acquired by one George Eastman in 1909. Later, however, Kodak was compelled to divest itself of Graflex, presumably for antitrust reasons.

Pictured at left is an early Speed Graphic, made while Graflex was a division of Kodak.

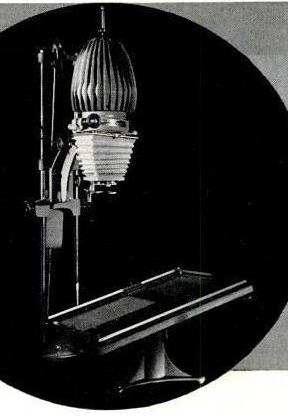

Graflex branched out of its niche of making reflex cameras, press cameras, and view cameras to enter the general camera market. Thus, it came out with the Graphic 35, a rangefinder 35mm camera, as shown as left, during the 1950s. Also, it even made enlargers, such as the Graflex Anniversary Enlarger, shown at right.

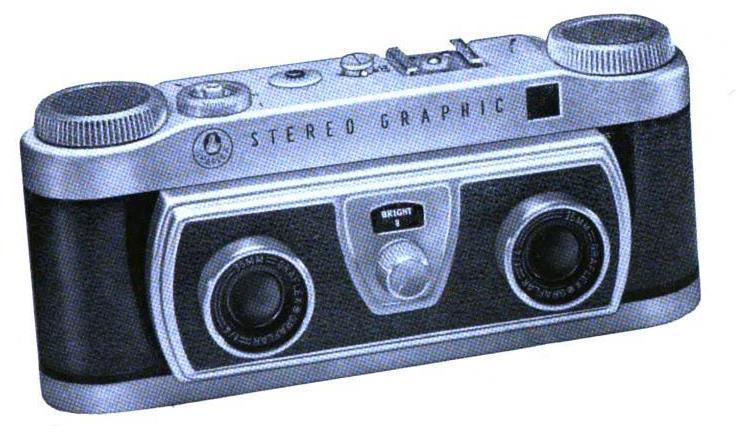

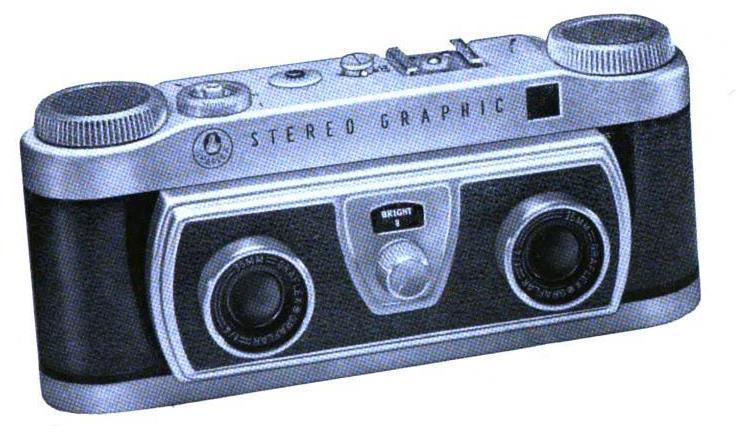

They even made a stereo camera, the Stereo Graphic, shown below.

The view camera embodies an alternative to the single-lens reflex for previewing the exact image to be photographed. Generally speaking, though, the design is only applicable to glass plates: first, focus the image on the ground glass plate, and then replace it with the holder containing the glass photographic plate to be exposed.

We have already seen the Primarette, a twin-lens camera where the upper chamber simply had a ground-glass plate on the back, with no reflex mirror, so that the camera could be folded up flat when not in use.

