As we saw on the previous page, 1959 was the year when Nikon brought out the Nikon F, which was destined to become the top choice of photojournalists for over a decade.

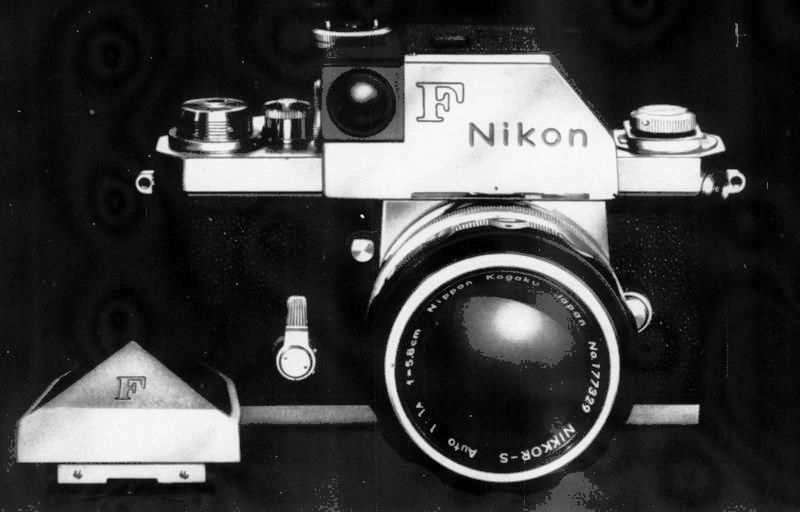

And, in 1962, they introduced a pentaprism finder with a light meter built in, making the camera what was called the "Nikon F Photomic":

As it happens, Exakta was there first; they offered a pentaprism finder with a built in meter for the Exakta VX IIa back in 1958.

Like the Nikon F Photomic, their light meter took its reading through a window in the front of the pentaprism enclosure, not from the light going through the pentaprism, so it did not offer through the lens metering.

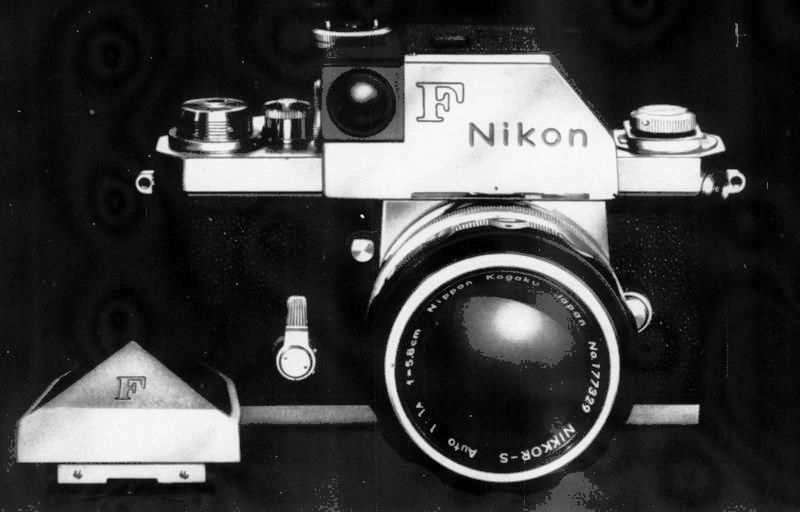

Eventually, Exakta would make good that lack, with the Examat, but that would only arrive in 1969, whereas it was in 1965 that Nikon switched to through-the-lens metering with the Nikon F Photomic T, an advertisement for which is shown at left.

|

The image above is from Flickr, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is s58y. |

Incidentally, the original Photomic pentaprism finder was not the first built-in metering option for the Nikon F. At the introduction of the camera, one accessory offered was an exposure meter attachment using a selenium cell. This accessory went through three different versions before the Photomic finder was introduced.

An image of the Nikon F with a meter in the third of those versions is shown at right.

While the pentaprism is not part of this meter attachment, note how it couples both to the exposure time selection knob, and the aperture linkage of the lens, just as the Photomic pentaprism did.

The first and second versions of this meter attachment were similar in configuration to the third version shown, but differed in appearance in one respect: the selenium solar cell used for sensing the light was larger, extending across nearly the full width of the meter.

On the first page of this site, I note that had Leica elected to advance the film by seven perforations instead of eight after each exposure, they could have kept the 4:3 aspect ratio of motion picture film for still picture film, and this might have been a superior format, as well as saving film.

Nikon's first rangefinder camera, the Nikon I, actually did attempt to use this format. Their original intention was to make their rangefinder camera exclusively for export, because it was felt the Japanese economy was such that a camera of that high quality would not sell well enough in Japan. But this collided with the fact that at least in any country outside Japan, if not also in Japan too as well, processing laboratories would assume 35mm had one picture for every eight sprocket holes in the film, and so films shot on that camera could not be processed properly.

