On the first page of this section, one of the keyboard layouts I showed was a typical layout for a three-bank manual typewriter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

Q W E R T Y U I O P

@ $ % ! _ * / - #

A S D F G H J K L

( ) ? ' " : ; &

Z X C V B N M , .

This is the keyboard arrangement found on a Corona typewriter. Other typewriters used different arrangements of characters.

For example, some later Blickensderfer typewriters used this arrangement of characters:

" # $ % _ & ' ( 0 )

Q W E R T Y U I O P

/ - ¢ ; : ! ^ 1

A S D F G H J K L .

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Z X C V B N M ?

,

The Blickensderfer was a manual typewriter that had an interchangeable typewheel, thus providing the flexibility of changing between different styles of type on a single machine long before the IBM Selectric typewriter was invented. But unlike the Selectric, I suspect that the mechanism of this typewriter hampered the speed of typing compared to that on conventional manual typewriters.

Be that as it may, another thing that likely greatly hampered the popularity of the Blickensderfer typewriter was that most of them had a keyboard layout like this:

" ( ) _ ; * ' :

Z X K G B V Q J

% / - ¼ ! ½ + ¾ = £

& P W F U L C M Y ?

. ,

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

D H I A T E N S O R

It would appear to me that it was intended that on this type of keyboard, the bottom row of keys, rather than the middle row, was to serve as the home row. This makes sense on a three-bank keyboard, since even the double up-reach to where the number keys are on a four-bank keyboard is easier than a down-reach.

Presumably, this arrangement of keys could be adapted to the conventional layout of a four-bank keyboard to produce something like this:

! " # $ % _ & ' ( ) * +

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - =

@ ? ¼

¢ P W F U L C M Y / ½

:

D H I A T E N S O R ;

Z X K G B V Q J , .

Since the conventional layout of keys on a typewriter was modified to prevent typewriters from causing the typebars on a mechanical typewriter to jam from typing too fast, now that the keyboard is connected to an electronic device, the computer, it is not surprising that some have suggested that a more efficient keyboard be used with keyboards today.

In fact, since mechanical typewriters improved during their reign from the earliest model, this possibility was considered long ago.

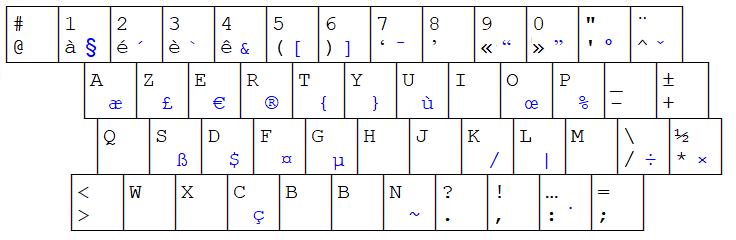

Slightly different keyboard layouts are used in some countries speaking languages other than English which still use the Roman alphabet.

Thus, in France and Belgium, the normal keyboard layout arranges the letters in this manner:

AZERTYUIOP QSDFGHJKLM WXCVBN

and in Germany, the change is even smaller:

QWERTZUIOPÜ ASDFGHJKLÖÄ YXCVBNM

but some other countries have keyboards which involve more extensive changes.

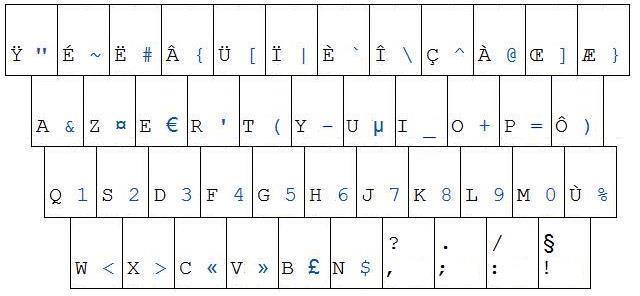

To avoid problems dealing with accented letters not in the standard 8-bit extension to ASCII, this image illustrates the Latvian keyboard arrangement:

There was also an old non-QWERTY keyboard layout for the Polish language:

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ^ ̧

ą ę ń ć ś ź ó = ́ `

|

Q H T C S Z R W J B :

.