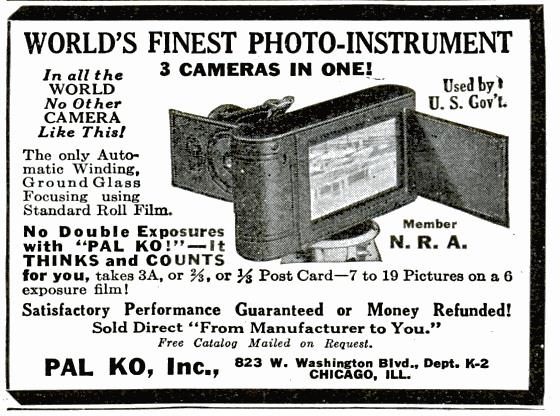

Another way in which the view camera principle could be applied to roll film was demonstrated by the now little-known Pal Ko camera, an advertisement for which is shown at right. This camera got the film out of the way of the ground glass plate on the back by winding it back on to the supply spool as that spool was moved across the exposure area on rails.

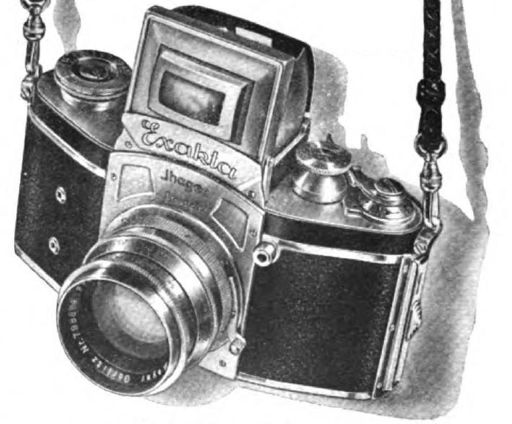

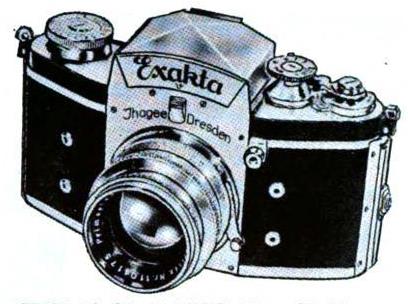

In 1933, the German firm of Ihagee started making and selling a single-lens reflex camera that used 127 film. The illustration at left shows their Model B Exakta, with the additional interchangeable lenses available for it, as the caption in the image notes.

This camera's design formed the basis of the design for their following product, which made history, although that may not have been obvious at the time.

The Kine Exacta, originally sold in 1935, and which continued to be made in East Germany after the war, is generally considered to be the very first single-lens reflex camera which used 35mm film. It used the same 36mm by 24mm image format as established for still photography by the Leica. To take a picture, one looked down at the ground glass plate, which was surrounded by a shader, as with the Graflex above.

In the Soviet Union, at least, someone was quick to recognize the significance of the Kine Exacta, as it was in 1936, the very next year, that the first version of the Sport 35mm SLR, shown at left, began being produced there.

In 1949, the East German portion of Zeiss, Carl Zeiss Jena, offered the Contax S camera to the world.

This was not the first 35mm SLR to feature a pentaprism, the Rectaflex, shown at left, from Italy having preceded it by a year. But the Rectaflex was not nearly as successful.

The Contax S also introduced the M42 screw mount, which became the standard mount for 35mm SLRs until more elaborate arrangements for connecting the lens to the camera were required for such features as automatic exposure with shutter priority, in which the camera needs to have control over the f-stop setting in the lens, and, much later, autofocus as well.

Another very early 35mm SLR with a pentaprism was the Alpa Prisma-Reflex from Switzerland, shown at left.

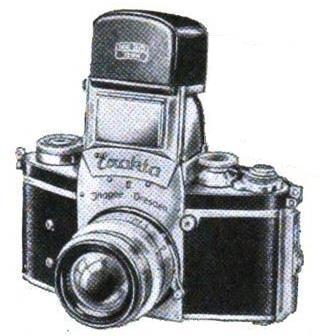

The Exakta Varex, sold as the Exakta V in the United States, shown at left, was another very early camera to offer a pentaprism. In this camera, the pentaprism could be removed, both to allow the focusing screen to be changed and to allow switching to waist-level viewing.