So it could not be exported; the design of the camera was modified so that it did advance the film by eight sprocket holes after every picture, but the size of the picture couldn't be widened immediately, because to do so would require time-consuming and expensive changes to dies used to mold components of the camera.

Therefore, Nikon's next camera was the Nikon M, which put 24mm by 34mm photos on a 35mm film at every eighth sprocket hole, even though that wasted film; at least, even without redesigning the body, they were able to widen the frame somewhat from the original 4:3 aspect ratio 24mm by 32mm size, thus making the shortcoming less noticeable. Existing stocks of the Nikon I were converted to be Nikon M cameras to make them saleable. Given the... inefficiency... of the Nikon M, I would have thought that even it could only be sold at fire-sale prices; who would want what is obviously a defective camera? (And, in fact, the Nikon M wasn't sold at fire-sale prices, it was a rather expensive camera.) Of course, I suppose that would have solved the problem of being able to sell it in the economy of war-ravaged postwar Japan; I wondered how Nikon managed to survive this setback, until I remembered that they didn't only sell cameras: they sold lenses, and their lenses were popular because of their high quality, and they were available for cameras other than Nikon cameras, including the Leica. So there was cash flow.

I have, though, learned additional information: Nikon did not have a choice about exporting the Nikon I. According to one source, its export was prohibited by American occupation authorities; according to another, it was the U.S. importer that refused to accept a camera with a non-standard image format, with the role of the U.S. government being limited to refusing to allow the camera to be sold in military canteen stores. Also, its seven-perf format was a Japanese standard at the time, having already been put into practice by Minolta, in their Minolta 35 camera. This suggests that the Nikon I would have been saleable in Japan, and the Nikon M was able to be exported... and somehow found a market.

Also, while they couldn't modify the camera enough to let it take pictures on a full 24mm by 36mm frame, as noted above they were still able to increase the size of the frame from 24mm by 32mm to 24mm by 34mm, making the limitation less noticeable. And that must have worked, since the Nikon S, which definitely was a success in the American market, still didn't have a fully-redesigned body capable of handling the standard frame; its difference from the Nikon M merely consisted in the addition of flash synchronization contacts.

Thus, an idea that seemed good, but conflicted with practical real-world considerations, nearly killed the company in its infancy. And yet they managed to survive and eventually make a properly modified rangefinder camera, the Nikon S2, which now took standard 3:2 pictures on those eight perforations, which ended up being a huge success due to its superior quality.

It is a great pity there wasn't some way to make it possible for film processing laboratories to become more flexible; but Nikon wasn't Kodak, and so it didn't have the power to set the standards for film formats.

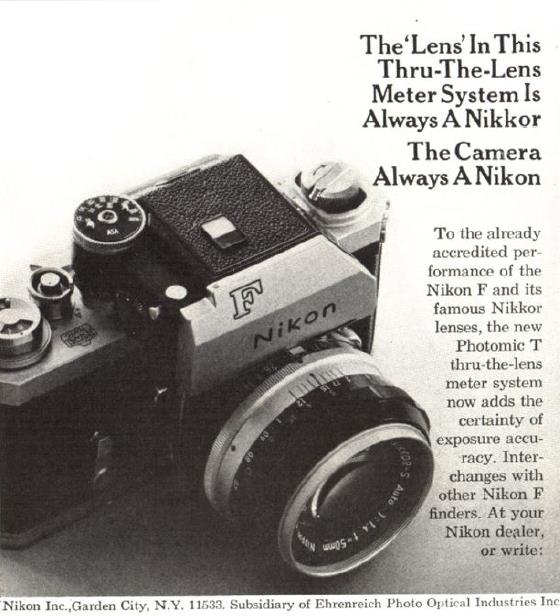

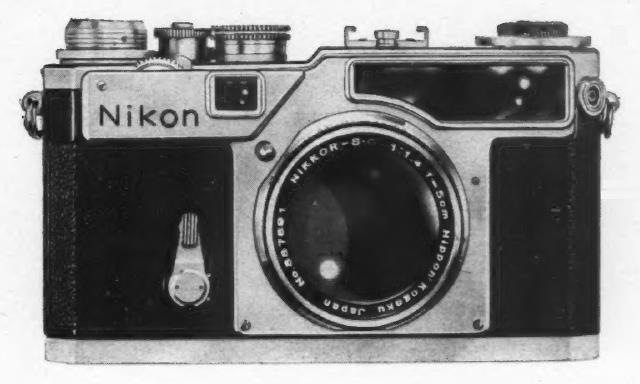

Pictured at left is a Nikon S-2 rangefinder camera. This camera preceded the Nikon F, and it was advertised as "the Fastest Handling '35' in the field", certainly an attribute of value to news photographers. Its predecessor, the earlier Nikon S, was widely used by news photographers covering the Korean War, and their familiarity with this Nikon product is likely to have contributed to the merits of the Nikon F camera being quickly recognized.

