As has been mentioned, and as we will see later in more detail, Nikon encountered serious problems as a result of attempting to make cameras that advanced the film by seven perforations after each exposure, instead of following the eight-perforation standard established by Leica.

How did owners of Stereo Realist cameras manage to get their films developed, since those cameras used a five-perforation frame size? Presumably it helped that Kodak itself made a stereo camera that was compatible with the Stereo Realist. But the Stereo Realist format wasn't the only format for 35mm stereo cameras: European makers of stereo cameras often used a format where each frame did use seven perforations, with the images in one stereo pair being separated by one image, rather than two images, from other stereo pairs. Does that mean it was unfortunate the American occupation authorities didn't allow Nikon to export the Nikon I to Europe, because its pictures could presumably have been developed there? Apparently, though, while Iloca and perhaps a few other European companies made stereo cameras in this format, they quickly converted to the Stereo Realist format as well, so the capacity to process 7-perf films apparently would have died out in Europe as well.

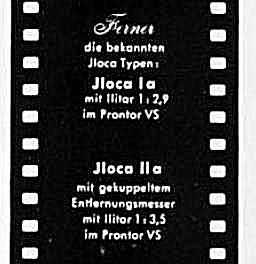

Oh, and speaking of Iloca. The camera's logo used a cursive I, and so in that logo, the camera's name looked like "Jloca". And so sometimes people have misspelled their name as Jloca. Or so I've heard. However, in looking both at advertisements for their cameras (an example being shown at right), and in manuals for their cameras, I've seen that the company itself rendered its name as "Jloca" in conventional typefaces in regular text as well, presumably for consistency with the logo? Given that, I can hardly consider the alleged misspelling culpable; maybe their name really is Jloca if they spell it that way themselves.

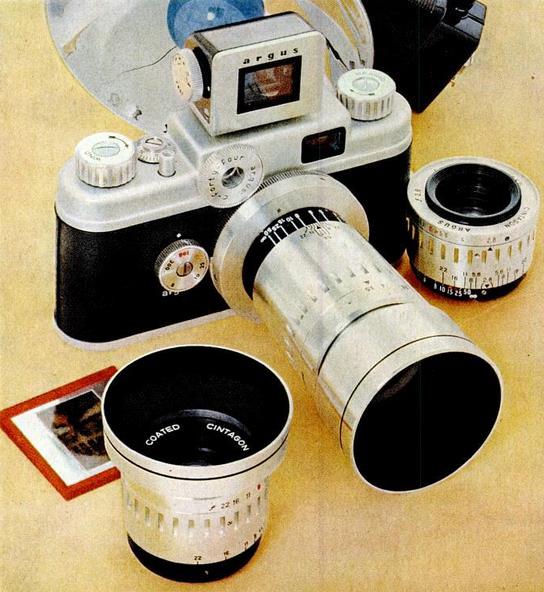

At left is shown the Argus Candid camera, and at right the Argus Miniature camera; both appear to simply be the names originally used for what was later termed the Argus Model A camera. This camera came with an f/4.5 lens, and sold for $12.50 in the United States when it was introduced in 1936

A few years later, in 1939, the Argus Model M, with an f/6.3 lens, sold for only $7.50, and the price of the Argus Model A, as it then became known, went down to $10.00.

The Argus Model A camera is credited for creating much of the popularity of the 35mm still picture film format in the United States, being more affordable than a Kodak Retina, at $57.50, or a Leica.

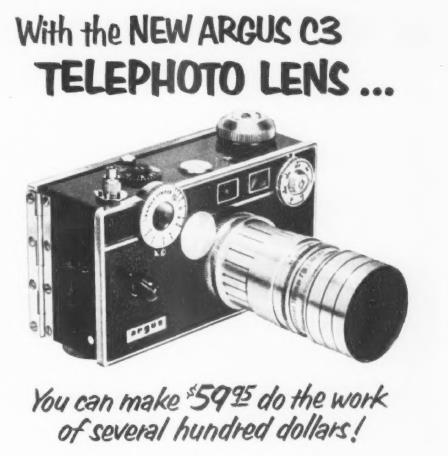

Also in 1939, Argus offered the C3, also a budget-priced camera for its day, selling for $30.00 in 1939, and $69.50 in 1953, which proved very popular in the United States as well. It did have interchangeable lenses, and so one American photographer, Tony Vaccaro, used it for his photography of World War II.

Here's part of an advertisement for the Argus C3 and for a telephoto lens available for it showing that it was very much a selling point of the camera that it was a 35mm rangefinder camera with interchangeable lenses offered at a much lower price than other well-known cameras with those characteristics.

