In a previous section, I noted how electronic programmable scientific calculators started out as devices for the desktop, and then became pocket calculators.

I had briefly mentioned the Osborne I, the Kaypro, and the original Compaq, which were portable, although portable computers of the type called "luggables". But as we all know, computers didn't stop becoming available in smaller sizes there: the laptop computer came along, and even the pocket computer - and while the pocket computer was not a long-lived product category, the personal organizer was seen as a bit more practical, and of course, these days we're all carrying full-fledged computers in our pockets; but as we can also make telephone calls with them, we call them smartphones.

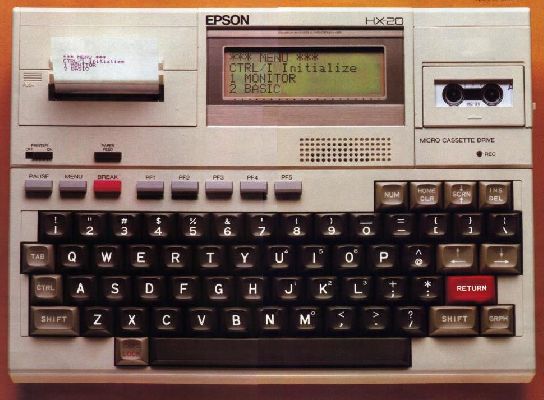

On the right is an image of the EPSON HX-20 portable computer. Note that it has a (thermal) printer, a display, and a micro-cassette drive for external storage, to make it not merely the first easily portable computer, but also the most complete one in that class. Originally released in Japan in 1981, it reached the North American market in 1982.

(Incidentally, the image is from an advertisement that originally occupied two pages in the magazine in which it appeared; it has been extensively retouched to replace the portion lost in the gutter between those pages, and so I apologize for any unintended inaccuracies. I felt it was worth the trouble, given its historical importance as the machine that started it all.)

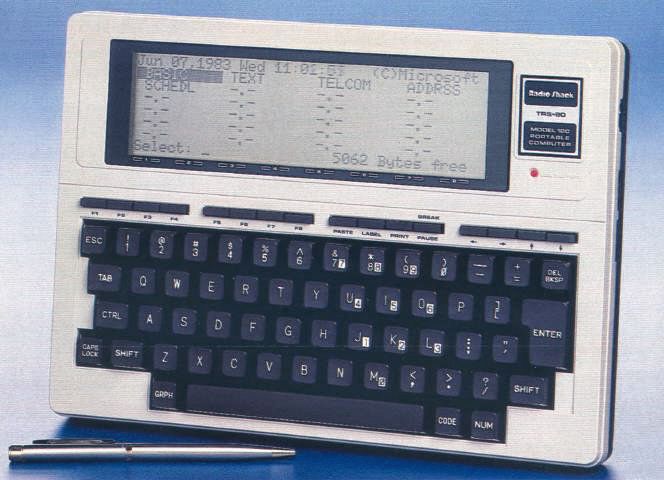

A similar computer made by Kyocera came out shortly after, and a heavily modified version was offered to the Western market. This one eschewed both the printer and the cassette drive in favor of a larger display, and it had a keyboard with what I view as the ideal arrangement for a computer keyboard: typewriter-pairing rather than bit-pairing, and with both shift keys, the back space key, and most especially and uniquely, the Enter key, all in the positions where they would be found on an electric typewriter, for the greatest convenience in touch-typing.

It is the TRS-80 Model 100 of which I speak, pictured at left.

Later, in 1985, a successor to the Model 100 came out, the Model 200, pictured at right. This had much the same keyboard layout, although with the cursor pad improved, and a 16-line display that folded up in typical laptop fashion. However, by that time, more alternatives were available, and so it did not make nearly as much of a splash as the Model 100 did.

From 1985, a computer that did not become very popular, but which is fondly remembered for its impressive styling, its 68000 processor, and its use of the language APL, the Ampere WS-1, shown to the right, is worth mentioning.

Placing the trackball above the screen does not seem like a wise decision, but perhaps this computer was not designed around a graphical user interface, and so the trackball would only be used on a very occasional basis. Even making an infrequent task awkward and painful, however, does not recommend itself.

Note the presence of a microcassete drive below and on the right of the keyboard. This, instead of a floppy disk drive, on a system which, due to the use of a powerful 68000 processor, would have been expensive at the time, may have been one reason for its lack of popularity.