A renowned American combat photographer, David Douglas Duncan, who was instrumental in introducing Nikon to the American public, however, never used a Nikon rangefinder camera. Instead, his camera was a Leica - but while on a visit to Japan, in June of 1950 he met Jun Miki, a Japanese photographer who, like him, worked for LIFE magazine, who introduced him to Nikkor lenses - and he bought a set of the full assortment available and used them on his Leica from then on. Later on, he did end up using a Nikon F camera when that came out, though. As he worked at LIFE magazine, word spread to his colleagues, and one of them, Hank Walker, got a Nikon S camera in addition to Nikkor lenses, and in extreme cold conditions (about -30°C or -22°F) in Korea, his Nikon S functioned without issues while the other photographers were struggling. A New York Times article of December 10, 1950 discussed the popularity of Nikon among professional photojournalists, and, of course, this meant that Nikon gained a great deal of recognition at that point. The article discussed the superiority of Nikkor lenses, and mentioned that the camera was also of superior quality, but it did not say anything about its cold-weather performance, which is what seemed to me to be the most dramatic difference from the competition, so I can only guess that the word about that spread through other means.

Oh, and I finally located an image of the actual Nikon S, which is shown at right; the advertisement in which I saw it simply referred to it as "The Nikon camera", as it was the first and, at the time, the only, model of camera from Nikon that was available in the United States.

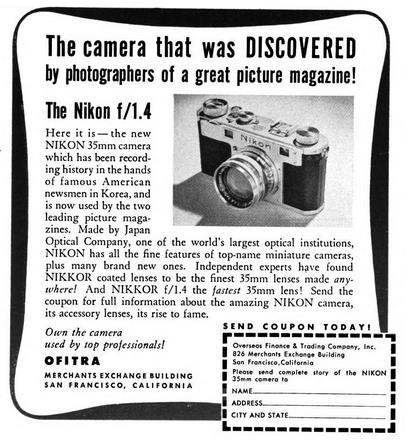

In fact, this advertisement for the Nikon S by an importer, from the April and May, 1951 issues of Popular Photography even refers to this bit of history - how the Nikon S was used for photojournalism in Korea, and then became popular with photographers for a major pictorial news magazine. It was the first Nikon advertisement to appear in that magazine; in February 1951, an article noted that Nikon was hoping to manufacture enough of their cameras to begin exporting them to the United States later that year.

Although they couldn't mention its name in the advertisement, for legal reasons involving trademarks and implied endorsement, it is well known that the Nikon F was used by many photographers for America's most prominent pictorial news magazine - LIFE magazine. And the two leading picture news magazines would have been LIFE and LOOK at the time. (As well, the New York Times article mentioned above did refer to those two magazines by name.)

Also of interest is that a few months later, in the August, 1951 issue, an advertisement in the same format as this one was placed by the Nikon Camera Company, "an affiliate of Overseas Finance & Trading Company, Inc.". So they were taking being the importer of Nikon cameras very seriously, and things were moving fast.

In 1954, however, just a few years later, Ehrenreich Photo-Optical became the sole importer of Nikon products to the U.S. instead, under the name of Nikon Incorporated. In 1981, Nikon acquired Ehrenreich Photo-Optical.

In 1958, just before coming out with the legendary Nikon F, Nikon brought out a new model for its line of rangefinder cameras. An advertisement for this camera stated "It is, in fact, the first rangefinder-coupled 35 to fully realize the benefits of lens interchangeability". What this was referring to was the fact that this camera had two viewfinders; the main viewfinder had rectangles showing the size of the image frame for 50mm, 85mm, 105mm and 135mm lenses; the second viewfinder showed the frame for 28mm lenses with a rectangle showing the frame for 35mm lenses.

Not only did the Nikon SP continue to be sold after the introduction of the Nikon F, but there were also a Nikon S3 and a Nikon S4. However, the Nikon S4 is rare, having been available only briefly, and it was never sold in the United States. The Nikon S3 and S4 also date from 1958; while the S, S2, and SP were successors, the S3 and S4 were additional models offering less expensive rangefinder cameras with fewer features as an option.

According to one web page I've seen, the Nikon F wasn't designed completely from scratch, but instead incorporated much from the Nikon SP. If so, this could account for the fact that the Nikon F and Nikon SP were initially sold for the same price, $329.50, as one contemporary advertisement noted.

