Before photography existed, artists used the camera obscura as a means of tracing scenes from nature in two dimensions. A converging lens of some sort allowed one to have more light than a pinhole camera could provide, since now the rays of light coming from a point in the scene being viewed that go through a wider opening could be brought to a focus on the screen by the lens.

William Hyde Wollaston, who discovered the elements palladium and rhodium, also invented, in 1812, for the camera obscura, before photography existed, the first lens that could be considered as specifically applicable to photography; he discovered that a deep meniscus lens, placed behind the aperture, would produce an image that was sharp enough to be useful over a larger angular field than an equivalent plain biconvex lens of the same focal length would provide.

Lenses themselves are, of course, far older even than their use with the camera obscura. Ptolemy described the magnifying glass. Reading glasses, which quickly became used as corrective eyeglasses for far-sightedness, were invented somewhere in northern Italy in the 13th century, and eyeglasses with concave lenses to correct for near-sightedness came into use in the 15th century. And the invention of the telescope by Jan Lippershey took place in 1608.

When the Daguerrotype was first invented, it wasn't practical to use it for portraits, at least of living subjects. Bromine was used to improve the sensitivity of the plates, and that, along with the Petzval portrait lens, solved this issue.

Joseph Petzval originated the concept of the Petzval sum in optics. This embodied the fact that it was easier to calculate curvature of field than other aberrations in lens designs. At the time he lived, however, it wasn't possible to use this knowledge to design lenses that had flat fields, because the only optical glasses that were available were plain crown and flint glasses. The flint glasses all had a higher index of refraction than the crown glasses. (This, of course, was only a problem if you also cared about chromatic aberration.)

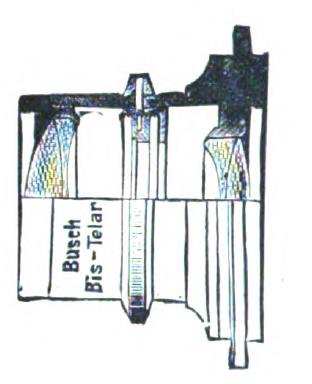

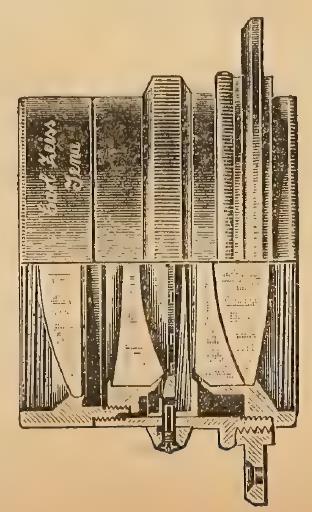

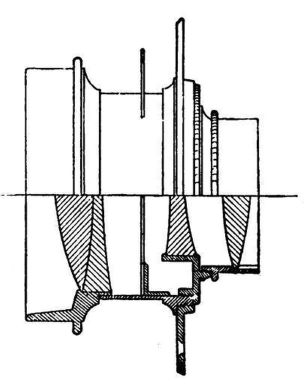

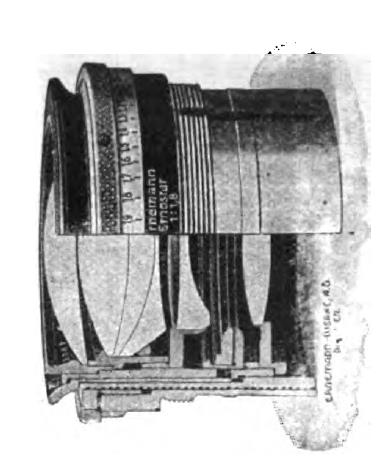

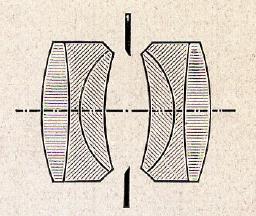

So, in the Petzval portrait lens, shown at right, he cheated. He introduced astigmatism into the lens, which separated two focal planes, the tangential and sagittal ones, so that although the lens had curvature of field, one of those two fields could be flat and coincide with the film, producing a sharp image, even if its contrast was lower.

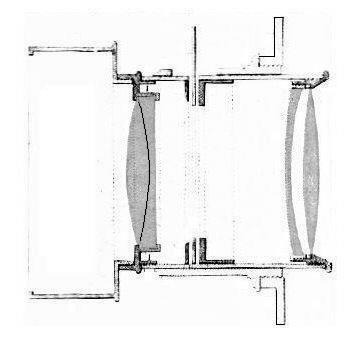

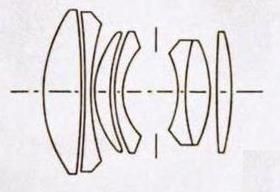

When high-index crown glasses later became available, Dennis Taylor, in 1893, invented the Cooke Triplet lens, illustrated at left. This lens corrected chromatic aberration and all five of the third-order Seidel aberrations. Thus, while it still did not produce perfect images beyond a fairly modest aperture, since there are also higher-order aberrations, it was an immense step forward in lens design, as well as a very useful lens in its own right. Replacing the rear positive element with an achromat led eventually to an effective aperture as high as f/2.8 in the Zeiss Tessar lens, designed by Paul Rudolph in 1902.

Before the Cooke Triplet was possible, lenses were designed with more modest goals, and there are two terms used in the description of such lenses that should be defined here. An aplanat is a lens corrected for spherical aberration and coma; an anastigmat is one corrected for spherical aberration, coma, and astigmatism.

The remaining two Seidel aberrations, curvature of field and distortion, have to do with the location and shape of the image formed by the lens, and so a lens only needs to be an anastigmat to form a sharp image, even if that sharp image is not really of the kind one wanted.