X Ż N I E A O D Ł F ,

? %

V L P Y K U M G & _

And, in Turkey, the standard layout for typewriters there was promulgated after extensive study of the properties of the Turkish language and of typing efficiency:

In 1937, Portugal's dictator Antonio Salazar decreed the use of the following keyboard arrangement:

¶ § " ' ( ) / % & £ ª `

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 $ º ^

_ ´

- H C E S A R O P Z ~

! ;

? Q T D I N U L M X ,

:

Y Ç J B F V G K W .

which is apparently no longer in use in Portugal, that country having returned to a QWERTY-based arrangement.

In Belgium, the following keyboard arrangement, clearly developed, like the Dvorak keyboard, to permit efficient typing, was once in use:

1 3 4 5 6 7 8 §

* " è à & _ ( F Z X B !

2 °

é A E U - K G L M N P

¨ 9 /

^ O I Y : ç Q T R S C

: % + = ?

´ ) ù , W J D ' H V

but as it is not offered even as an alternate keyboard now for that country by computer makers, I can only assume that it, too, has fallen into disuse.

I have now found some more information on this keyboard arrangement. I had originally seen it in the array of Olympia keyboard arrangments shown in the book "Century of the Typewriter", but other than seeing that it was from Belgium, there was no other information.

Now, I have learned that this arrangement started life looking something like this:

( ! 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ¨ ) " A E U Z K G M L N P / & O I Y F ° Q T R S C _ § à è ù X W J D B H V ? é a e u z k g m l n p : ^ o i y f ç q t r s c ' = . , ; x w j d b h v -

on a Remington 2 typewriter, although the arrangement shown is that of of a later Smith Premium 4 typewriter.

It was invented by Alfred Valley - at the age of 17 - and this efficient keyboard arrangement enabled him to win a typing contest.

According to this page, this arrangement was available in Belgium as an alternative to the conventional French AZERTY arrangement for a span of fifty years, but it fell out of use before the Second World War, which is why it wasn't listed as an option for DOS or Windows.

The Olympia version, on a conventional four-bank typewriter with shift, is very close to that offered by L. C. Smith, but the one offered by Remington was slightly different:

3 4 5 6 7 8

" ' ( - è _ F Z X B

2 °

é A E U ) K G L M N P

¨ 9 /

^ O I Y ç : Q T R S C

: % + & ?

; ù = à W J D , H V

In France, in 1907, a committee devised an alternative keyboard arrangement as a reaction to perceived inefficiencies in the QWERTY keyboard as well; this keyboard existed in both a four-bank version:

§ ù / º " ( ) ç ? ! è é 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 & ¨ à Z H J A Y S C P G ^ _ % - X U I E Q R T N D ' ; : , . K W O V L M B F

and a three-bank version:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

à

Z H J A Y S C P G .

§ / " ( ) ? ! Fr œ è

'

X U I E Q R T N D é

& % - : ù ç _ + = º

; ¨

, K W O V L M B F ^

It was one Albert Navarre who led the effort to create this keyboard arrangement. It has fallen out of use, though, and a newer ergonomic arrangement, Bépo, is now considered for French.

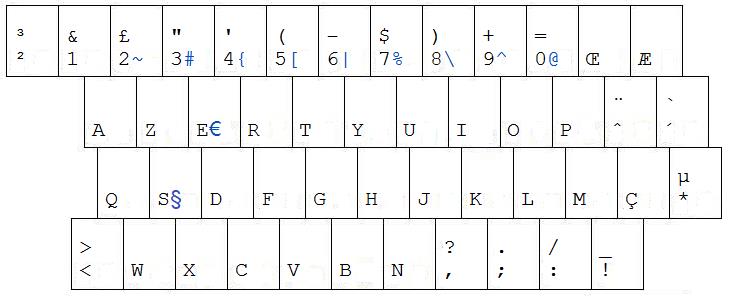

I had learned the new information concerning the Belgian keyboard arrangement, and of the alternate French arrangement, as the result of a recent news item (from 2016, and I began writing this shortly after I heard of it) to the effect that the French government is looking for a modification to the AZERTY keyboard currently in use.