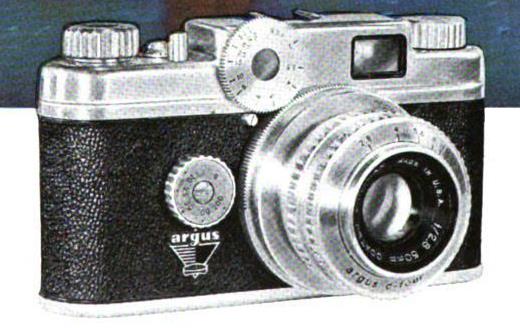

By 1951, along came the Argus C-4, for $99.50, pictured at right, which certainly looked like a real rangefinder camera; by 1954, the price had gone down to $84.50.

Unlike the case of the C-3, however, the lens on the C-4 was not interchangeable. However, Geiss-America, importers of Lithagon lenses from Enna-Werk, which we will encounter later as an early maker of zoom lenses, were willing to remedy that lack so they could sell those lenses to Argus C-4 owners; they had a kit that added an interchangeable lens mount to a C-4 that a dealer could inexpensively install.

Their advertisement is shown at right; note that an auxilliary finder is provided for the camera's accessory shoe, the "Zoom-Vue" viefinder, available separately for $16.95.

This is significant since the fact that they chose the Argus C-4 as the camera to offer their lenses for in this manner shows that the Argus C-4 was a rangefinder camera of reasonably good quality, but without interchangeable lenses, that was in a lot of people's hands - thus confirming the important role of Argus in popularizing the 35mm film format.

It is also the case, though, that Enna-Werk was one of the principal suppliers of lenses for the earlier Argus C-3 camera, so a relationship with Argus and/or familiarity with their cameras likely played a role.

That was also more formally remedied by the Argus C-44. Unfortunately, the lens mount was differe from that of the C-3. In fact, the bayonet lens mount of the C-44 was one of the most significant drawbacks of the camera, as it was difficult and awkward to change lenses on it; one had to set the focus on the lens to infinity before removing or installing it! Actually, criticizing the Argus C-44 for that may be unfair; according to the manual for the Nikon S-2, this also had to be done when changing lenses on it!

However, despite being budget-priced cameras, the C-4 and C-44 were of reasonably good quality, and have been described as the best quality cameras Argus had ever made itself.

Incidentally, the C-44 did not have a focal-plane shutter, like the Kodak Retina Reflex S camera and later models, it had a conventional shutter positioned behind the lens on the camera body.

At left is an Argus C-44 pictured with a coupled Selenium cell exposure meter, as well as an auxilliary viewfinder allowing one to frame shots for three different focal lengths of interchangeable lens. A telephoto lens is shown attached, illustrating that the camera has interchangeable lenses.

At right is pictured another Argus C-44, this time with a continuously variable auxilliary viewfinder.

At right is an image of another Argus C-44, this time with a normal lens instead of a telephoto. However, this wasn't the standard f/2.8 normal lens, it was the more expensive f/1.9 normal lens.

While f/1.9 may not sound like much, Erich Salomon did his famous available light photography with f/2 and f/1.8 lenses on his Ermanox, and in 1956 or thereabouts 35mm film would have had faster emulsions than those of the glass plates Erich Salomon used. So it's not at all an exaggeration to claim that an f/1.9 lens is usable for available light photography, as the advertisement in which this image appeared did.

What does concern me in the picture, though, is that instead of showing the same coupled meter as we saw in one of the images above, this camera is shown with an exposure meter in the accessory shoe. It suggests one would have to get one meter to use with normal lenses, and then a different meter to use with a telephoto lens, which hardly makes any sense!

And one also has to give Argus points for having manufactured the C-44 itself; Kodak, which also made popularly priced cameras for the masses, bought a German camera company in order to offer their Retina line of cameras.

Actually, that's not entirely a fair criticism. At left is an image of the Kodak Signet 80, a 35mm camera from another line which Kodak made domestically which did also have interchangeable lenses. Unlike either the Argus C-44 or the Argus C-3, it had a built-in Selenium cell exposure meter, and was more expensive at a suggested retail price of $129.50, so I presume it wasn't positioned as direct competition to those two products, but it is an example showing that Kodak did make comparable products in that area.

Since Kodak's only other American-made rangefinder 35mm camera that had interchangeable lenses was the Kodak Ektra (which we will see was a very expensive camera), even if the Signet 80 wasn't positioned to compete directly with the Argus C-44, it, and, of course the Retina which Kodak made in Germany (at least the Retina IIIS), were all the competition for it that Kodak had.