In my opinion, however, a digital cassette tape drive (rather than an audio cassette drive which would store digital data with much lower density, and possibly lower reliability) would be a perfectly reasonable alternative to a floppy disk for external storage... on a system which also had a hard disk, so that random access to stored data would not be lost as a capability of the system. But since in those days, a hard disk was expensive enough to always be an optional extra, one had to start with just a floppy drive, and so changing to something else after adding a hard drive would be incompatible.

And indeed, the Ampere WS-1 did not have a built-in hard drive. One could get both a hard disk and a floppy disk that plugged into it as external peripherals, however.

So, while the combination of a hard drive with a cassette might make sense in itself for a particular machine, it did not happen because it did not make sense in the context of a line of machines some of which would not have a hard disk.

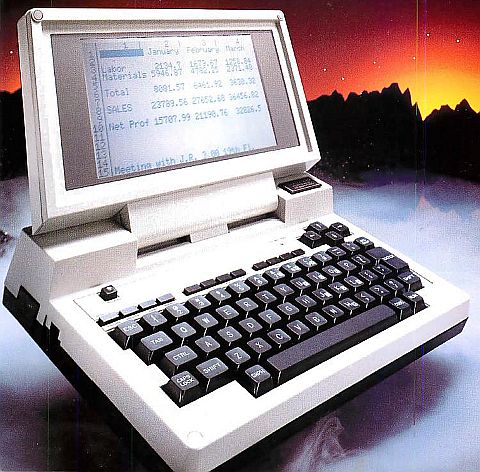

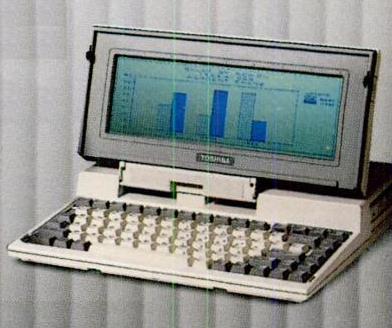

At first, when I started work on this section, it didn't seem that I could feature any typical or ordinary laptop here. However, while the Toshiba T1000 was not the first laptop computer to be compatible with the IBM Personal Computer, when it was introduced in 1987, it was both so light in weight and reasonable in price compared to what was previously available as to make a laptop computer a reasonable option for many more computer users than had previously been the case.

Also, while it was quite compact and light for its day, it is still significantly different in appearance from the laptops of today, as while the display unfolds from the keyboard, the display and keyboard together occupy a space at the front of the laptop rather than the whole of its depth as is the case with most laptops today.

This conventional form factor for laptops originated in early 1982, with the GRiD Compass. This laptop was not compatible with the IBM PC, although it did use an 8086 microprocessor, along with an 8087. Its body was made from magnesium, and its display was amber in color and electroluminescent in nature. It weighed 9 1/4 pounds, and cost $8,150.

One place it was used was aboard the Space Shuttle. The units used there were modified: the modem it included was removed, and replaced by a small fan: normally, convection was sufficient to cool it, but under microgravity conditions, hot air has no "up" to which to rise, and so the motion of air must be forced.

The image at right is from a publicity shot released when the computer was first announced. Below are two NASA photographs, the first of the normal computer on the ground, and the second a detail from an image of the modified version for use on the Shuttle, designated SPOC (for Shuttle Portable Onboard Computer) held by astronaut John O. Creighton.

Of course, it's not difficult to guess what inspired the acronym for the Space Shuttle version of this computer. Here is a photograph of the actress Nichelle Nichols from 1977 at Mission Control, a still from a promotional film in which she participated aimed at encouraging the recruitment of minority astronauts made in that year:

which was part of efforts associated with NASA contract NASW-3049, through which Nichelle Nichols' Women in Motion Production Company was hired from February 10, 1977 through August 10, 1977 both to review NASA recruitment activities and to inform and encourage minority participation in NASA opportunities.

And here is an image showing, from left to right, NASA Administrator James Fletcher, DeForest Kelley, George Takei - and, standing behind him, James Doohan - Nichelle Nichols, Leonard Nimoy, Gene Roddenberry, NASA Deputy Administrator George Low, and Walter Koenig, from the rollout ceremony for the Space Shuttle that was christened Enterprise (it was used as a test vehicle, flying within the Earth's atmosphere for tests, but never in space).

and, of course, few will fail to recognize the fact that it was Leonard Nimoy's character that was reflected in the acronym for the version of the GRiD Compass used aboard the Space Shuttle.