And, as the Petzval lens demonstrates, even an aplanat yields sharp images - two of them, both with low contrast. This is why these two partial ways of addressing aberrations were of interest.

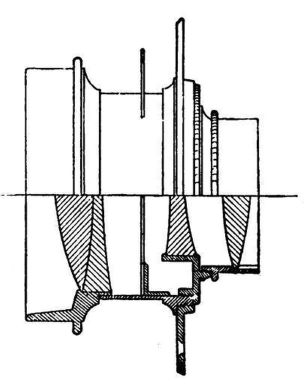

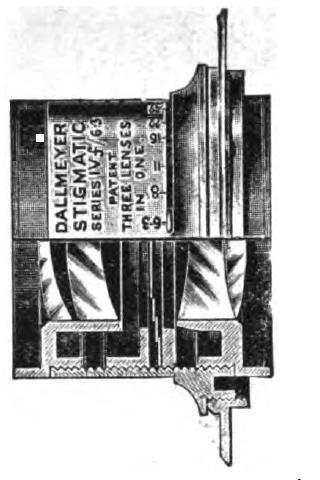

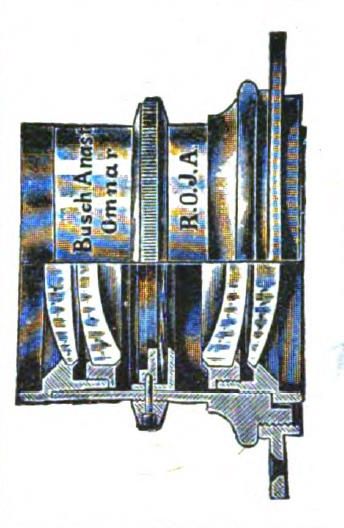

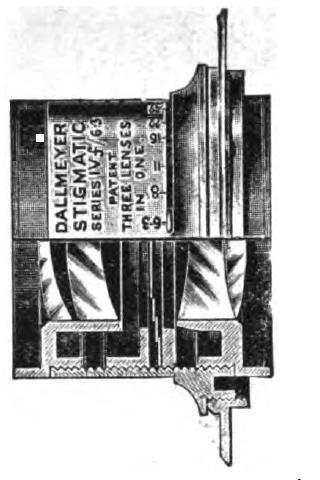

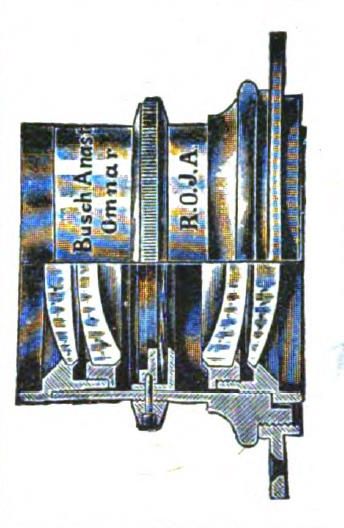

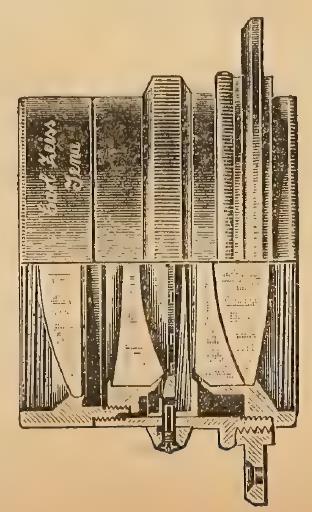

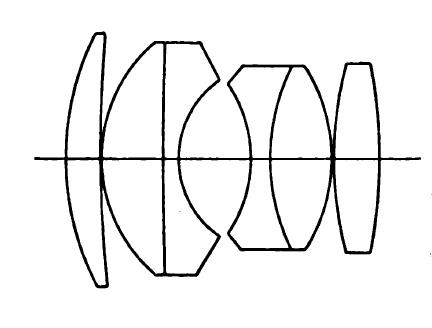

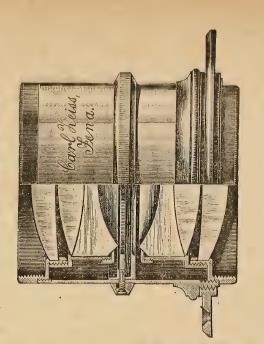

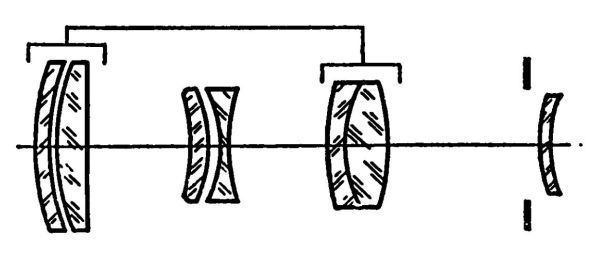

Here are old illustrations of some old lenses of interest.