Apparently, they're looking for something like this:

as the primary issue of concern is that the upper-case versions of French accented letters are not available on the keyboard, with another being the absence of guiellemets. So, to allow accented letters to take up a full key - as Ä, Ö, and Ü do on the German keyboard - it seems as if more special characters, and even the ten digits, will need to be accessed through the AltGr shift.

While I think that this is an entirely appropriate expedient in the case of a keyboard for the Armenian language, so that such a keyboard can have a reasonably small number of keys, to treat the French language in the same way does not seem reasonable. It elevates the importance of correct use of accents in French above practicality and convenience, and thus is likely to be faced with complaints and ridicule.

Of course, they may really be seeking something rather less radical than what I am showing above; something where the upper-case accents are at least available, even if not given the best or most accessible positions. So presumably the AltGr key would be used to reach them rather than the ten digits.

And of course, the possibility of something clever or original, such as the use of the Caps Lock key to switch between a conventional mode and one with the upper-case accented letters available should not be excluded.

Actually, on further reflection, I see that I am being quite unfair. If the macron and the circumflex can be applied as accents by means of dead keys, then the same can be done with the grave and accute accents, leaving only the three characters Ç, Æ, and Œ to have full keys, which requires only very minimal changes to the existing AZERTY keyboard, as follows:

And, as a bonus, the ten digits are now available as lower-case characters rather than upper-case characters.

However, the price of this is that additional letters, presumably the ones most frequently used, are no longer precomposed, but instead the accent must be typed separately. Since the original French keyboard includes four additional precomposed characters, à, é, è, and ù in addition to ç, which is retained, it's difficult to design a compromise keyboard where all of those precomposed characters are retained, with only making more special characters accessible by the AltGr shift as the price.

But not that difficult, since there are four keys available; three with special characters, the superscript 2 and 3, the asterisk and mu, the one on which I have placed the underscore and the exclamation mark, and the one on which I have placed the acute and grave accents, so the comma, period, and colon can be left alone, as well as greater than and less than on their key.

And so,

a keyboard that respects the French language can look like this.

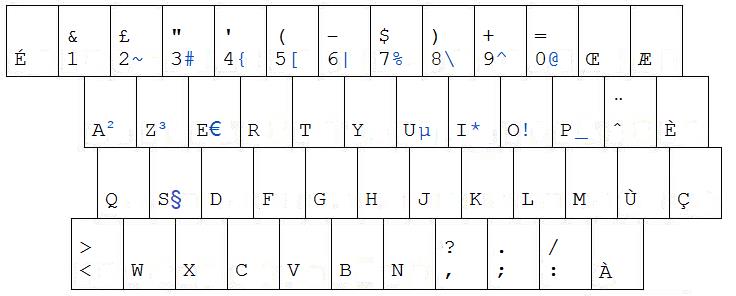

However, I see from this page that on April 2, 2019, AFNOR did reach the conclusion of its process, and a new standard NF Z71-300 for both the AZERTY keyboard and the BEPO arrangement, was published. So the actual new keyboard design (for the AZERTY keyboard) that they reached was:

However, this arrangement does not appear to achieve their stated goals. I suppose that Shift+AltGr can be used on it to access the accented capital letters. It may also be noted that the placement of the # and @ characters follows the Macintosh version of the AZERTY keyboard.

Because I based it on an illustration of the standard keyboard in the Futura typeface, some quote and accent characters are guesses on my part, not having sprung a few hundred Euros for the official standard; also, omitted from the diagram is an Alt character having the form of an "Eu" digraph on the H key, as I'm not sure what character that is supposed to be.

Ah, this other page explains that the Eu code is to be entered to precede other keys to allow entering additional characters from some other European languages. As well, it confirmed that my guesses for accents and quotes were correct. Also shown on that page are additional characters from the keyboard specification that aren't normally printed on the keys.

Just as alternate keyboards other than the Dvorak keyboard were designed in France and Belgium, there was also a German alternative keyboard for greater efficiency:

° § ℓ » « $ €

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 -

X V L C W K H G F Q ß

U I A E O S N R T D Y

Ü Ö Ä P Z B M , . J

this is the Neo keyboard, which is not shown completely here.