Both the Signet 80 and the Argus C-44 ceased production in 1962. It was only the Signet 80, the last model in the Signet line, that had interchangeable lenses.

And that the Argus C-44 was a quality camera is not to be marvelled at; after all, consumers would expect even an inexpensive camera to work, and to work reliably. Had Argus cameras not met that standard, they would not have been so successful as to sell more 35mm cameras than Kodak in their heyday. The following Cintagon lenses were the ones available for the C-44:

35mm f/4.5 50mm f/2.8 50mm f/1.9 100mm f/3.5

A modest assortment; one could get something with a wider aperture than the standard f/2.8 offered with the C-4, but it was an f/1.9, not an f/1.4. Presumably, people who could afford an f/1.4 lens could also afford a Nikon S-2, and would buy one.

According to the manual for the Nikon S-2, the available lens assortment for it, still quite modest compared to what would become available for the Nikon F, was the following:

25mm f/4 28mm f/3.5 35mm f/3.5 35mm f/2.5 50mm f/2 50mm f/1.4 85mm f/1.5 105mm f/2.5 135mm f/3.5

and this is part of where the distinction lies between a budget-priced camera and one that is acclaimed as one of the finest cameras, a wider assortment of lenses which is made up of lenses with wider apertures.

The assortment of lenses offered for the Kodak Signet 80 was even more limited:

35mm f/3.5 50mm f/2.8 90mm f/4

A telephoto and a wide-angle lens were available, but there was no option to get a faster lens than the standard normal lens.

In the case of the Retina IIIS, however, the assortment of lenses was fairly wide, with both Rodenstock and Schneider making lenses for the camera:

28mm f/4 30mm f/2.8 35mm f/4 35mm f/2.8 50mm f/2.8 50mm f/1.9 85mm f/4 135mm f/4 200mm f/4.8

But with f/2.8 and f/1.9 being the apertures available in 50mm, it's clear that the Retina IIIS is in the same league as the Argus C-44, even if ahead in some ways, while the Signet 80 is left behind, despite being more expensive than the C-44.

How about the Argus C-3? It wasn't until 1953 that a wide-angle lens was offered for the series it belonged to, while a telephoto lens was available much earlier - a 75mm f/5.6 lens first advertised in 1939 for the Argus C-2 and C-3, sold through Argus but made by Bausch and Lomb. The only normal lens readily available for the Argus C-3 was an f/3.5 50mm lens. Enna-Werk made a number of Lithagon lenses for the Argus C-3, and they did make a 53mm f/2.0 lens for it, but only a very small number of them, which suggests to me that they were not made available for sale. That may not be the case, however; it may just be that there was no interest in an expensive lenses from the budget-minded owners of the inexpensive Argus C-3.

I find the claim that so few were made difficult to accept; what with Enna-Werk being a third-party lens manufacturer, one possibility that I would find plausible is that perhaps they made many 53mm f/2 lenses, but because of demand, put Leica mounts, or mounts for other cameras that weren't Argus C-3s, on them because that's were the demand was - and had they recieved more orders for that lens in the Argus C-3 version, more would have existed. In a situation like that, I could believe that they designed and made a 53mm f/2 lens... and only made a handful of those lenses with an Argus C-33 mount, because then there would have been a normal-sized production run for most of the lens. I haven't found evidence of any other Enna-Werk 53mm f/2.0 lenses for rangefinders yet, though; the only other 53mm f/2.0 lens I've found after searching is one for a Topcon SLR. However, since Enna-Werk is located in Munich, Germany, there is also the possibility that the lens was simply a victim of bad timing, if it originally came out before World War II.

The two different auxilliary viewfinders shown in the first two images of the Argus C-44 camera above highlight the importance of having some way to accurately frame shots for a rangefinder camera with interchangeable lenses, as does the Zoom-View viewfinder for the Lithagon lenses shown in the advertisement above; later, we will discuss the Nikon SP rangefinder camera, which took a different approach to addressing this important issue: in addition to the rangefinder having border lines visible for some of the lenses available, there was a secondary viewfinder built into the camera body with a wider field of view with border lines to show the field of view for the remaining lenses available.

But Leica tried yet another approach to this issue:

The image above shows, on the left, a 35mm lens for the Leica M-2 camera which has, built into the lens, supplementary lenses above it for the camera's rangefinder that will convert it to showing the field of view for the 35mm wide angle lens, thus providing the best possible accomodation for that alternate focal length.

Of course, it has the drawback of making the lens more bulky and possibly fragile as well, which perhaps is why Leica did not continue to make its interchangeable lenses in this way.