Most people reading this page know what a laptop computer looks like, and if they have forgotten what a smartphone looks like, they can reach into their pockets!

So, why don't I instead include an image of something which at least some of the readers of this page may not have seen, or if they have seen it, or pictures of it in magazines, they at least may no longer remember it?

Something which, at least for its time, was incredibly unique and unexpectedly powerful for its size?

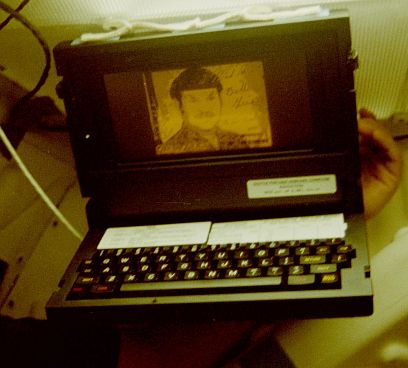

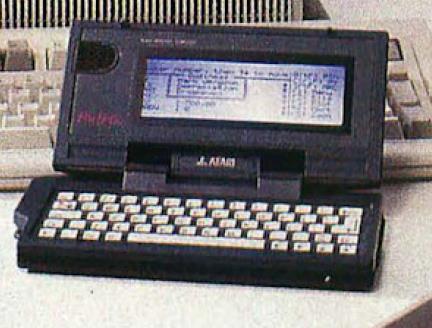

And so, from October, 1989, I bring you an image, on the right, of the incredible Atari Portfolio!

Unfortunately, it was not all that successful, as far as I recall. Although this handheld device was compatible with an IBM PC running MS-DOS, the fact that it had a text-only display with only eight lines of text meant that a lot of software for the IBM PC would not run on it, and that left many potential purchasers unsure as to what they could actually use it for - or, perhaps more precisely, what the value of presumably paying extra for IBM PC compatibility would be under such circumstances.

On further reflection, I think what happened was an error in marketing. The unit was made MS-DOS compatible so that people would be reassured they could transfer information, using an attached floppy drive, from their PC to this device in order to use it anywhere they could carry the small device. But by claiming it was compatible, even though clearly there would be much PC software that couldn't run on it, potential customers focused on the claim of compatibility, seeing it as a gimmick, since compatibility was generally defined as the ability to run any and all software for a the system one is claiming to be compatible with.

So people did not see the device on its own terms, and understand what the level of compatibility it offered was for; the means used to reassure people about its ability to use data from PCs led to confusion that hindered interest.

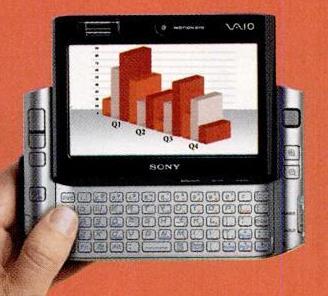

But come to think of it, when it comes to small computers, I can think of one other one that is special. The Sony Vaio UX is famous for being a PC-compatible computer able to run Windows XP that can be worn on one's wrist!

At the time, this was simply amazing and unbelievable. But while it was an impressive feat, it was also expensive, and not many people in the North American market, at least, felt they had any reason to pay a price premium for a level of portability that interfered with usability.

In other markets, however, portability is more highly valued, and thus a lot of interesting mini-laptops are available in Asian countries that never make it to North America.

Thus, the Eee PC from ASUS, a small and thin laptop, was noticed when it was available in North America. The first model came with Linux, but the second model, the Eee 900, which came to North America in late 2008, ran Windows.

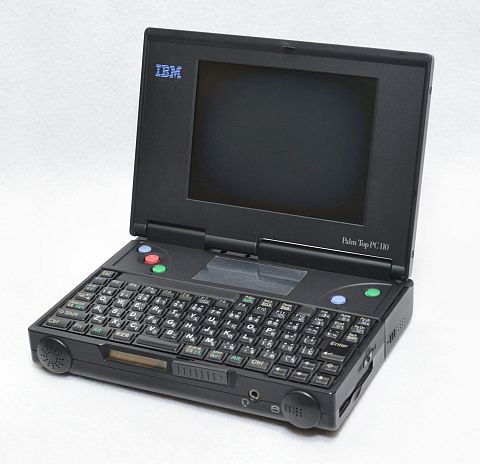

As far back as 1995, IBM made the PalmTop PC110, which was only available in Japan.