Shown above are the following lenses:

|

The image above is from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 International License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is ---hoep. |

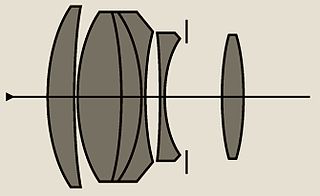

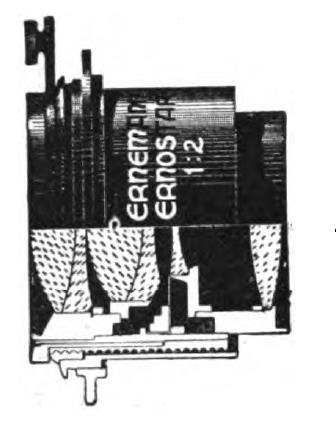

In 1920, Horace William Lee invented the Opic lens, which was the first of the modern Double Gauss lenses. The Double Gauss principle was known earlier, for example in an Alvan G. Clark lens from 1890, and the Planar, designed by Paul Rudolph in 1896, but it wasn't until the Opic that the full potential of this design became visible. The f/2 lens used on the Ermanox later was of a different type of design, and was more successful, but not only did other designers pick up on the Double Gauss design, such as the Xenon from Schneider by A. Tronnier in 1925, and the Biotar from Zeiss by W. Merté in 1927 (shown at left is the layout of a later Biotar lens, which reached f/1.4); but in 1931 Lee enjoyed financial success of his own by designing the Speed Panchro lens, an f/2 Double Gauss lens that was for many years the most popular type of lens used by film makers in Hollywood. Also, earlier, in 1927, he devised an improved Double Gauss lens; while the patent on that lens, U.S. Patent 1,779,257, only attributes to it a maximum aperture of f/1.5, the version ultimately offered for sale, the Ultra Panchro, reached f/1.4.

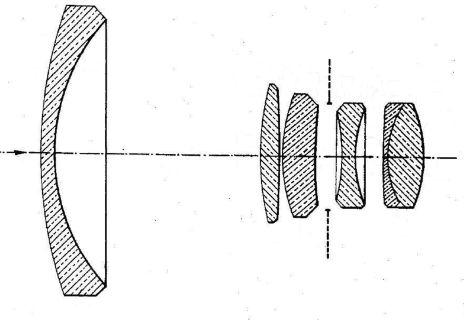

The layout of the components in the f/1.8 version of the Ernostar is shown at right.

If the 50mm normal lens on a 35mm camera has an aperture as wide as f/1.4, as the premium lenses for high-quality cameras often did, very likely it is of the Double Gauss design, although some such lenses have been based on the Ernostar or the related Sonnar instead.

At left is a typical modern Double Gauss design; it improves on the basic design by splitting the final convex element into two convex elements with less curvature, thus reducing the amount of spherical aberration to correct. The Speedic lens applied the same improvement to the Cooke Triplet.

At left is another modern Double Gauss design, the Aero Ektar from Kodak; here the improvement that is made is instead replacing the final convex element with an achromat, thus decreasing its contribution to chromatic aberration. This is the same improvement that was applied to the Cooke Triplet by the Tessar.

And this f/2 Summicron is another example of a modern Double Gauss design. Here, the front convex element is turned into an achromat, and instead of being cemented, it is split by a tiny air gap, and the first meniscus group is also split by a tiny air gap.

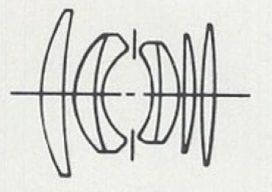

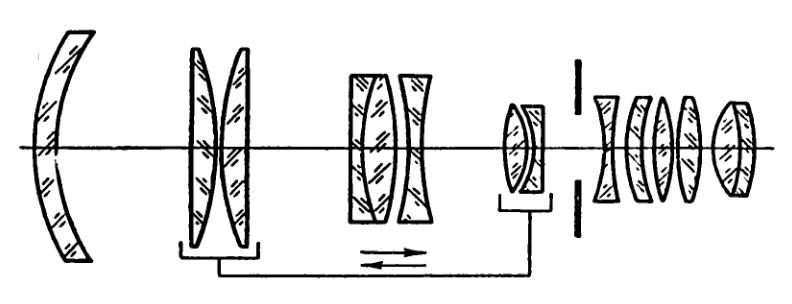

Here are some old images of lenses related to what has been written above:

The lenses shown above are:

An important design feature of the Planar is the "buried surface". The crown and flint glasses used in the elements which formed the two compound menisci in the interior of the lens were chosen to have as nearly the same index of refraction as possible. In this way, the overall shape of the meniscus could be chosen to correct for spherical aberration, and the boundary between the convex crown element and the concave flint element of the meniscus could be chosen to correct for chromatic aberration, without an interaction between those choices complicating matters.

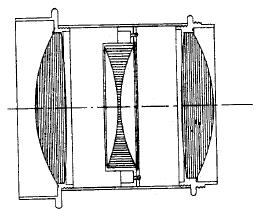

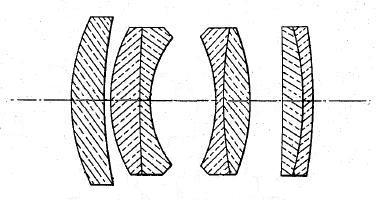

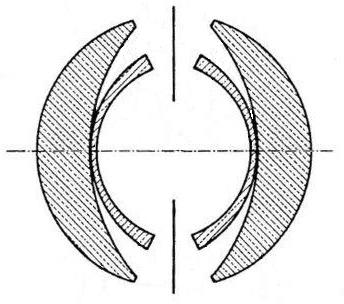

The principle behind the Double Gauss lens, that some aberrations may be corrected by making a lens symmetric, so each half of the lens can be designed to correct only the remaining aberrations, was used in other lens designs as well. One example of this is the Dagor, shown at left; each individual half was corrected for spherical aberration and chromatic aberration, as well as astigmatism and curvature of field, but repeating the halves symmetrically was what corrected coma. The Dagor was also advertised as an anastigmat; but then, so was the Cooke Triplet, even though both lenses corrected for all five of the third-order Seidel aberrations.

The telephoto lens and the wide-angle lens were other important advances in lens design, which gave photographers greater flexibility; a very popular type of lens today, although it requires more elements than an ordinary lens to work properly, is, of course, the Zoom lens.

