I mentioned The Landlord's Game on the preceding page. As some visitors to this page may not be familiar with the history involved, while there are other pages out there which cover it in more detail, I thought it would be worthwhile to briefly mention it here as well.

You may have heard that the game of Monopoly® was invented by Charles Darrow. However, that turned out not to be entirely accurate.

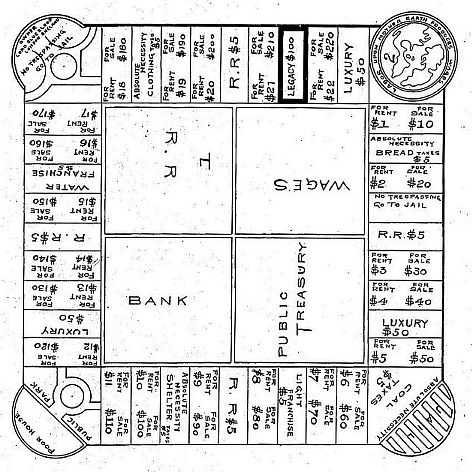

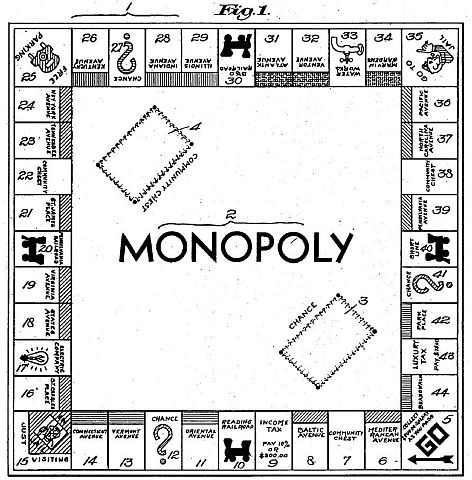

The story begins with U.S. Patent 748,626, issued on January 5, 1904, to Elizabeth J. Magie. On the right is the illustration of the game board from that patent.

It may look a bit familiar.

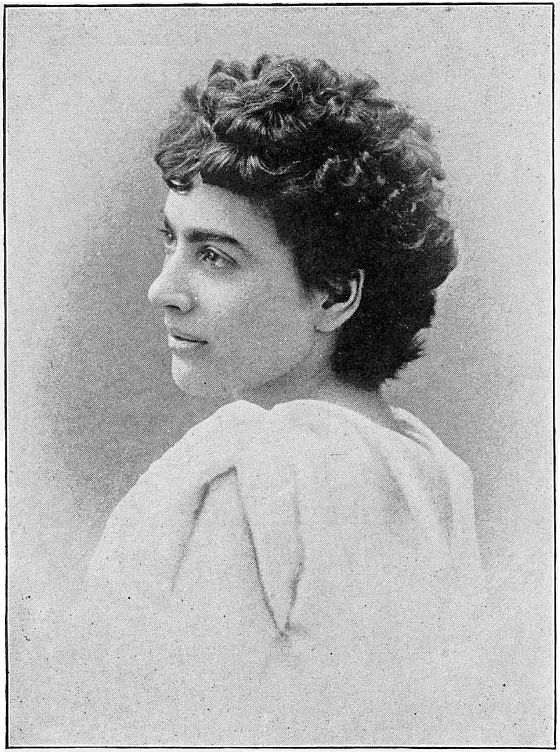

On the left (or, perhaps, below, depending on how wide your browser window is) is a photograph of Elizabeth J. Magie, from a volume of self-published poetry that she wrote, from the year 1892.

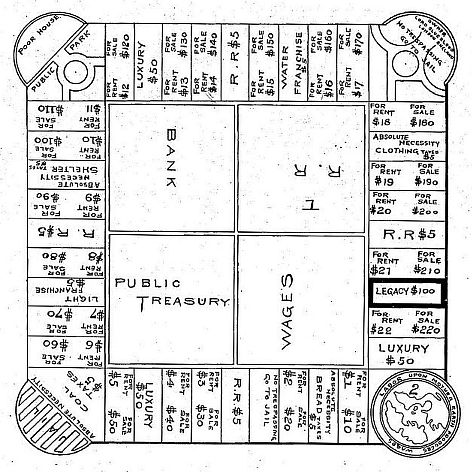

If we rotate it clockwise by 90 degrees, and compare it with the illustration of the game board in U.S. Patent 2,026,082 (issued on December 31, 1935), the resemblance is even clearer.