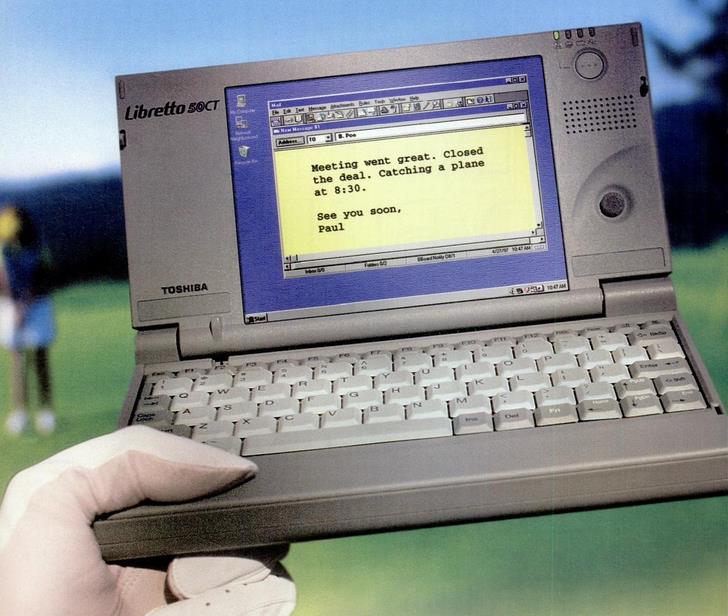

One example of a laptop in the UMPC form factor that was briefly available in North America was the Toshiba Libretto. The first one available in this market was the Toshiba Libretto 50CT, pictured at right.

The computer was 21 centimetres in width, or just slightly over 8 1/4 inches. The standard 3/4" width of a typewriter key is 19.05 centimetres, and while it appears the unit would have had to have been a bit wider to accomodate that, the difference is sufficiently slight that no doubt it actually was possible to type normally on its keyboard.

But what if someone came up with a laptop that, although it was not as wide as a keyboard with full-sized keys, still offered such a keyboard, by the expedient of having a mechanical linkage which caused the keyboard's left and right halves to move to a side-by-side position from an overlapping position when the laptop was opened?

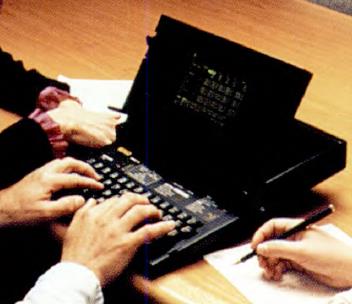

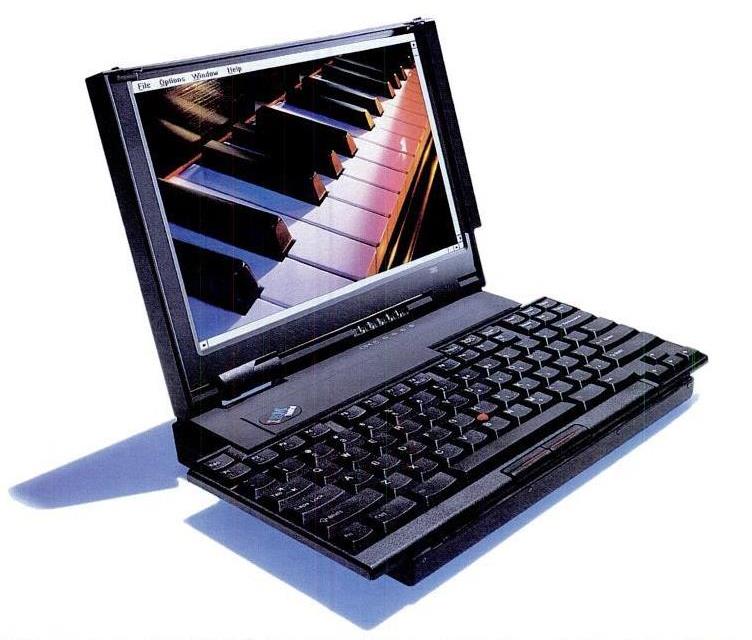

Of course, IBM did come up with just such a laptop in 1995, the famous ThinkPad 701c with its "Butterfly" keyboard, pictured at left. However, it was somewhat expensive, and, as well, the market shifted its interest to laptops with more powerful processors, specifically the Pentium, and larger screens.

|

The image above is from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 4.0 International License, and is thus available for your use under the same terms. Its author is Ariga. |

Well, at least in North America, and possibly Europe. In September 1995, only in Japan, and with some help from Ricoh (famous maker of 35mm cameras, photocopiers, and, at one time, slide rules) IBM came out with the Palm Top PC 110, the keyboard of which was definitely too small for normal typing, as the laptop as a whole is merely 158mm wide, or about 6.22 inches or 6 7/32 inches, as you may prefer.