The street price for a Kodak Retina Reflex S, at the time, was $136.95, and I believe that was considered to be an expensive high-quality camera; and for an Argus C-3, the street price was $39.95... so the appeal of Nikon F did tend to be limited to serious professionals.

An early advertisement for the Nikon SP, at its introduction in 1957, referred to it as "a camera destined to play an important role in aiding those who draw upon its qualities to achieve new heights of creativity, and leadership in their work". Given how the Nikon SP was so overshadowed by its successor, the Nikon F, and, for that matter, by the success of the SLR in general, this of course seems overblown, but if the Nikon SP lived on in the Nikon F, then in a way it still fulfilled that destiny.

Earlier, I noted that the Nikon S was popular with photojournalists covering the Korean War, and this could have explained why people in that field were willing to give the Nikon F a try, allowing its merits to be observed quickly.

It is often noted, also, that Nikon cameras and lenses are of high quality.

While these two are important factors, I don't think they're enough to explain the great success of the Nikon F. After all, there are other 35mm SLR cameras that not only were advertised as being of high quality, but were generally acknowledged to be such... the Beseler Topcon, the ALPA, even the Leicaflex, for example.

The Nikon F offered quality and reliability; but it also offered fitness for purpose to photojournalists; it was designed to be responsive, and the layout of its controls was well-thought-out, so that it was a very good camera for taking pictures when you were in a hurry. And that was exactly what photojournalists needed the most. And, of course, being usable at -22° temperatures was also highly relevant to photojournalists, who are often called upon to work in adverse weather conditions, and, as noted above, Nikon cameras shone in this area as well, even in comparison to rivals otherwise famed for their high quality.

This has carried on to the present; in comparisons between the Nikon D700 and the Canon 5D as choices for someone looking for an older inexpensive full-frame DSLR, it was noted that the colors of photos taken by the Canon 5D looked better, but the Nikon D700 was easier to use, with many functions having buttons on the camera to control them that required diving into the menus of the Canon 5D.

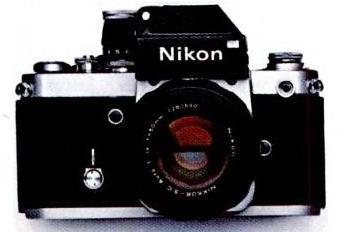

Shown at right is the Nikon F2, which came out in 1971 as the successor to the Nikon F. This camera used the same focusing screens as the F, but not the same viewfinders. As with the Nikon F, exposure metering was performed in the pentaprism module, but in the F2, the battery that would power the exposure meter was placed in the camera body.

Announced with this camera, but not immediately available, was the EE Aperture Control System, later sold as the DS-1 EE Aperture Control Attachment. This provided automatic exposure control to the camera. There were several models of the Aperture Control Attachment, each one matched to a particular model of the pentaprism finder with metering: the DS-1 for the DP-2 finder from the F2S camera, the DS-2 for the DP-3 finder from the F2SB camera, the DS-11 for the DP-11 finder from the F2A camera, and the DS-12 for the DP-12 finder from the F2AS camera. Note that the finders are sometimes referred to by the name of their associated camera version.

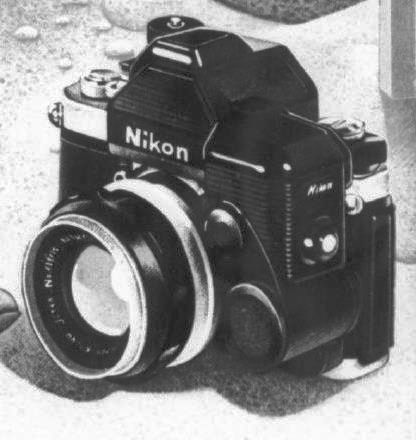

An image of a Nikon F2 fitted with this type of attachment is shown at left. The attachment includes a ring that goes around a ring situated behind the flange on the Nikon F2 body; that ring, on the camera, connects to the part of the lens that allows the aperture to be set automatically. Originally, I thought the ring went around part of the lens, but when I saw a picture of the attachment on a camera body without the lens present, in which the ring seemed to be missing, I searched further to find out what was going on.

This attachment required the use of the newer AI lenses for the Nikon, which continue to be required with modern Nikon DSLR cameras to avoid damage to them, although they usually require lenses with additional new features to make use of all the capabilities of the camera, such as auto-focusing. The Nikon F2 itself, without this attachment, was compatible with all previous Nikon lenses, so it is the Aperture Control Attachment that is associated with the origin of the AI lens.