The following diagram shows three Russian keyboard arrangements of interest, along with three keyboard arrangements for Bulgarian, which (at least at present) uses the same Cyrillic letters as Russian:

At the top of the diagram is the old Russian keyboard arrangement for typing in the old orthography.

Originally, I omitted two of the additional letters used in the old orthography, as the keyboard image I found did not include them. More recently, having seen an image of a keyboard with an arrangement like that in the second diagram, but also with a V perhaps for writing Roman numerals, I took its position as a clue to deciding where those two letters might have gone.

One of those two letters, "izhitsa", which looks like a V, sometimes with a tail on the top right, was very rarely used; according to Wikipedia, by 1901 or thereabouts, only the Russian word for myrrh was consistently spelled using that letter. The other missing letter is "fita", which looks like the Greek letter theta, and which was used in many, but not all, Russian words derived from Greek in place of the normal Russian letter F which looks like the Greek letter phi. Wikipedia notes that some Russian words derived from Greek went and used T instead to replace theta.

The second diagram shows an early Russian keyboard for the new orthography, where the positions of the letters which were removed were simply reused; only the hard sign was moved.

The third diagram shows a modern Russian typewriter for the new orthography. Instead of moving other letters into the vacated spaces, the whole row of letters to the right of two of the vacated spaces is moved one position to the left, which changed the keyboard arrangement enough to require people to learn to type again.

The fourth diagram shows the modern standard Bulgarian keyboard arrangement.

The fifth diagram shows an example of the keyboard on a Bulgarian typewriter which predated that modern standard; the character "yerry" is handled differently, being available in upper-case on the older arrangement, and a couple of other letters are moved around: the letter F is almost exchanged with "yerry", but not in exactly the same position on the bottom row, and so "e oborotnoye" is moved over one position.

And then the sixth diagram shows a keyboard in which "yerry" is entirely omitted, but where an additional letter, "yus", unique to Bulgarian, is present in the position used for Q on a QWERTY keyboard, and, in addition, the letter "yat", also found in old orthography Russian, is also present.

Given the tragic events that are currently unfolding, I thought it to be inappropriate to continue including Russian keyboard layouts on this page if I omit the Ukrainian keyboard layout, so I have rectified that omission:

This chart is primarily based on a photograph of an old Ukrainian typewriter; its arrangement closely resembles one of the transitional new orthography Russian typewriters shown above.

In Ukrainian, the letter resembling the Greek gamma is not pronounced as G, as it is in Russian, but instead as H. Unlike the Latin I, the I with diaresis, and the forwards rounded E (unlike E oborotnaye, shared with Russian), one additional Ukrainian letter, a modified form of the gamma-like letter which is pronounced as G, was not on that typewriter.

I did see it on one image of an old Hermes typewriter, and its locatiion was at least close to the key I had left on which to place it in the diagram.

This modified G happens to have an interesting history.

It first appeared in the Peresopnytsia Gospel from the 16th Century. This historic document was used as the Bible to swear in the presidents of the Ukraine ever since the fall of the Soviet Union.

It reappeared in one of several competing orthographies for Ukrainian in 1886, the Zhelekhivka alphabet of 1886. In the Soviet Union, in 1928 the first uniform standardized orthography for Ukrainian, the Skripnykivka alphabet, included this letter - and then it was removed from the Ukrainian orthography by the order of Stalin in 1933, not to return until 1990. Ukrainians in the diaspora, however, continued to use the older orthography with this letter, of course.

While in 1886, there were about 300 Ukrainian words with this letter, today it is chiefly used for words of foreign origin to indicate their pronounciation, and so this act of Stalin appears to have left its scars on the way some Ukrainian words are pronounced.

It should be noted that this is not the keyboard arrangement used for Ukrainian today on the computer. Obviously, all ten digits are required to be present on the keyboard, for one thing (an issue I am about to address in the very next paragraph, as it is). As the European-style keyboard is used for Ukrainian, the letter G ended up being placed on the key between the last letter of the alphabet (on the Ukrainian and Russian keyboards as well as our keyboard for English!) and the left-hand shift key on this form of the Ukrainian keyboard - at least for Windows. On the Macintosh keyboard, it is instead on the far right-hand side of the keyboard, on the home row.