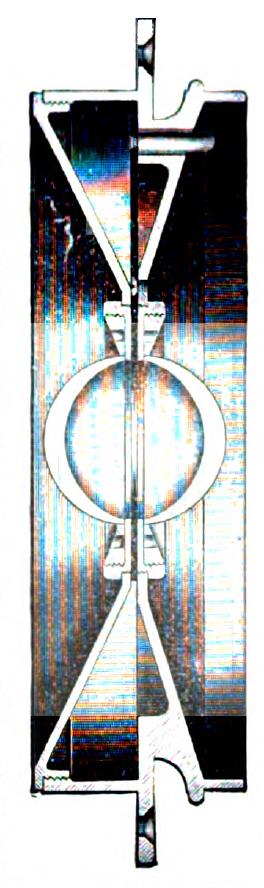

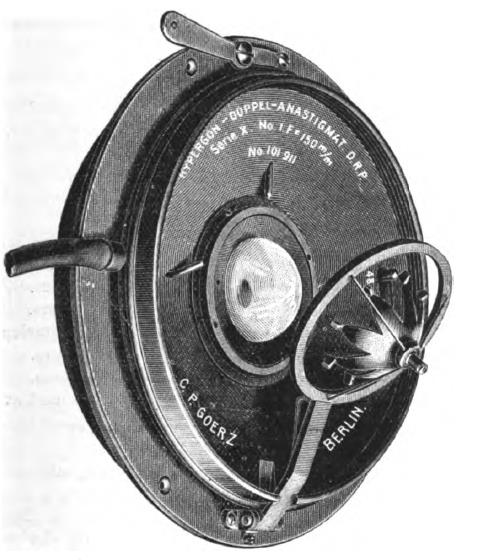

Telephoto lenses had existed for quite some time. There were also early wide-angle lens designs, such as the Goerz Hypergon; these generally involved pairs of meniscus lenses facing in opposite directions, possibly with other symmetrical pairs of elements, to form a lens that was spherical in shape. A cross-sectional diagram of the Goerz Hypergon, showing its two meniscus lenses, is shown at left; on the right is an image of the lens; this is the one infamous for the fact that during five-sixths of the time of an exposure, the metal star has to be put in front of the lens, caused to rotate by puffs of air from a rubber bulb (the left side of the image shows the tube from it coming in to the lens) to obtain balanced illumination of the photograph.

Later on, in 1932 (or 1933) the Metrogon, a diagram of which is shown at right, was developed by Robert Richter at Zeiss. This is an example of the simple form of a double-Gauss objective. Like the Hypergon, it had a problem with uneven illumination, but by this time it was possible to solve the problem much more neatly simply by putting a suitable gradient filter in front of the lens.

During World War II, the United States made extensive use of lenses of this design for aerial photography, particularly for mapping, as this lens had very low distortion.

But that didn't mean that it had no distortion at all, and so in the postwar period it was succeeded by a new design, the Planogon, which had still lower distortion.

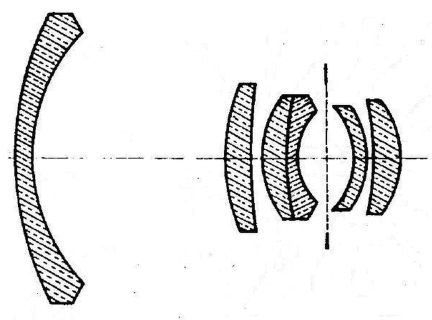

But modern wide-angle lenses, which use a retrofocus or inverted telephoto design are quite recent; they began in 1950 with the Angénieux Retrofocus R1 lens from France, shown at left, and the Flektogon by Carl Zeiss Jena in East Germany, shown at right, although the basic design had been used for special purposes as far back as 1930.

Both of these designs had numerous variations in practice; while the Angénieux design looks like a big concave lens in front of a Tessar, and the Flektogon design looks like a big concave lens in front of a Double Gauss lens, lenses under both names were also made with the portion in the rear part being of the other type.

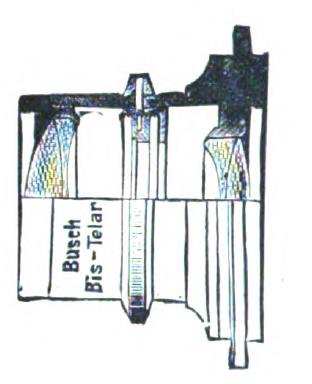

The earliest Zoom lenses were made for the motion-picture industry. In 1931, the mechanically-compensated Busch Vario-Glaukar was offered for use in 16mm cameras, and was one of the first modern zoom lenses available commercially. How it worked is shown at right.

As I remembered things, at first, Zoom lenses for 35mm SLRs changed over a range of telephoto focal lengths, but later Zoom lenses that crossed from wide-angle to normal to telephoto were developed, allowing photographers to avoid having to change lenses much of the time.

However, that wasn't quite right: the first Zoom lens offered for single-lens reflex cameras was the Voigtländer Zoomar in 1959; it had an aperture of f/2.8, and a range of focal lengths from 36mm to 82mm. A picture of it is shown at left, on a Voigtländer Bessamatic camera, from an advertisement for that camera. It was also made available in a variety of mounts for other cameras.

When I learned this, it was surprising to me. Zoom lenses that went from wide-angle to telephoto with ranges like 35mm to 135mm had been presented as a relatively recent phenomenon when I first encountered them; the most common and ordinary zoom lens was a zoom telephoto with a range of 80mm to 200mm, which nearly everyone seemed to make.

The Voigtländer Zoomar did have severe pincushion distortion at the extreme upper end of its range of focal lengths, but somehow I doubt that this is the reason it was not imitated for such a long time.