This wasn't a case of out-and-out piracy, however. Charles Darrow no doubt had never even heard of Elizabeth Magie.

The Landlord's Game, as originally invented by Elizabeth Magie, was intended to illustrate the single-tax theory of Henry George, by having two sets of rules, by which players could compare the situation of the present day, with unbridled free enterprise, with something better and more fair.

It was manufactured and sold commercially, and it even had one set of "Chance" cards in its 1906 version, with the spaces indicating one such card was to be drawn replacing the "Legacy $100" space, and one of the three "Luxury $50" spaces, the one nearest the Poor House and the Public Park. But it was never a roaring success, and so not many copies were sold. However, it was successful enough that an abridged version was sold in Britain in 1913.

Also, it was possible to increase the rent for a property by placing houses on it, but the properties weren't yet organized into groups that had to be completed before this could be done. The rent was increased by $10 for each additional house, rather than increasing as quickly as it did in later versions.

However, in at least some parts of the United States, some people who saw the game at a friend's place, and couldn't purchase a copy, made their own boards and pieces.

This led to the game becoming a folk game; and, as a folk game, it underwent changes. One folk version of the game from 1927, that played at the home of Roy Stryker, is documented as having the properties organized into groups, as they are today; the rent doubled when all the properties of a group were owned, and then doubled with each additional house, up to four, on a property. Thus, at that point at least, the essential features of the modern game were present.

Assigning colors to the groups of properties, using the names of streets and neighborhoods in Atlantic City, and even the spelling error that changed Marven Gardens to Marvin Gardens all happened at that time.

And it was a folk version of the game that Charles Darrow encountered, on which he based his submission to Parker Brothers, with no knowledge of the game's actual existence as something that was once offered for sale commercially, or of its inventor. An even more extenuating circumstance was that not only was he unemployed during the Depression, like many others, but in addition he had a son who was cognitively impared due to having been ill with scarlet fever, and far more money than he could afford was needed to provide him with proper care.

Charles Todd, at whose home Charles Darrow learned of the game, typed up the set of rules for it that Charles Darrow used. He learned of the game from his neighbors, Ruth and Eugene Railford, but he (Charles Todd) in copying the board made the historic mistake of changing Marven Gardens to Marvin Gardens.

It was another friend of Charles Darrow, Franklin Alexander, who added artwork to the board, drawing the prisoner in Jail and the policeman on the Go to Jail space.

However, Monopoly® was not even the first commercial game based on the folk game which derived from Elizabeth Magie's invention. In 1932, the game of Finance®, which was derived from the folk game by one Dan Layman, was sold by Electronic Laboratories, later Knapp Electric. He actually considered naming the game Monopoly, but he chose another name as he felt there would be a difficulty in trademarking that name. This game was sold to Parker Brothers, which brought out a simplified real estate trading game under the name, as an alternative to Monopoly®.

This seems to imply that we can't even say that, if it weren't for Charles Darrow, the game of Monopoly® wouldn't have become available to everyone, instead of just a lucky few who had heard about it by word of mouth.

However, on balance, I think that this isn't quite true. The version of the game being played at Charles Todd's home had at least one important feature that Finance® lacked. The latter game did have color-groups of properties, and houses and hotels. But all the squares on the board were one color or another. The properties in a single color group, however, were also indicated by a distinctive symbol, with nothing similar being on any other kind of space.

Having a white background for the spaces, with the color for each color group in a narrow area at the top of the space, was a great improvement, as then the properties in color-groups were readily distinguished from other spaces, and the colors used weren't restricted to those against which lettering could be readable.

In the game of Finance®, as originally sold before being acquired by Parker Brothers, some of the properties, such as Broadway, still had names from the 1906 version of The Landlord's Game. But others were different. One group of properties represented an Irish neighborhood, consisting of Maguire Street, Delancey Street, and O'Leary Avenue.

The color group immediately preceding that one on the board consisted of Goldberg Square, Epstein Road, and Cohen Boulevard.

In 1932, this may not have been considered a problem. Even in, say, 1961, long before political correctness or being "woke" had become a thing, however, I really feel that this would not have been something that people would have been comfortable with.

Thus, the change to street names derived from Atlantic City, in my opinion, also benefited the wide acceptance of the game in the form in which it became most widely available.

Also, briefly in 1935, before publishing Monopoly, Parker Brothers published a very similar game by the name of Fortune. It even had Chance and Community Chest cards; however, passing Go paid $250 instead of $200. In some ways, the game looked more like Finance than like Monopoly, but it did divide the properties into color groups.