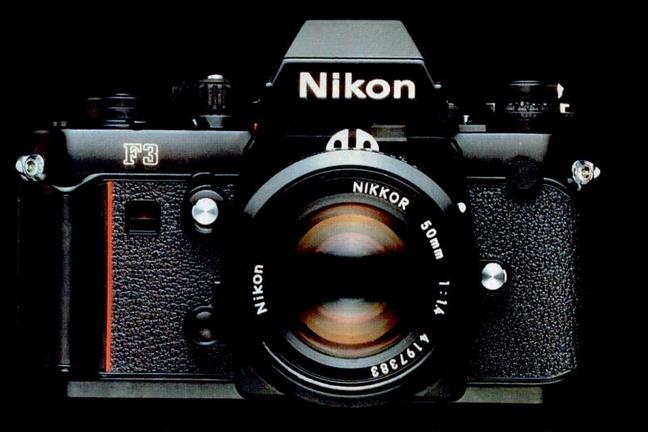

And shown at left is the Nikon F3, the successor to the Nikon F2. This camera came out in 1980. The Nikon F, the Nikon F2, and the Nikon F3 all have removable viewfinders. This allowed Nikon F and Nikon F2 cameras to be upgraded to include automatic exposure control, and it also allowed the ground glass screen to be exchanged for ones having different designs in which the features for assisting in focusing the camera were different.

One major difference between the F3 and its two predecessors was that the exposure meter was now a standard feature, and built into the camera body. Although it used AI lenses (and could also use non-AI lenses with limitations), a type of lens introduced, as we saw, to work with an automatic exposure attachment that worked by setting the aperture of the lens to correspond to the light, and it did have automatic exposure, not just metering, it didn't attempt to change the aperture setting of the lens; instead, as it had an electronic shutter, it went with aperture-priority automatic exposure, changing the time of the exposure to match the lighting conditions.

Another Nikon F3 first is that the Italian designer Giorgetto Giugiaro (primarily famed as an automotive designer) was commissioned to design the styling of its body.

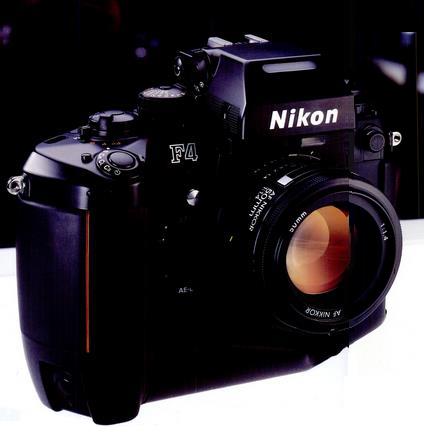

The Nikon F4 (1988), shown at right, also had interchangeable pentaprism finders,

and so did the Nikon F5 (1996), shown at left.

The Nikon F6, from 2004, the final film camera in this line, did not have a removable pentaprism, but the focusing screens were still interchangeable. In the January 2005 issues of photography magazines, Nikon was already advertising their D2X digital SLR instead of this camera, their top-of-the-line film SLR.

From a review of the Nikon F6, I've learned that it was announced on the same day as the Nikon D2X, also mentioned above: September 16, 2004, and that while the Nikon F5 was Nikon's flagship film camera for professionals, the Nikon F6 was aimed at serious amateur photographers instead, with the D2X being the alternative Nikon offered to professional photographers at the time.

The characteristic of having a removable pentaprism was shared with the Exakta cameras for which pentaprisms were available, and with the Praktica fx-2, and fx-3, and the later Praktica VLC, VLC 2, and VLC 3 as well as the Praktina fx and the Praktina IIa, some of which we met earlier.

Also, the impossibly rare Zunowflex camera from 1958 had a removable pentaprism. While the Pentacon F from 1956 introduced the internally-coupled automatic diaphragm, and the Asahiflex II rom 1954 introduced the instant-return mirror, these were still not common features in 1958, but the Zunowflex included them both. Unfortunately, the camera was plagued by quality control issues which were what led to its being discontinued.