Fitting fifteen keys across into six inches of space means that each key was just 0.4 inches wide, instead of the usual 3/4 of an inch, or 0.75 inches, so the keys were only slightly more than half the width of normal keys.

As the price of the unit was comparable to that of a normal laptop, but so small a keyboard badly compromised its utility, naturally the device would be percieved more as a toy than a genuinely useful laptop well worth the full price of a laptop computer, at least by some people, despite the fact that it had a 486 SX processor, and thus performed reasonably well. This perception, of course, is common to very compact computers in general, and is not unique to this particular IBM product. As this perception is stronger in North America in particular, and the West in general, than in some other places, this is why many UMPCs are only available (or, at least, only formally distributed) in Japan, South Korea, and other nations of the Far East.

Note that I have modified the image at right in order to enhance its contrast, so it may not look exactly like the original image to which I have given credit.

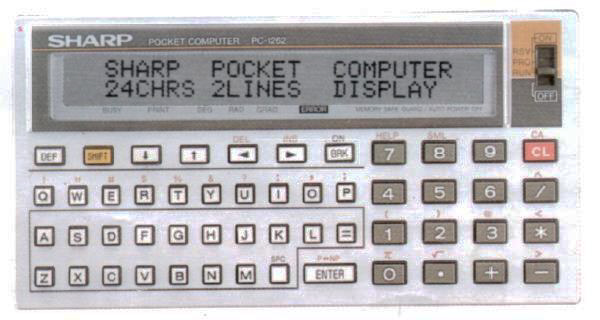

Just as the first laptop computers had 8-bit microprocessors, instead of being compatible with the IBM PC, the same was true with form factors smaller than the laptop.

Thus, for a time in the 1980s, a number of companies made pocket computers, which could be programmed in BASIC, with an LCD display of from one to four lines, such as the example from SHARP pictured below:

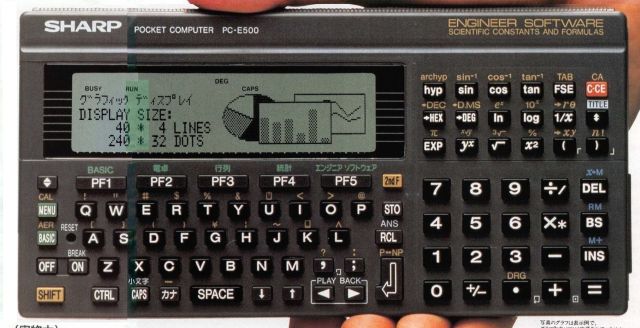

Some pocket computers also included keys similar to those found on a scientific calculator; an example of this is the SHARP PC-E500, pictured below:

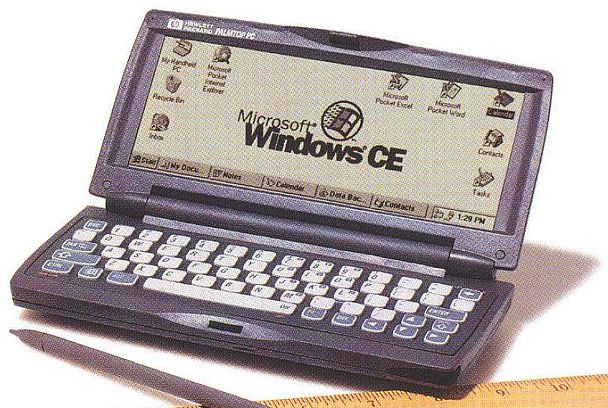

And then, later on, Microsoft made an operating system that resembled Windows, but which ran on the MIPS microprocessor, for use in handheld devices such as this one from Hewlett-Packard:

The first release of Windows CE took place on November 16, 1996; later, the operating system was renamed to Windows Embedded, and emphasis was placed on other categories of application.

Windows 8 added new features to Microsoft Windows which made it possible to use the Windows operating system on a tablet computer, with only a touchscreen and no keyboard. (Of course, to allow existing software to be used, one of those features was an onscreen keyboard.)