Although Belarus is also on the wrong side of the conflict in Ukraine, I do not feel it inappropriate to add a keyboard for Belarus at this time:

because, to my mind, Belarus, as a country, is the same as Ukraine; only its fate was different: it remained under the heel of one of Putin's puppets, while Ukraine rebelled against the one assigned to it. In addition, in present-day Belarus, due to Stalin's movements of populations, the Belarusian language is hardly used, Russian being overwhelmingly the language of daily life.

The keyboard is basically the Russian keyboard, but with the unique Belarusian letter for W, a U kratkoye replacing shch, and with the same Latin-like I as Ukrainian.

Just as on many English-language typewriters, one had to use the lowercase L for the numeral 1, note how both the capital letter O and the Russian capital letter for Z are used for numerals, 0 and 3 respectively. This was also done on many Armenian-language keyboard layouts:

The diagram above shows the Armenian-language keyboard layouts offered by the Royal, Olympia, and Underwood companies respectively, followed by my attempt to reconstruct the keyboard arrangement of typewriters used in Soviet Armenia, based on a comment that Microsoft had mixed up two letters in their Eastern Armenian keyboard, and some inferences of my own concerning numbers and punctuation. Note that the arrangement of the letters matches that of the Olympia typewriter in part.

Olympia offered two variations of their Armenian keyboard; the other one is the arrangement depicted on the top of this diagram:

While that arrangement is not too much different from the other one of theirs depicted above, it more closely resembles the second arrangement in this diagram; this one, found on a typewriter made by Royal, while it resembles the Olympia arrangement more than their own, follows the Underwood one in avoiding replacing the digits 2 and 3 by the Armenian letters that resemble them - and, thus, is a potentially more useful keyboard arrangement in our computer age.

If one took the Eastern Armenian keyboard and modified it in the same way that this arrangement by Royal modified the Olympia one, one could get a keyboard like this:

based on the physical layout of the Japanese keyboard, but with a normal spacebar. Unfortunately, Armenia is too small a market for manufacturers to feel that even so small a degree of retooling for just that market would be worth it.

Given that keyboards without enough room for the Armenian alphabet and the ten digits seem to be inevitable, I would at least recommend the following two measures:

rather than using the Alt key to access digits on the top row.

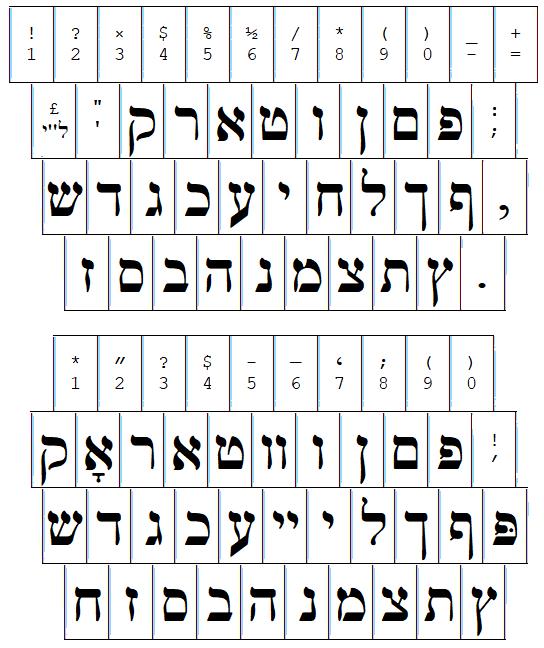

A case where languages sharing the same alphabet used related but different keyboards is shown here:

with a Hebrew keyboard at the top, and a Yiddish keyboard at the bottom.

The relation between these keyboards somewhat resembles that between the Russian keyboards shown earlier for the old and new orthographies.