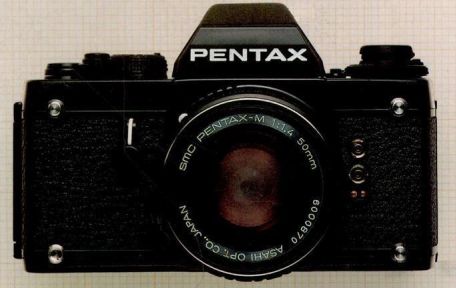

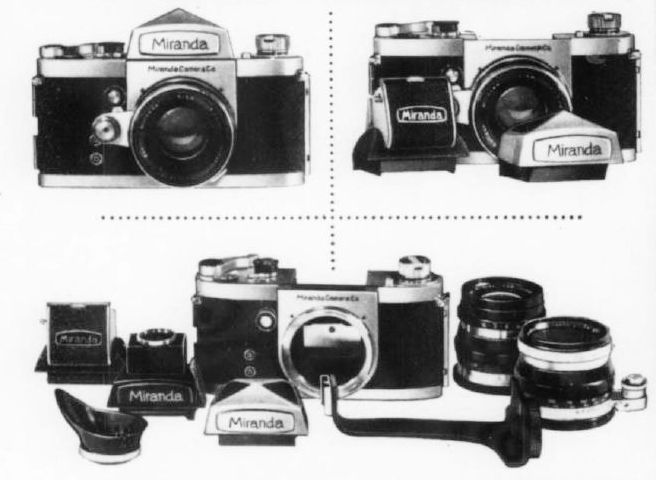

But Nikon wasn't the only later camera maker to offer this feature in their most versatile cameras. Interchangeable viefinders were also a characteristic of the Canon F-1 (and also the later New Canon F-1), the Minolta XK (or the Minolta XM outside the United States), and the Pentax LX. Also, many Miranda SLR cameras had removable viewfinders. And so did the Alps Ambiflex, which also used a leaf shutter instead of a focal plane shutter.

Pictured below are the Praktica VLC, the Pentax LX, the New Canon F-1, and the Minolta XK from among the cameras having this elite feature.

This feature was important enough that it was also sometimes mentioned in advertising for cameras from many manufacturers, not just Nikon. Here, for example, is an image from an advertisement for the Praktisix camera, a medium format SLR made by Pentacon, the makers of the Praktica line of 35mm SLRs:

showing the camera, some lenses available for it, the pentaprism finder (with the waist-level finder on the camera instead), and several focusing screens.

And shown at left is a picture from an advertisement for the Minolta XK, which we saw above, showing the assortment of accessories available for it - including alternative pentaprisms and focusing screens.

And at right is an image from an advertisement showing the versatility of an early camera from Miranda - again, including the ability to swap out the pentaprism.

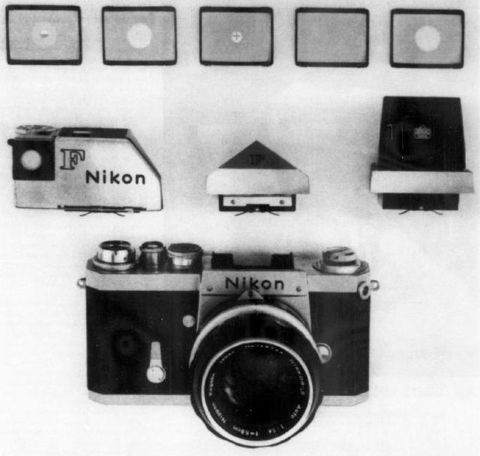

And here's a picture from an advertisement for the Nikon F,

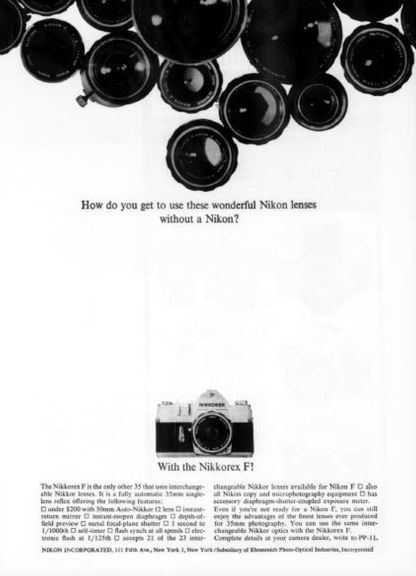

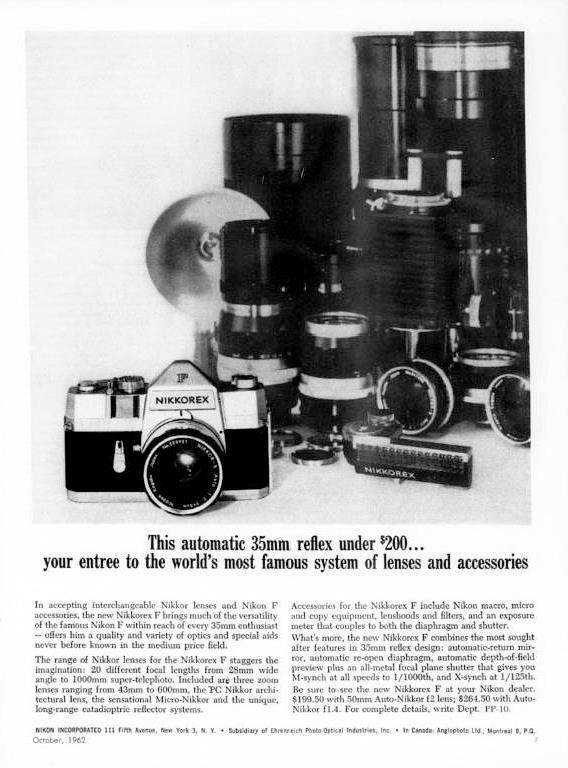

which just shows that choices are available for the focusing screen and finder. (The wide assortment of Nikon lenses, and their quality, was also mentioned in an advertisement for the Nikkorex F camera that appeared in the same issue of the same magazine as the advertisement this image came from, as it happens: that advertisement is shown at right.)