In addition to tablets that ran Windows 8, a number of manufacturers offered laptops which could also convert to tablets; this was most commonly done by having a special hinge on the laptop, so that the screen could be opened further, so that it rested against the bottom of the keyboard portion. Also, tablets were made that had thin portable keyboards to dock with available.

An alternate solution was the Dell Inspiron Duo laptop from 2010, as illustrated below. On this computer, the display portion of the laptop contained a display that could be rotated on a horizontal axis within an outer frame; then the laptop could be closed normally, and the display would be on the outside.

This had the advantage that the keyboard was not on the outside on the back of the unit when it was being used as a tablet.

The Inspiron Duo was criticized for being heavy and underpowered with its Atom processor; in 2012, Dell used this ingenious design again, with the XPS 12, pictured at right. This laptop was thin and light, with a powerful processor, and a premium price to match, for which it was criticized instead.

I suppose one could draw the conclusion from this that one just can't satisfy some people, but Dell did have the option to offer this very useful feature in a midrange machine instead of only first at the bottom end, and then later at the top end, of its range.

A similar form factor, except with the display on a support which extended only to the pivot points, rather than all the way around it as a frame, was used in the Vadem Clio from 1998. This device ran Windows CE, and it was also sold as the SHARP Mobilon TriPad, pictured at left.

The image illustrates how this configuration offers some additional flexibility; the display can now also be moved forwards, since it doesn't need to be placed completely within the frame for use as the top part is no longer there to be an obstruction.

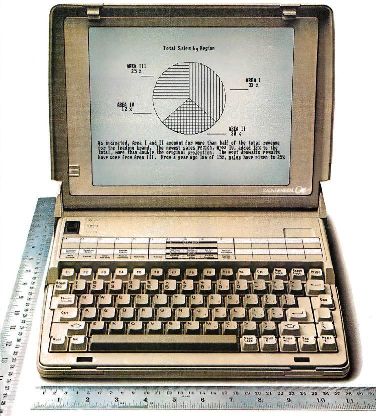

In addition to the Toshiba T1000, there is one other laptop computer with a conventional form factor that is so historic that I feel it is worth mentioning and picturing here. Shown at right is the Data General One laptop computer. The portion with the keyboard does extend somewhat behind the screen, so the unit doesn't have the modern "clamshell" form factor, but it was still remarkably thin and light for its time.

The Data General One was a technological feat when it came out in 1984, and thus was somewhat expensive (initial price $2,895 U.S.) compared to the ordinary and less compact portable computers of its day. The technology wasn't quite ready for it; its liquid crystal display had to be made from four individual panels carefully joined together.

Data General, of course, is much better known as a minicomputer company, coming out with the Nova minicomputer after Edson de Castro left DEC over a disagreement about the direction the company would take in developing a new 16-bit computer. Eventually, of course, DEC developed the PDP-11, which was extremely successful and influential, and very different, architecturally, from such 16-bit computers as the Honeywell 316 or the Hewlett-Packard 2115, which were both very similar to such existing DEC minicomputers as the PDP-9.

The architecture of the Nova was a more modern one than that of those other computers, but it was very different from that of the PDP-11. The Nova was followed by an upwards-compatible and higher-performance computer, the Eclipse.

Another claim to fame for Data General has to do with a later machine in the Eclipse line. The Eclipse MV/8000, introduced in 1980, and pictured at left, was Data General's answer to the VAX from the Digital Equipment Corporation.

Digital Equipment Corporation's first machine in that series (that is, its first VAX), the VAX-11/780, announced on October 25, 1977, included the ability to execute programs for the PDP-11 when running in 16-bit mode. When running normally, in 32-bit mode, however, its instruction set was completely different.

Advertising for the Eclipse MV/8000 emphasized a feature of that computer: the new instructions which performed 32-bit addressing or 32-bit calculations were additions to the existing Eclipse instruction set; the computer did not work by switching modes. Presumably, the prospective customer was intended to feel that this higher degree of compatibility with the very popular older architecture this offered made the Data General MV/8000 a superior choice compared to the VAX-11/780 from the Digital Equipment Corporation.

I have to admit that I never saw the logic of this. A slight gain in the efficiency of running 16-bit programs, made to run on a less powerful computer, and hence less capable, at the cost of a large loss in the efficiency of running the more powerful 32-bit programs that the computer would mostly be used with in the future (otherwise, why pay extra for a bigger computer) seems a bad bargain. In the specific case of the Data General Nova architecture, it was even worse, because the instruction set used up nearly all of the possible combinations of bits in a 16-bit word, leaving little to spare for 32-bit extensions!