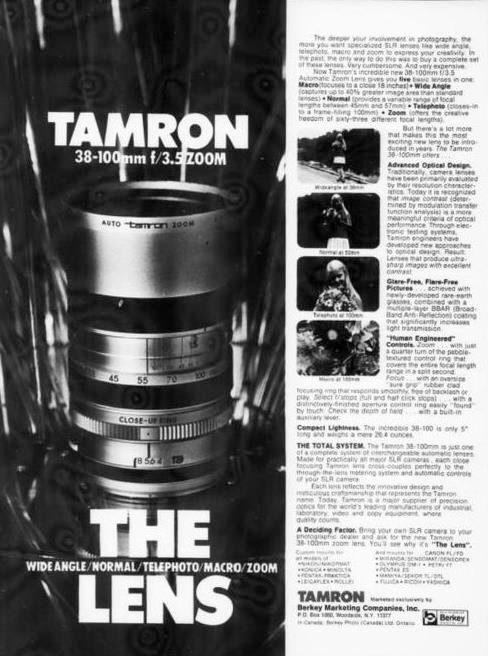

Having now checked, it seems that zoom lenses with a 35mm to 135mm zoom range started appearing in 1983, but similar lenses with a shorter zoom range of 35mm to 105mm had been around for some time before that. Kiron appears to have been one of the first makers of 35mm to 135mm zoom lenses, closely followed by Tamron.

I think I've finally found out who restarted interest in wide to tele Zoom lenses, after the 36mm to 82mm lens from Zoomar itself. Konica made a varifocal lens (this meant that, unlike the case with a "true" Zoom lens, changing the focal length of the lens would put images out of focus, and so the lens would have to be focused again) with a range from 35mm to 100mm starting in 1971.

Subsequently, though, I encountered another advertisement from Nikon in 1960 which mentioned that there were three Auto-Nikkor zoom lenses available for the Nikon F; one had a range of focal lengths of 35-85mm, another was the 85-200mm one mentioned, and a third had the range 200-600mm. So it isn't the case that the original Zoomar was the only wide to portrait zoom lens until the 1970s.

An advertisement for a 38mm to 100mm zoom lens by Tamron from 1974 appears at right as an early example of this genre of lens.

As for the ubiquity of the 80-200mm zoom lens, that trend seems to have been started by Nikon; shown at left is an advertisement by Nikon from 1960 for a zoom telephoto lens with a range of focal lengths from 85mm to 250mm.

For users of other brands of camera, Tamron had a 95mm to 205mm zoom available in 1964, and Sun Optical of Japan had an 85mm to 210mm zoom available in 1965.

In 1963, though, a zoom telephoto lens was also available, but one of a different kind: the Televar Zoom, the focal length of which ranged from 350mm to 650mm.

Oh, wait; even in 1963, you could get the Enna Zoom Lens, with 85mm to 250mm as its range of focal lengths, and the Astronar Zoom Lens with focal lengths from 95mm to 205mm. But it does not seem that third-party zoom lenses were widely advertised in 1962, so it did take a while before Nikon could be imitated.

Incidentally, the Enna Zoom Lens was made in West Germany, and is said to have been of excellent build quality. The version with the mount for Alpa cameras is apparently extremely rare, but that does not seem to be the case for other versions of this lens.

As for the optical design of zoom lenses, they require a considerable number of elements in order that aberrations will remain corrected as the lens is configured for different focal lengths. This requirement is increased when the lens is a true zoom lens instead of merely varifocal; while having to focus the lens again after changing the focal length is only a minor inconvenience in still photography, zoom lenses were originally developed for movie cameras, and thus a true zoom lens can zoom in on part of a scene as the audience watches. And a further increase is occasioned when the lens is optically compensated instead of mechanically compensated: in a mechanically compensated zoom lens, the mechanism for moving certain groups of elements within the lens as it zooms moves those groups at different rates so as to maintain focus and keep aberrations corrected.

Despite this, the optically compensated true zoom is the most common form of zoom lens in use.

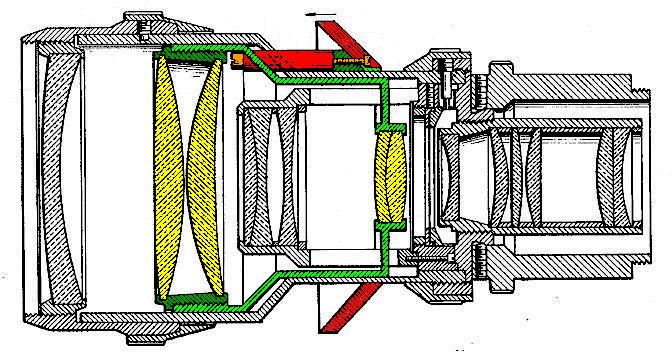

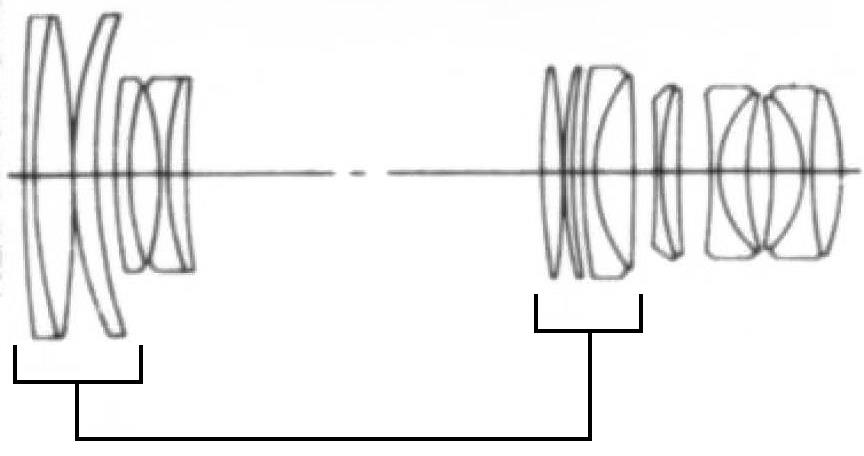

The following diagram shows the optical design of the original Zoomar lens for 35mm still cameras:

As their identity may not otherwise be clear from the diagram, the moving elements in this optically-compensated lens are highlighted in yellow, and the portions of the lens body that serve to move them are highlighted in red, (two shades of) green, and orange.