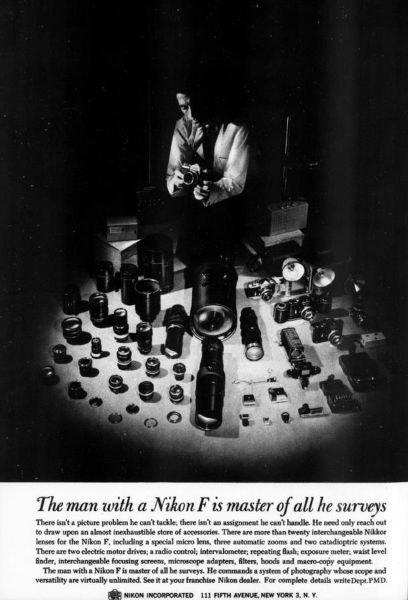

While other brands of camera also ran advertisements showing the range of lenses and accessories available for them, this was particularly significant for Nikon as a selling point for the Nikon F, and thus over the years several different advertisements of this nature appeared for that camera; another one appears at left.

The large lens at the top of the assortment of items is a mirror lens. Despite the corrector plate being convex on the outside, since the secondary mirror is mounted in a plug on the corrector plate rather than being a silvered spot on it, I suspect it is still a Maksutov-Cassegrain lens rather than a Maksutov-Gregorian... and I also suspect that for the excellent reason that a Maksutov-Gregorian telescope is an erecting telescope, and so a camera lens of that type would lead to upside-down images on the film, which one could live with, but also upside-down images in the reflex viewfinder of an SLR.

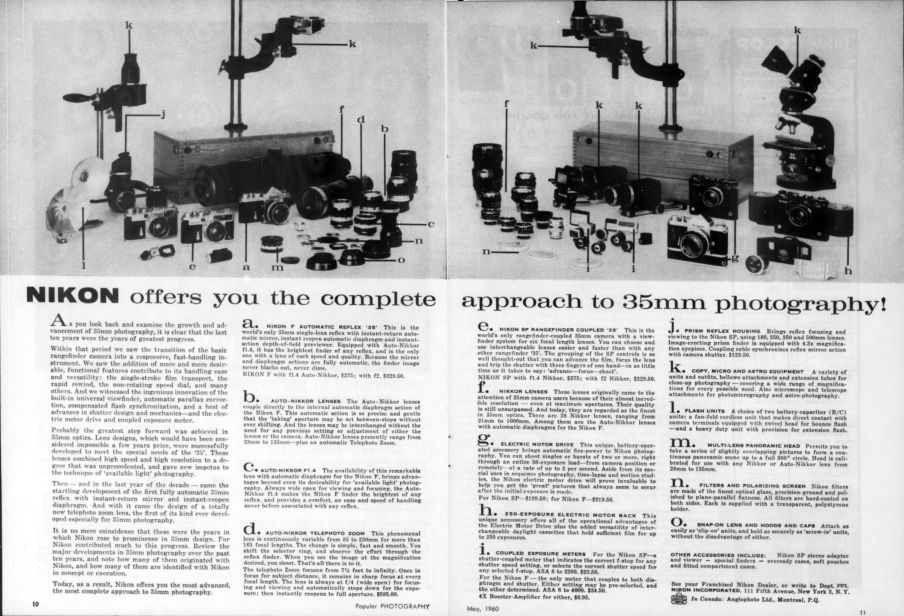

The advertisement below ran in 1960, shortly after the introduction of the Nikon F in 1959,

and shows how Nikon made sure that a wide assortment of accessories, sufficient to make full use of the potential of the Nikon F as a "system camera", would be available at its inception. But there was time enough since the camera's introduction for the illustration in this advertisement to reflect some changes: item i in the illustration, the coupled exposure meter, is an example of the third variant of that exposure meter rather than the first.

Pictured at right is another advertisement showing how the Nikkorex F has access to the large assortment of lenses for the Nikon F, as well as at least some of the other accessories for it. A flashbulb unit is shown, and so is a version of the Selenium cell exposure meter, but bearing the name "Nikkorex" instead of "Nikon" along the bottom.