No wonder Edson de Castro was offered by one of his engineers a scheme, which, of course, he rejected, with the comment "we're not going to do this", which was essentially a sneaky way to do what a mode bit would have done without actually having a mode bit! Of course their integrity as engineers drove them to rebel against such huge inefficiencies in the name of marketing!

This unique feature made it possible, when the book by Tracy Kidder, The Soul of a New Machine, which chronicled the development of an unidentified new computer at an unidentified computer company... which happened to have this particular feature... was published, to realize exactly which computer's development she was chronicling.

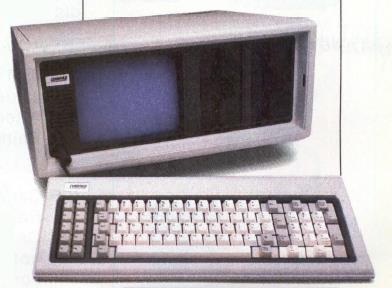

Portability in computers, of course, didn't begin with the laptop. Before laptop computers were possible, we had such computers as the Kaypro II and the Compaq Portable (shown at right), which whe already saw on previous pages.

As noted, the Compaq Portable was announced on November 1982, and became available on March, 1983.

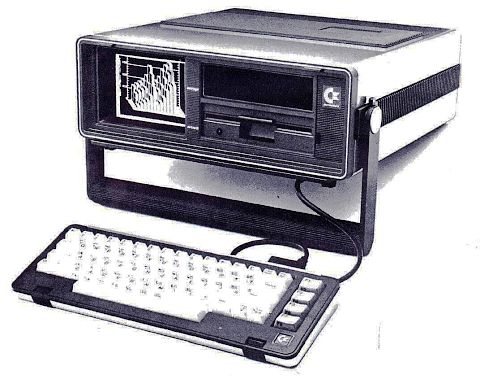

In 1983, Commodore announced the SX-64, which became available in 1984, shown at left. This computer had a color screen. The small size of the screen was less of an issue, given that the Commodore 64, of which this computer was a portable version, displayed 40-column lines of text, not 80-column lines like the Compaq Portable.

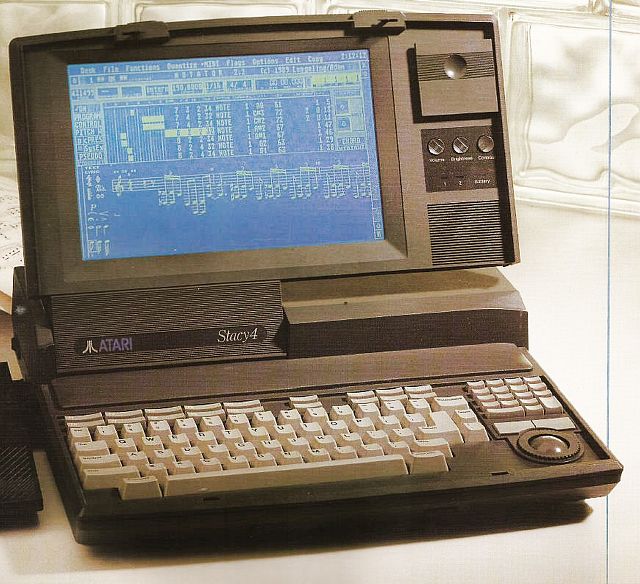

The Atari STacy dates from September, 1989. It had a liquid crystal flat screen display, but it needed to be plugged in to operate. It was originally planned to have it also run on twelve standard C-cell batteries, but it was realized that the computer's power consumption was such that it would not have been possible for a reasonable battery life to be provided.

This computer is quite stylish in appearance. It is bulkier than a modern laptop computer, but that lets it provide a full-sized keyboard with full-height keys having full travel. Note the keys of the numeric keypad are reduced in size, and the computer has a built in trackball rather than a trackpad.

Neither the Commodore SX-64 nor the Atari STacy was particularly successful in terms of the number of units sold. To me, this is hardly surprising. People bought a Commodore 64 instead of an Apple II or an IBM PC, and they bought an Atari ST instead of a Macintosh, because those computers were far less expensive. So those who chose to go with these computers, and the software available for them, weren't those who would have been willing or able to pay the extra cost required for portability.