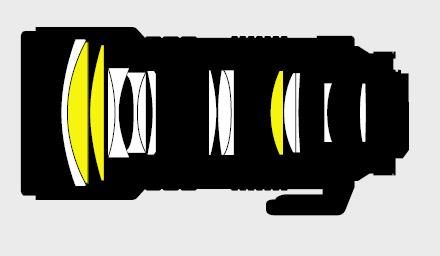

From an advertising brochure, here is an optical diagram for a modern Nikon zoom telephoto lens:

The lens elements highlighted in yellow are made from ED glass.

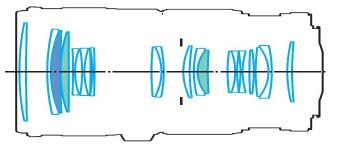

And, also from an advertising brochure, here is an optical diagram of a modern zoom telephoto lens from Canon:

In this diagram, the lens element in the front that is highlighted in darker blue is a fluorite element, and the two elements that are highlighted in lighter blue are made from UD glass.

At least to me, the designs of these two modern lenses appear very similar to that of the original Zoomar lens, even though that lens was not a telephoto zoom, but one which spanned the range from wide angle to portrait.

Zoom lenses do not have to be as complex as this, however. Thus, an inexpensive 95mm to 205mm zoom lens with a modest aperture can have a design as simple as that shown in this diagram:

Shortly after the Voigtlander Zoomar lens became available, a lens which was similar, but not an identical copy, was made in the Soviet Union, the Rubin-1:

The focal range of this lens was 37mm to 80mm, rather than 36mm to 82mm, so it was a slightly less ambitious design. While the original Zenit cameras used the M42 mount, a later line of Zenit cameras was made which used the DKL mount; there were three different model numbers depending on which lens came with the camera, and the Zenit-6 was the one that included the Rubin-1. Later, it was made available with other mounts, such as the M42 screw mount, for other cameras.

Much later, other zoom lenses were made in the Soviet Union, such as the Granit-11N and the Yantar 20.

As another example of the construction of a typical zoom lens, here is the optical diagram, from an advertisement, of an 80-200mm zoom lens from Soligor, to which I have added an indication of which of the lens elements in this design that I presume to be the moving ones.

It was in 1969 that Canon's 300mm f/5.6 FL-F lens became known as the first fluorite lens offered for photography, after Canon had perfected a process to grow large fluorite crystals. However, as far back as 1951, the 50mm f/1.8 Kern Switar was an apochromatic lens offered as the standard lens for the Alpa camera, so apparently apochromats for photography were possible before Canon's breakthrough. But another source claims that the f/3.4 Leitz APO-Telyt-R, from 1976, was the first apochromatic lens offered for general sale! This could only be the case if Canon's original fluorite lenses were not apochromatic, and it's hard for me to imagine any other reason to go to the trouble of using fluorite in a lens!

Looking into this further, I found it hard to find any use of the term "apochromatic" in connection with the early Canon fluorite lenses; however, the manual for the 300mm f/5.6 FL-F lens states "Canon FL-F lenses use elements made from artificially grown fluorite crystals as well as regular optical glass to completely eliminate color aberrations". Of course, completely eliminating chromatic aberration is an exaggeration, but apochromats do have chromatic aberration that is at least an order of magnitude lower than ordinary achromatic lenses, and so this does appear to clearly describe a lens that is designed to be an apochromat.

Also, other apochromatic lenses were available for the Alpa, manufactured by the French firm of Kinoptik, well before 1969.

Before Canon's breakthrough, defect-free pieces from natural fluorite crystals were used to make the small lenses needed for the manufacture of apochromatic microscope objectives.

Why is fluorite so important for making apochromatic lenses?

Isaac Newton studied how glass prisms break light up into different colors. He noticed that flint glass dispersed light into these colors more strongly than crown glass, and it also had a higher index of refraction than crown glass. But as he didn't measure these two phenomena quantitatively, he came to the assumption that this meant there was no way to use these two glasses together to cancel out the dispersion of colors.

So he went on to invent the Newtonian reflecting telescope, which avoided the problem of chromatic aberration entirely, except for the eyepiece.

In fact, as we now know, the degree to which flint glass disperses colors more strongly than crown glass is greater than the degree to which flint glass has a higher refractive index than crown glass.

So it is possible to make a lens consisting of a strong convex lens made of crown glass, and a weaker concave lens made of flint glass, which acts like a weak convex lens with almost no dispersion of colors. This is an example of an achromatic lens. Of course, one can also make negative achromats as well.

It was in 1758 that John Dollond read a paper to the Royal Society which established the fact that achromatic lenses were possible. He began his researches into such lenses, however, after being told about such lenses having previously been made according to a design by Chester Moor Hall in 1733 or thereabouts. Further improvements in the achromatic lens were carried out by Fraunhofer.

In designing such a lens, usually the goal is to bring red and blue light to the same focus. If that is done, yellow light will not be brought to that focus; there will still be some residual chromatic aberration, but it will be much less than that of a plain lens with only one kind of glass.