Pictured at left is the Nikkormat FT from 1965. As an advertisement for this camera notes, it was "Developed by Nikon, built by Nikon, and designed by Nikon for use with Nikon lenses". But then, what else would you expect? It included a built-in through-the-lens metering system, and was, as of course one would expect, sold at a lower price than the professional F-series cameras from Nikon.

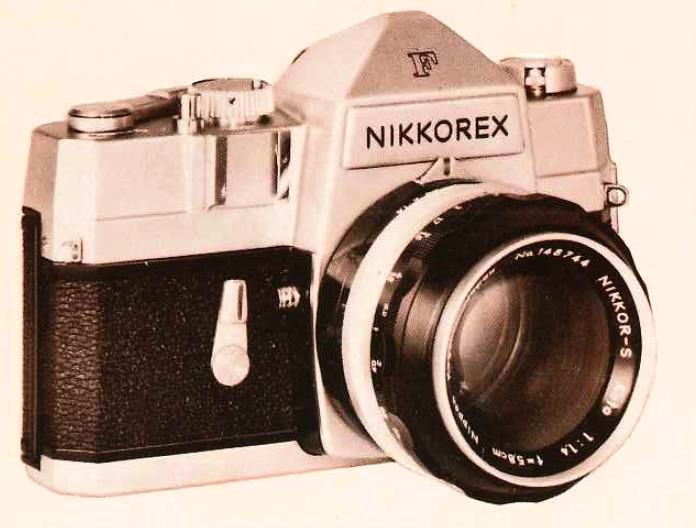

I mean, who else would you expect to be making Nikon cameras? Mamiya? Well, back in 1962, when Nikon held fast to its previous decision that it should be expanding the market for their lenses by offering a less expensive alternative to their professional Nikon F camera that could also use them, I had thought they wanted to get their feet wet, setting up new manufacturing facilities that were oriented towards controlling costs while still maintaining quality - but not to the same uncompromising level as with their professional cameras - seemed like too large a step to take right away; but given the fact that this camera was preceded by the Nikkorex-35, apparently the motivation was instead the desire for a fresh start.

And so they commissioned Mamiya to make the Nikkorex F camera for them to their specifications.

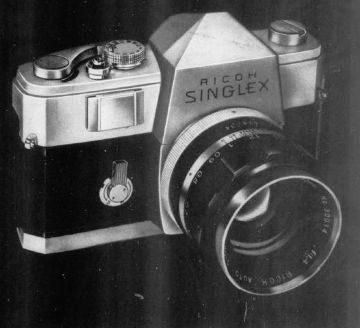

Later on, after Nikon discontinued the Nikkorex F, the same camera continued to be made for sale as the Ricoh Singlex camera, pictured at left, and the Sears SL11 camera. Both of these cameras did have the Nikon F lens mount, so Mamiya had retained the rights to use that. Ricoh later used the Singlex name for several cameras of its own design, which used the standard M42 screw mount.

The first accounts of this I read stated that Mamiya continued to manufacture the cameras itself for Ricoh, but I later encountered accounts which seem more credible which state that Mamiya sold the tooling to Ricoh, with Ricoh then making the camera, and also making it for Sears to sell as the SL11.

Before the Nikkorex F, Nikon did make an attempt at producing a less-expensive SLR. That camera was the Nikkorex 35, released in 1960, pictured at left. Although the camera was made by Nikon itself, a portion of its manufacture was outsourced, and there were several problems with the camera. It was attempted to remedy the issues with the Nikkorex 35-2, released in 1962, pictured at right. As this version of the camera used a different shutter mechanism, the camera had to be almost completely redesigned. While the issues with the original version were corrected in this camera, its sales suffered due to the reputation created by its predecessor.

One interesting characteristic of the Nikkorex 35 is that it used a Porro prism assembly instead of a pentaprism, in order to save weight. Also significant is that the Nikkorex 35 did not use Nikkor lenses, for the simple reason that the cameras in that line did not have interchangeable lenses, unlike the Nikkorex F and the subsequent Nikkormat.

There was also a Nikkorex 35 Zoom, illustrated at right, from early 1963, which had a zoom lens as its built-in lens for greater versatility, thus anticipating what are now known as "bridge cameras"; it will be mentioned again later.

Incidentally, it should be noted that except for the horizontal lines and the word "Nikkorex" on the nameplate, the nameplate on the Nikkorex 35-2 and on the Nikkorex 35 Zoom was transparent, it being made from clear plastic. These cameras still had a selenium cell for a light meter, just less obvious behind the nameplate.

Incidentally, Nikon was not the only company that had cameras which it sold under its own name manufactured for it by Mamiya. The first SLR sold by the American camera company Argus was also made by Mamiya. An image of that camera is shown at left.

The usual lens that came with it was an f/1.7 Argus-Sekor, so it can hardly be said that the fact that this camera was made by Mamiya was a closely-guarded secret.