On the right in the image, though, is a 50mm lens. Why would a normal lens, replacing the lens the field of view of which for which the rangefinder was designed, need to place supplementary lenses in front of the rangefinder? There is an explanation: the 50mm lens shown in the image above is a macro lens, allowing photographs to be taken of subjects closer to the camera than usual, and so modifications to how the rangefinder worked were required to accomodate that.

Incidentally, I found out that the Argus C-4 came up in a debate over the political issue of tariff policy in the 1950s:

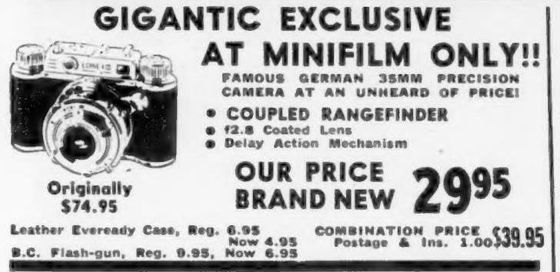

On the left is part of a full-page advertisement by Minifilm which mentions many cameras and other items of photographic equipment which may have been what Robert E. Lewis, President of the Argus Camera company was referring to in his testimony before the House Ways and Means committee in 1955, where he was arguing that American camera companies like his own were in need of tariff protection to survive, the Argus C-4, having similar specifications, having the much higher price of $84.50. However, as we can see from the advertisement, the leather case and the flash gun were not included in the $29.95 price, as was claimed for the example camera that was threatening the survival of the American-made C-4, so perhaps a different advertisement, offering an even cheaper camera from Germany with an f/2.8 lens, escaped my notice when I found this one and no others offering quite as low a price.

Charles H. Percy, the President of Bell and Howell, on the other hand, argued that reciprocal reductions in tariffs were what was needed because European tariffs were preventing American camera makers from exporting to Europe.

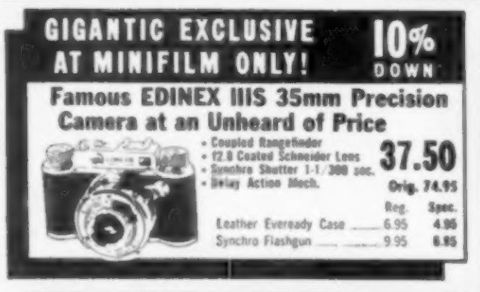

As we can see at right, though, the price went up when Minifilm was able to reveal the name of the camera in question.

And indeed the Edinex was made by Wirgin, makers of Edixa cameras.

When the Edinex IIIS was originally offered for sale, its price - or at least one price for which it was offered by one vendor - was $59.50; shown at left is a better picture from an advertisement for it from back then, although the picture may have been of the nearly identical Edinex III (which was more expensive, as it had additional features).

As these pages deal primarily with the 35mm single-lens reflex camera, later on we will of course encounter Kodak's camera of that type, the Retina reflex. This camera was built in Germany, by a German division of Kodak resulting from its purchase of a German camera manufacturer.

Kodak's first camera with the Retina name, introduced in December 1934, is of immense historical significance for another reason. Along with this camera, Kodak introduced the 135 film cartridge. This was designed to be compatible with the spools used for 35mm film in the original Leica camera, and the other cameras which were compatible with it. Until the 135 cartridge was introduced, since 35mm film did not include a backing paper, 35mm cameras had to be loaded with film in the dark.

The story of how all this came about due to Kodak's acquisition of Nagel Kamerawerk is recounted here.

At left is shown a detail from an advertisement from 1935 featuring several of Kodak's cameras of the time, which refers to daylight-loading cartridges as a feature of the original Retina viewfinder camera.

At the time of its introduction, the Kodak Retina was Kodak's only still picture camera that used 35mm film. As it was manufactured in Germany, and storm clouds were gathering in that direction, Kodak saw the necessity of remedying that deficiency, and it proceeded to develop four 35mm cameras for domestic production.

The simplest and lowest-priced one was the Kodak 35. It had a viewfinder, and its fixed lens could be focused. A version of the Kodak 35 with a rangefinder added was later also made, as shown at left.

There was the Kodak Pony 135, which was adapted from the Kodak Pony 828. As 828 film was 35mm wide, but on spools with paper on the back, like 620 film and 127 film, it was relatively simple to modify the design to use 35mm film instead. A later version of that camera is shown at right.

Then there was the Kodak Signet series. Only the final model in that series, the Kodak Signet 80, which is shown above on this page, had interchangeable lenses, but one of the earlier models, the Kodak Signet 35, shown at left, also had a rangefinder instead of a viewfinder.

