The image above is from Flickr, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms.

Its author is s58y.

At left is an image of a Beseler Topcon Super D camera. This camera, sold in Japan as the Topcon RE Super, was the first 35mm SLR to offer through-the-lens metering in 1963. Topcon cameras, made in Japan, were sold at premium prices. For this reason, it did not make a big splash on the market. It used a Cadmium Sulfide cell to measure the light, which meant it needed to have batteries to use it, in order to have greater sensitivity to light. This was necessary to make through-the-lens metering possible.

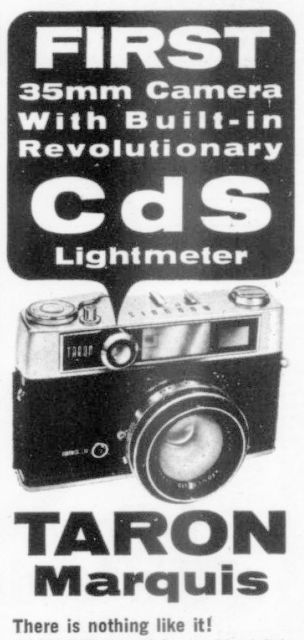

The first camera to use a Cadmium Sulfide cell came out in 1962. This camera only used it for ordinary light metering in the same way Selenium cells were used. It was a rangefinder camera, and it did not even have interchangeable lenses. But the built-in lens was a 45mm f/1.8, so at least it was reasonably fast.

The camera was the Taron Marquis, and because it was a rangefinder without interchangeable lenses, it is largely forgotten today. Part of an advertisement for it is shown at right.

|

The image above is from Flickr, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is s58y. |

The ALPA-Reflex 9D, also introduced in 1963 with through-the-lens metering as well, did not make a big splash in the market either; it was made in Switzerland, after all. In fact, only a small number of those cameras were ever made.

I have now seen accounts stating that it came out slightly before the RE Super from Besseler Topcon, making it the first camera with through-the-lens metering.

Note from the image at left that ALPA was still using the old style of automatic lens at this late date!

However, when 1964 came along, Pentax brought out their Spotmatic camera, which offered through-the-lens metering at an affordable price, and it very shortly became the biggest selling camera in the U.S., and it remained so for several years. (It required batteries, and also used Cadmium Sulfide cells.)

Initially, the camera was designed to use spot metering, but this was changed to center-weighted metering during the design process, as it was felt spot metering would end up causing some photographers to make mistakes in exposure; but it was too late to change the camera's name when that was done!

Of course, other camera makers noticed the success of the Pentax Spotmatic, and made an effort to compete.

As just one example, in 1966, Minolta came out with the SR T 101 camera, pictured at right, which offered through-the-lens spot metering.

The Canon Pellix, introduced in 1965, which we examined earlier when reviewing the basic components of the SLR camera, had its special feature of a pellicule instead of a normal mirror specifically in order to improve its own through-the-lens metering feature, so it, too, was part of the response to the Pentax Spotmatic.

And, as we've seen, Nikon entered the fray in 1965 as well, with the Photomic T version of the Nikon F pentaprism.

Later, in 1968, the Mamiya/Sekor 500 DTL and 1000 DTL aimed to offer a major improvement by providing both spot metering and average metering, which the photographer could choose between with a switch on the front of the camera.

All the cameras surveyed above from the Pentax Spotmatic to the Mamiya/Sekor 500 DTL and 1000 DTL still required the photographer to manually set the lens aperture and the exposure time; the light meter built into the camera simply was intended to give more accurate information with which to do this.

Later on, cameras gained the ability to automatically set the exposure time and then even the lens aperture - which required a change to the lens mount.

The Konica Autoreflex T from 1968 was the first 35mm single-lens reflex to adjust itself to the correct exposure in response to the information from its light meter, rather than simply assisting the photographer in making the adjustment; its metering was neither averaged nor spot metering, but center-weighted. This camera was an early and successful product for its maker, establishing Konica as a serious competitor in the SLR marketplace.

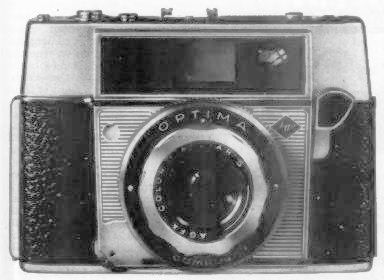

However, as far back as 1959, the Agfa Optima was offering to automatically set both the aperture and the exposure time in response to the exposure conditions. Of course, as this was neither aperture priority nor shutter priority, and it was also based on the signal from a selenium cell rather than from a through-the-lens exposure system, it was not ideal, but it was an automatic exposure system that did precede the Konica Autoreflex T.