An apochromatic lens is one where a third transparent material is used so that three wavelengths of light are brought to the same focus. The ones in between will still not be focused at exactly the same distance, but the difference will now be considerably less than that for the in-between wavelengths in a mere achromat.

But while Newton was wrong about it being impossible to make an achromatic lens from different kinds of glass, when it comes to apochromats, Newton was right - all ordinary glasses are similar in such a way that trying to make an apochromat from three of them just doesn't work.

So making an apochromatic lens requires that one use a transparent substance that's different from glass. Some early attempts to do this used water or mineral oil, but two of the earliest used more exotic fluids: Robert Blair used hydrochloric acid in which metal was dissolved, and Peter Barlow used carbon bisulphide.

The Magic-8 Ball included an ingenious scheme to ensure that the inevitable bubbles in a liquid-filled container would be confined to a subsidiary compartment, leaving no bubbles in the main one; this scheme could be used to make liquid-filled lenses practical if someone wished.

Apochromatic telescope lenses that did not require a liquid element did exist as far back as 1899; the lens of which I speak is the Cooke photovisual objective. This lens was described in a paper published in 1894, and patented in 1892. So why weren't apochromatic lenses for cameras continuously available from that point on?

One source states that this was because the Cooke photovisual was based on a new glass available from Schott, but a few years later it was learned that this glass deteriorated after only a few years, thus making the Cooke photovisual objective a false start, as any substantially similar glass using the same substances in its formulation to achieve the same optical properties would have the same problem; it wasn't correctable by a small change that would leave the desired optical properties intact.

I have found further information on this point. The problematic glass from Schott was a boro-silicate flint, and Cooke was able to address the issue by sealing off the element from the air, so that the traces of sulphur compounds in the glass would not oxidize and cause the deterioration.

This presumably is why there are surviving Cooke photovisual objectives that are still usable. There was another possible reason why the design could not be extended to apochromatic camera lenses: while the Cooke photovisual objective met the technical definition of an apochromat, the wavelengths of light it brought to the same focus weren't red, yellow-green, and blue; they were red, blue, and ultra-violet, in order to accomodate the needs of photographic emulsions which were sensitive to ultra-violet light.

This wider spacing of the three wavelengths involved, with only two of them being within the visible spectrum, presumably meant that the improvement in color correction for visible light compared to an achromat would have been limited; yet, the lens was described as completely eliminating chromatic aberration, and so apparently the advantages of an apochromat, while possibly slightly reduced, weren't lost by extending the range of wavelengths to correct in this way.

Acrylic plastic is sometimes used for lenses, and it also differs from glass in the way that's needed to make an apochromatic lens. But the substance now generally used to make apochromatic lenses is the mineral fluorite (CaF2); it is a solid, unlike water or mineral oil, and, in addition, it does not have the drawback of having a refractive index that changes rapidly with temperature, unlike transparent plastics. But fluorite does have the drawback that it dissolves in water, and so fluorite glasses, where fluorite is mixed with glass, have been developed to reduce the impact of this issue.

There aren't many choices for a transparent material that has the properties that make it a good material to make lenses out of, like glass, but which also isn't glass, thus having different optical properties - specifically, what is called anomalous partial dispersion. That's because of one other problem which hasn't been mentioned. What about sapphire, a transparent material made synthetically and used for some watch crystals? Unfortunately, like calcite (CaCO3), sapphire is birefringent. A lens made from it would produce double images, because it refracts light differently based on the direction in which it is polarized.

As I have also read that fluorite glasses were devised in reaction to Canon's patents (I have now found that there were fluoride glasses invented much earlier, though, specifically those described in U. S. Patent 2,511,224, so they are another possibility), so that other lensmakers could compete, at first this made me suspect that Switar and Kinoptik did use larger defect-free pieces of natural fluorite; as they were merely advertised as apochromats, the term "fluorite lens" would still only gain currency when Canon got started.

A brochure of theirs I've found online only mentions that they used Lanthanum rare-earth glass. I knew that Lanthanum was used to make lens elements with high refractive index and low dispersion, but I wasn't aware that it had anything to do with making apochromatic lenses.

However, while most conventional optical glasses indeed can't be used in making apochromatic lenses, some of the metal oxides added to glass do cause it to have anomalous partial dispersion, and Lanthanum oxide is one of them.

The high-performance optical glass used in many lenses dates back to U. S. Patent 2,466,392 from Eastman Kodak. This glass contained "lanthanum oxide and thorium oxide in substantially equal amounts", and so it was radioactive. This patent was applied for in 1945; however, an earlier patent, applied for in 1936, U. S. Patent 2,150,694 included glass formulations both with and without Thorium. Eventually, it was discovered how to do without the Thorium oxide for the type of high-performance glasses desired; during World War II, Kodak did manage to make a similarly high-performance optical glass with no Thorium oxide, but it had a yellow tint. Lenses made from it could still be used in aerial photography cameras which took their pictures on black-and-white film.

Later on, it was learned how to make Lanthanum glass without the yellow color. There was precedent for this; it's very common to include a little Manganese oxide in glass in order to counteract the green tint that Iron, often an unavoidable contaminant in sand, causes in glass.

U.S. Patents 2,861,000 and 3,009,819, both of Schott, seem to describe the invention of the first modern forms of Lanthanum glass, rather than the one applied for in 1936 noted above, given that despite the earlier patent, such glasses without Thorium did not exist except for a version with a yellow tint. And thus this kind of glass was available at least from around 1953 onwards.

So I was able to find, in my researches, enough information online to settle the matter. Glasses using Lanthanum have anomalous partial dispersion, so they are a way to make apochromatic lenses without resorting to fluoride. But then why use Fluorite, or even Fluorite glass, at all, since it is fragile in a number of ways? One site I encountered, but can't find again, noted that the residual chromatic aberration of a Lanthanum-based apochromat is several times greater than that of a Fluorite-based apochromat.