This article discusses the only typing instruction book written for the use of speakers of Yiddish; it notes its interesing choice of practice texts. Also noted, though, is an unfortunate characteristic that limited its usefulness;

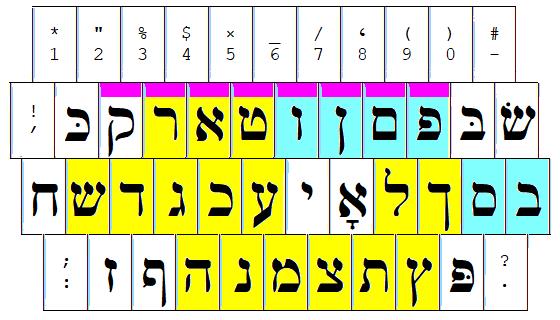

instead of being based on one of the standard keyboard arrangements in existence for Yiddish typewriters, the author, Tobias A. Jonas, based it on a keyboard arrangement which he designed to be more efficient, something like the Dvorak layout. However, this keyboard arrangement was not designed completely from scratch; the keys highlighted in color show horizontal blocks of keys that were taken from the standard Yiddish keyboard without change. As the Hebrew keyboard is closely related, for the most part, the matching blocks of keys are the same, except that in the top row of letters, a longer contiguous horizontal block of corresponding keys is present, as shown by the purple highlighting at the top of the keys.

In fairness, it should be noted that the differences between this keyboard and the standard Hebrew keyboard may be smaller than they might seem, since the recommended finger positions for touch-typing on this keyboard differ from those which are the current standard for a QWERTY layout. I have been able to prepare the illustration below to show this:

The illustration of a Hebrew keyboard at the top is of that of a Selectric typewriter. A specialized Selectric element was also made to allow typing in Yiddish, and typing of Hebrew with points. Its layout is illustrated here:

although I may have made some errors in drawing my version of it.

This element was designed by Hugh Denman of Queen's University in Belfast, with funding provided through the League for Yiddish donated by the Meyer and Tzippe Fruchtbaum Foundation for Jewish Culture and by the Judah Zelitch Charitable Trust. Apparently, this is the Hugh Denman who went on to become the Ben-Zion Margulies Lecturer in Yiddish Studies at University College, London.

As there are 85 characters in the Cherokee syllabary, and 88 positions on the original Selectric element, it was possible for the Cherokees themselves to go to Camwil and have a custom element made for their language.

Canada's Inuit were in a somewhat more difficult situation. Here, the creation of a Selectric typeball for their language was supported by the Canadian government, and so it was done at IBM itself.

But in the syllabic writing system for Inuktitut that was in place at the time, there were 48 basic syllabic symbols representing twelve consonants combined with four vowels, and 9 additional symbols representing final consonants, as well as one other overstruck symbol for vowel lengthening.

Unlike Cree, Inuktitut only used three different vowel sounds, but the common "ai" dipthong made use of the fourth vowel.

It turned out that there were not quite enough spaces on the element for all the characters that were needed. So the writing system was changed to require the second vowel in that dipthong to be written out; but two new consonant symbols were added, leading to a net savings of only four characters.

Another difficulty that was faced was that while the vowel-lengthening symbol was easy enough to use if the Inuktitut element was used on a Selectric typewriter fitted with the appropriate dead keys for using a French-Canadian element, and possibly with the Dead Key Disconnect feature to allow it to be used for English as well, in many places where it was used, Selectrics originally intended only for English typing was what were available, requiring extra backspacing when typing.

In the infancy of the typewriter, many different manufacturers had their own keyboard arrangements, such as the DHIATENSOR arrangement used with the Blickensderfer shown above. And many more efficient alternatives to the QWERTY keyboard have been proposed over the years, and new ones are still being invented. Even programs to begin with a starting keyboard layout and make changes to it to produce a more optimum keyboard are offered by more than one site.

But, of course, the only more efficient keyboard arrangement to achieve any significant recognition is the Dvorak keyboard layout:

7531902468= ?,.PYFGCRL/ AOEUIDHTNS- ,QJKXBMWVZ

in its original form, and

1234567890[] ',.PYFGCRL/=\ AOEUIDHTNS- ;QJKXBMWVZ

as commonly used today.