An important Kodak rangefinder camera without interchangeable lenses that used 620 roll film was the Kodak Medalist. This camera was even selected by the U.S. Navy as one of the film cameras to have as standard equipment on its vessels, on the basis that it was the best camera for use by someone without specialized training in photography.

It took photographs in 6x9 cm format, so it hd the same 3:2 aspect ratio as a typical 35mm camera. Its built-in lens was an f/3.5 100mm lens. For a 90 mm by 60 mm image area, this would be equivalent to a 40mm lens used with the 36 mm by 24 mm image area of a 35mm camera.

Then there was the Kodak Ektra, shown at right. This camera began production in 1941, and then returned to manufacture for civilian sale in 1948. It was a rangefinder camera with interchangeable lenses. Unfortunately, it sold for $235 in 1941, and apparently its 1948 price was even higher. Which, in 1948, made it more expensive than a Leica, which camera by that time was available in the U.S. once again. Of course, during wartime, simply having the domestic capability of making a quality 35mm camera, whatever the price, was of importance.

The image below shows the line-up of Ektar lenses Kodak made available for the Ektra:

The lenses, as shown from left to right, are:

50mm f/1.9 50mm f/3.5 35mm f/3.3 90mm f/3.5 135mm f/3.8 153mm f/4.5

The 50mm lenses compare to those offered for the Argus C-44, instead of those offered for the Nikon S-2, but this line-up of lenses is from 1941, so advancing technology is what meant that in the 1950s, cheaper cameras offered lenses comparable to those offered with the most expensive cameras in 1941.

The 50mm f/1.9 lens was a seven-element Double Gauss lens, while the 50mm f/3.5 lens was a Tessar, and the 90mm f/3.5 lens was a Cooke Triplet.

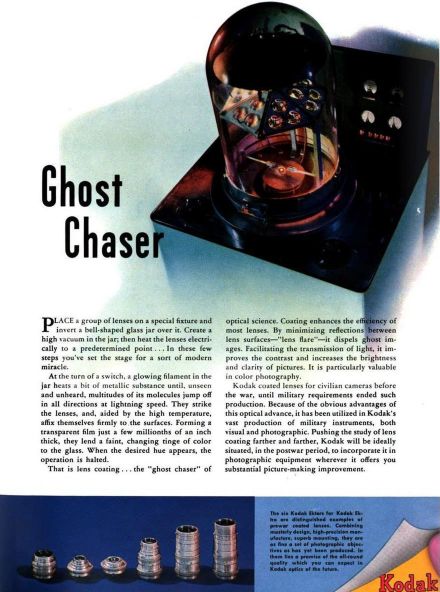

Aside from this being the origin of the Ektar name, which Kodak later applied to many other lenses, the lenses provided for the Ektra are historically important as being the first coated lenses offered with a camera. After 1946, these lenses were referred to as being "Lumenized", to convey the idea that coated lenses transmit more light.

The lenses sold for the Ektra in the U.S. before Pearl Harbor were indeed coated, although some prototypes were not, so even if that feature hadn't yet gotten a trademark or become widely advertised, lens coating itself wasn't a German military secret that the Allies discovered from captured equipment, even if the Germans made advances in that area which they did keep secret and which the Allies did discover in this fashion. The Kodak advertisement shown at right, from 1945, specifically notes that Kodak had been coating lenses for civilian production before the war.

Coating lenses to improve light transmission was first discovered by Lord Rayleigh in 1886; in 1935, Alexander Smakula at Zeiss patented one form of lens coating.

One of the most common materials used for anti-reflection coatings for lenses was magnesium fluoride, since its index of refraction is close to being intermediate between that of glass and air, so that the air-coating surface and the coating-glass surface each reflect less light than a plain air-glass surface. In addition, the thickness of the coating is chosen so that the two nearly equal reflections tend to cancel each other out through destructive interference. A single magnesium fluoride coating being the least expensive kind of coating, it is still found on inexpensive optics today, where it gives a deep blue color to the reduced reflections from the lens that still remain.

Before lens coating was widely applied, lenses were often designed to have as many cemented surfaces instead of air gaps between elements as possible, so as to minimize spurious reflections.

Because lens coatings are fragile, some lenses did not include coatings on their front and back surfaces, but only on internal surfaces, where they are more important; on the front surface, light is only lost; on internal surfaces, spurious reflections can show up in the final image. In the very early days of coated lenses, calcium fluoride was used as the coating material instead of magnesium fluoride, and that material was particularly soft; magnesium fluoride was considered suitable for use on the external surfaces, even if special care had to be taken when cleaning such coated lenses, but calcium fluoride was not.