This surprises me. What I would expect is, if one material is poorer than another for making an apochromatic lens, is that the consequence of using the poorer material would be that an apochromatic triplet made with it would have to be thicker - chromatic aberration would be cancelled to about the same extent in the end, but there would be more spherical aberration to deal with, because each element would have to refract the light more strongly so that the same amount of refractive power is left over once the dispersions cancel each other out.

Just as Lanthanum substitutes for Thorium now because of the radiactivity of the latter, today many types of flint glass are made with Titanium oxide which replaces lead oxide, now not used because of the toxicity of lead.

One fact of which I was aware is that some astronomical refracting telescopes, despite having objective lenses with only two elements, are advertised as being apochromats, since they use ED glass, which I knew to reduce chromatic aberration below that of ordinary achromats; as I noted above, I was initially unaware that low-dispersion glasses such as Lanthanum glass did also have anomalous partial dispersion.

The definition of an apochromatic lens is one where there are at least three elements, with three different kinds of glass (or other refracting material) used, with the distribution of refracting power between the elements of each type of glass being such that light at three different wavelengths is brought into focus at the same distance from the lens.

It would seem that two-element lens, no matter how fancy the glass might be in one of those elements, cannot meet that definition. However, I have now recently learned that it is possible to choose two glasses with matching optical characteristics from which a genuine apochromat can be made with only two elements.

I have also recently learned that Lanthanum is also radioactive, but very slightly, because one of its naturally-occuring isotopes, Lanthanum-138, has a half-life of 1.02 * 10^11 years, and an abundance of 0.09%, which only results in a very slight degree of radioactivity, so that it continues to be used in lenses.

In my search for more information about the apochromatic camera lenses which preceded 1971, I encountered a web site about Eastern European camera lenses with a great deal of information. On one page, I saw the claim that a lens was radioactive because it contained Tritium. I found this odd, and felt that this must be a typographical error for Thorium and so I contacted the site. I recieved a response giving their source for this information.

This led me to becoming aware of a statement in the German-language version of the patent for an Olympus six-element 50mm f/1.4 lens, apparently the same one as described in U.S. Patent 3,984,155, that one particular hard flint containing Lanthanum, LaSFO5, did pose a radiation hazard due to there being Tritium present in that type of glass. This was given as the motivation for the invention, that type of glass having been used in the front element of the lens that was the predecessor of this lens.

I was baffled by this when I first heard of it, as I could not imagine any reason why Tritium would be used as an ingredient in any type of optical glass. I have seen statements online saying that some Lanthanum glasses are radioactive to a dangerous extent because they also contain some Thorium. (This, of course, raises the possibility that Tritium was a typo for Thorium in the patent itself, if not on the web site.)

In thinking about the matter, I came to the conclusion that what was likely going on (assuming no typographical error was involved) was that the hazard resulted from Tritium accumulating in the glass due to the decay of the Lanthanum (or, for that matter, from a Thorium contaminant, if present). I can only guess that this would be because there are substances in the glass which react with hydrogen, causing the Tritium to be retained instead of leaking out of the glass harmlessly as would be more usual.

I've also just now learned that Pentax once made Ultra-Achromatic lenses; this was their term for lenses that were corrected so as to bring four different colors of light to the same focus, not two as in an achromat or three as in an apochromat. The lens was an f/4.5 80mm lens, and it is believed that there are only 40 of them still in existence! My first reaction is to ask: have their patents expired yet, and why has no one else yet tried? But given that apochromatic lenses already provide better color correction than anyone really notices, perhaps I should not be too surprised that something that would greatly increase the cost (and size and weight!) of a camera lens for which there is no real need is not being done.

Telescopes that are called "Super Apochromats" or similar names do exist; but these are corrected for three wavelengths of visible light and one wavelength of infrared light to allow astrophotography beyond the visible spectrum, not for four wavelengths of visible light.

Another exotic technology that largely only started being used in camera lenses relatively recently is the use of aspheric lenses. For example, Canon's first single-lens reflex camera lens with an apheric element dates from 1971, and Nikon made a 10mm fisheye lens with an aspheric element starting from 1968.

The Kodak disc camera used a lens with an aspheric element, and the Precision Glass Molding process used to make it was invented at Kodak. However, elsewhere I have seen Hoya credited with developing a precision molding process for optical glasses in the early 1980s; possibly this was a significant improvement on Kodak's older process. Molding aspheric lenses from plastic is simpler, and I vaguely remember seeing an advertisement which noted this was being done for one popular model of camera; however, I have not been able to locate the details at this time.

The mirror in a Newtonian telescope is usually a paraboloid, and the corrector plate in a Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope is also, of course, aspheric, so the technique is not entirely new. It was in 1668 that Francis Smethwick presented a telescope with three aspheric lens elements to the Royal Society.

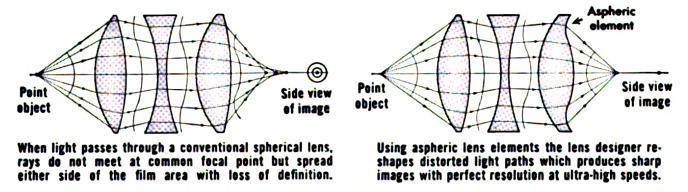

This diagram, illustrating the advantages of having an aspheric component in a camera lens,

is from a 1956 advertisement for the Golden Navitar lens for movie cameras from Elgeet. This was the first commercially mass-produced aspheric lens, and it was manufactured using a membrane polishing technique.

Extreme aspheric lenses are also commonly used today to make the very thin cameras found in smartphones possible.