While I do feel the prospects for any simplified keyboard layout other than Dvorak are quite dim, still, I will note that if I were to approach the design of a more efficient keyboard in a simplistic fashion, I might come up with something like this:

,.HSYFCMWG OIAEULTNRD ;/JXZQKVBP

based primarily on individual letter frequencies, but also giving the letters H, S, and Y to the left hand because they are somewhat more likely to be found together with other consonants than many other consonants. This is also slightly true of Z, while Q invariably precedes U, confirming the decision to follow frequency instead of alphabetical order.

However, none of the alternative keyboard arrangements I've encountered seem to resemble this one very much, so presumably I have not given enough weight to some more sophisticated variables impinging on typing speed.

Of course, on the theory that just about anything is better than QWERTY, the arrangement:

,.KLMNOPQR ABCDEFGHIJ ;/STUVWXYZ

would at least be easy to memorize; and, by departing slightly from plain alphabetical order by putting the first letters in the middle row, it still makes an effort to make the most frequent letters the easiest to reach. Of course, swapping the two letters D and E would be an obvious further improvement. (Could the result be called the abecedarian keyboard?)

Or, one could go with:

,CGUVWQ789 .DHK;/P456 AEILMNORST BFJXYZ0123

to make use of the regular spacing of the first three vowels in the alphabet, but it isn't really clear that the form of alphabetic order visible in this arrangement will really help all that much in memorizing it. Sneaking a numeric keypad arrangement for the numbers into the design is, at least, interesting.

But, as noted, it is enough trouble to bother with any keyboard arrangement other than QWERTY for improved typing speed; at least Dvorak has a modicum of recognition, and would seem to be the only alternate keyboard arrangement worth bothering with on a normal keyboard. Of course, while this is true for regular keyboards, for other types of keyboard, arrangements such as the FITALY keyboard for stylus entry, or the ergonomic Maltron keyboard, or a pure alphabetic arrangement of keys for devices with keypads too small for touch-typing, can have a valid place.

The keyboard on the IBM Personal Computer was designed to offer an important feature to avoid frustration while typing. The keyboard was constantly scanned by sophisticated circuitry which sent one code to the computer when a key was depressed, and another code when the key was released.

Quite early in the life of the IBM PC, someone made a keyboard overlay and software so that two rows of keys on the PC keyboard could be used as a piano keyboard, thanks to this feature.

Could someone make software for the PC so that one could, by pressing several keys at once, type, say, an entire English syllable?

So, to type the word "strengths", from left to right on the keyboard, one might press the left "s" key, the "t" key, the "r" key, the "e" key, the "ng" key, the "th" key, and the right "s" key.

Some keyboards have been made like this.

Of the three keyboards I will note of this type, the first is the Stenotype keyboard, used for court reporting. It is described in U.S. Patent 1,143,160, from the year 1915. Alice M. Anderson is the inventor. This keyboard is noted by (1) in the diagram at the left.

Four keys represent vowels, and they are operated with the thumb; this is a factor common to the two other keyboards I will discuss later, and as it seems to me that having the thumbs operate the vowel keys is an unavoidable feature of a syllable chord keyboard, it seems to prevent providing such a keyboard using only software.

This type of keyboard remains in use for court reporting to the present day. As the Wikipedia article on it notes, individual users of this type of keyboard may use their own combinations of letters that do not normally occur together in syllables to stand for consonants not shown on the machine. Because this means the use of this type of keyboard is of a personalized nature, I was not surprised that I did not initially turn up references to attempts made to adapt it to computer data entry, but later I did find that at least one company, Advantage Software, appears to have developed closed-captioning systems, and other related products, based on this type of keyboard.

Also, the asterisk appears to be used to indicate that voiced consonants are to be replaced by their unvoiced counterparts.

In Britain, a different keyboard design is often used for court reporting. This keyboard is known as the Palantype keyboard. This keyboard is described in U.S. Patent 2,318,519, issued in 1943. The inventor was Clementine Camille Marie Palanque. It is indicated by (2) in the diagram at left.