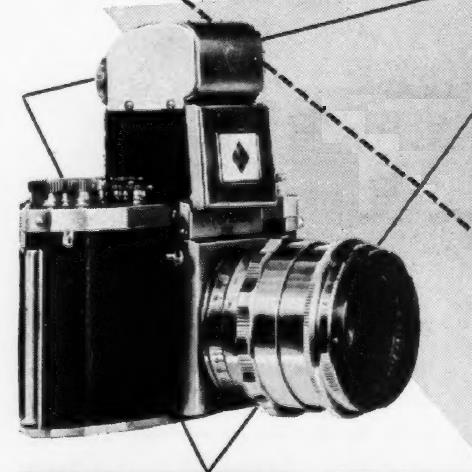

Before the later models of the Exakta mentioned above were introduced, a pentaprism attachment that sat on top of the shader hood for an older Exakta was offered for sale, as pictured at right. This is also how a pentaprism option was provided for the original Praktica fx camera, as shown in the slightly retouched detail from an advertisement shown at left. A pentaprism in the normal position, of course, was available for the later Praktica fx2.

Incidentally, on the previous page I noted that it was possible to turn any rangefinder camera into a twin-lens reflex by clipping the top half of a twin-lens reflex camera to it.

A more common accessory, called a reflex housing, existed to turn rangefinder cameras into single-lens reflex cameras, called a reflex housing. The Delta Scope, an example of this from 1948, is shown at left.

This has the obvious issue, though, that it requires lenses which not only must have a larger back focus than those available for the original rangefinder, but because of the thickness of the rangefinder body, also need lenses with a larger back focus than typical for an SLR.

Rather than providing specialized lenses for these attachments, they were generally sold as specialized devices for close-up macrophotography only.

However, it turns out that there was at least one exception to this generalizaton.

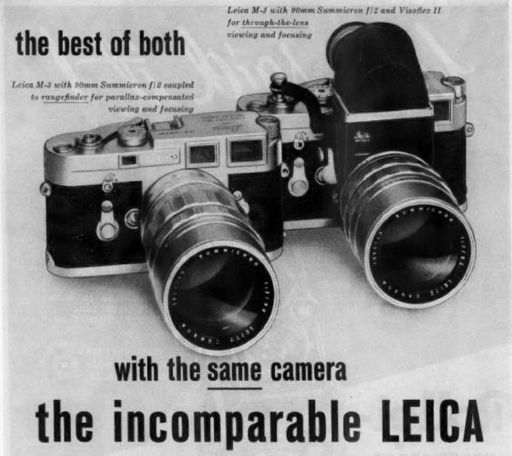

At one point, Leica offered the Visoflex II, an accessory for their rangefinder cameras, which was intended to allow them to be used as single-lens reflex cameras with general application. A section for an advertisement for this accessory is shown at right.

While this may be considered a peculiar camera accessory, and a bad idea - and Leica did eventually get around to manufacturing and selling conventional single-lens-reflex cameras in time - I can think of a use for such a device in a different context at the present time.

As I note on a later page, the Pentax K-1 digital camera, a full-frame DSLR, came out later than full-frame DSLRs from other makers, and so it is still somewhat expensive on the used market. While the Canon 5D, a now inexpensive full-frame DSLR, has a shorter flange-to-film distance, and a wider lens opening on the camera body, than a camera using M42 screw-mount lenses, it still can't use M42 screw-mount lenses with an adapter without problems - although this has been achieved by the expedient of trimming away a small bit of the reflex mirror.

Obviously, though, there would be no difficulties of this kind if an adapter were used to couple an M42 screw-mount lens to a mirrorless digital camera. But a problem of another kind appears; while the LCD display on the back of a digital camera is fine for composing a photograph, it isn't really adequate for the purpose of manual focusing.

An M42 adapter which included a small reflex mirror along with a viewfinder, similar to the Leica accessory shown here, would solve that issue nicely, enabling a large selection of classic lenses to be easily put to use.