As there were three rows of consonants instead of two rows, the key combinations for the less used letters were standardized on this keyboard, and so while in its original form, each syllable was represented by a row of letters each of which was either present or not in its own position in the row, as with the Stenotype, electronic versions of this keyboard were made which used a large dictionary of the words of English to produce output with conventional spelling. The BBC used this method for real-time closed captioning of television shows, and keyboards of this type are also used in Britain for the hearing-impaired to communicate. The company supplying keyboards of this type in Britain, Possum Controls Limited, recently closed down, but licensed its technology so that it would remain available to hearing-impaired individuals there.

The dot indicates that the vowel should be long, and the plus signs on each half of the keyboard indicate that the unvoiced consonant on that side of the syllable is to be replaced by its voiced counterpart.

Still later, another type of keyboard, first known by its original trademark, Velotype, and currently available under the Veyboard name, was developed. This is described in U.S. Patent 4,804,279, granted in 1989. Its inventors were Nicolaas M. Berkelmans and Marius Den Outer, and was assigned to the Dutch company Special Systems Industry B.V., and is indicated by (3) in the diagram at left.

This keyboard also operates on the basic principle of the fingers of the left hand indicating the consonants before the vowel, the thumbs the vowel, and the fingers of the right hand indicating the consonants after the vowel. But it was not designed for court reporting, and was designed from the beginning to facilitate entry of text with normal spelling. The patent describes how the interpretation of the keys of the keyboard is modified so that it can be used with English, Dutch, or German.

While it was originally sold as a generally useful keyboard for anyone who would like to type text on a PC more quickly, limited demand has led to its price going up, and the information I have seen implies that its remaining users are largely Dutch TV stations, for their closed captioning. It had been used in the U.S. and other countries both for that purpose and for other purposes in its heyday.

Like the Palantype, this keyboard also had three rows of consonants for the fingers. Except for A and U, it had two complete sets of vowels so that the spelling of dipthongs could be indicated, but they are located where a finger, not the thumb, reaches them.

Syllable chord keyboards appear not to have been particularly successful, except in niche applications, and this is, of course, not particularly surprising in view of the amount of training that is required to use them successfully.

It occurs to me, however, that a conventional ergonomic keyboard design could be modified by splitting the space bar into two keys, and adding some keys below it and perhaps above it as well to allow the keyboard to optionally be used as a syllable chord keyboard. With four rows of keys for the fingers, instead of two or three, perhaps the design could be simplified so as to reduce the learning curve significantly, even if that meant the typing speeds achievable would not be quite as high as with previous designs.

The large keys for changing capitalization and spacing on the Velotype or Veyboard are meant to be operated by the forearms; to have such keys on the type of keyboard I am describing, and yet have them out of the way when the keyboard is used conventionally, one could have a bar that swings out of the way, linking two small keys (which could be mechanically linked underneath, like the sides of a space bar on many computer keyboards).

Thus, one would start from a typical ergonomic keyboard design:

modify it so that the amount by which the rows of keys are staggered is uniform:

change the shape of the keys, so that it is possible for one finger to easily press two keys that are adjacent in the same column, and add the additional keys required for chord keyboard usage:

and finally, develop the arrangement of keys required for such usage:

The home locations of the fingers would remain the same as when the keyboard is used conventionally, on the keys that on the QWERTY layout correspond to (A S D F) and (J K L ;). Up to six consonant sounds might occur in a syllable, and the fingers that indicate them would be (A)(SD)(F) before the vowel and (J)(KL)(;) after the vowel. So most consonants would be indicated by the (SD) and (KL) fingers; the other fingers would be used for those which combine before or after other consonants.

If necessary, the fingers which rest on the S and K keys would be used to "shift" the meanings of the keys struck by the fingers from the D and L keys respectively to allow more than fourteen consonants to be present in the middle position of a consonant cluster.

Some combinations of consonants, such as TH and NG, would be treated as single letters; this would also be true for QU on the left-hand side of the keyboard.

My goal is to make a chord keyboard that can be used as a normal keyboard, and which is simple to learn, to allow people to try getting started with this approach without a large up-front investment in effort.

Copyright (c) 2007 John J. G. Savard