While this photo, showing Elizabeth Magie Philips examining a folk Monoply board, a later commercial version of The Landlord's Game, and a modern Monopoly® board from Parker Brothers appeared in the January 28, 1936 issue of the Washington Star, her connection to the game of Monopoly® became obscure and forgotten, until it ended up being researched and unearthed by Ralph Anspach in conneection with a court case in which he defended his right to produce the board game Anti-Monopoly.

On the right is another image of Elizabeth Magie, also from the Washington Star, from its October 22, 1906 edition, showing her as she appeared close to the time of The Landlord Game's original invention.

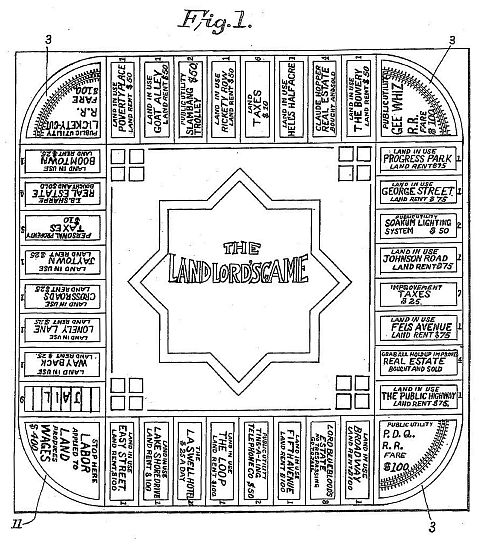

At right is shown the diagram of the board of the later version of the game appearing in the photograph, which bears less resemblance to its modern sibling than the original. The news article resulted from Elizabeth Magie Phillips contacting the newspapers after she learned of the existence of the game of Monopoly®; she had not been aware, when she sold the rights to The Landlord's Game to Parker Brothers, that they were purchased in order to defend that game, rather than because they were interested in her own game in its original form.

While Ralph Anspach eventually won his court case, this only took place on appeal; the trial judge found against him, despite the facts presented on the origin of the game, because the issue was the game's trademark, rather than one of patent rights; the appellate court, however, found grounds under trademark law to rule in his favor.

While the policeman on the "Go to Jail" space, and the prisoner in Jail, appeared on the Monopoly game boards made by Charles Darrow prior to the game being sold to Parker Brothers, the character now known as Mr. Monopoly (this new name being introduced in 1999) did not appear in the game until 1936, in revised artwork for the Chance and Community Chest cards. A different tycoon, without hat or moustache, appeared on the game box, from 1935 right up until 1952, with the modern character appearing on the game box in 1954.

It was only learned in 2013 that the artist who first drew him for Parker Brothers was one Daniel Fox.

His original name, Rich Uncle Milburn Pennybags, was revealed in 1946, when a related game, Rich Uncle, about the stock market, came out. (Incidentally, The Beverly Hillbillies, with the banker Milburn Drysdale as an important character, first aired in 1962.) This game had a set of cards with random events on them; the events were in the form of headlines for a fictitious newspaper... The Daily Bugle. So that's where the inspiration for J. Jonah Jamieson's newspaper in the Spider-Man comic book came from!

Although this game concerned the stock market, it is unrelated to the game Stock Exchange, which was originally made by a third-party company, Capitol Novelty Company, for use with Monopoly, Finance, or Easy Money. Later, it was bought by Parker Brothers, which sold it as an add-on for Monopoly specifically.

This game included additional Chance and Community Chest cards, stock certificates, and a new square to cover and replace the Free Parking square on the board.

Most people who play Monopoly® today are familiar with the use of metal tokens as game pieces, in shapes that resemble items that might be found on a charm bracelet. During wartime, and for some time after World War II in Canada, sets included wooden pieces, lathe turned in different abstract shapes and painted different colors, instead.

As well, one might encounter reference to sets including "Grand Hotels". This didn't mean that there was a third item one could place on a property to increase rent, after houses and ordinary hotels. Rather, before houses and hotels were made from plastic, they were instead made from wood, and for a period of time, the words "Grand Hotel", and a picture of a doorway and windows were printed in gold on the wooden hotels.

It was noted above that the space "Marvin Gardens" on the traditional board was spelled incorrectly; the street in Atlantic City is actually Marven Gardens.

There is another space on the Monopoly board that is misnamed as well.

The Pennsylvania Railroad, the Reading Railroad, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad are all real railroads with storied histories that reached Atlantic City.

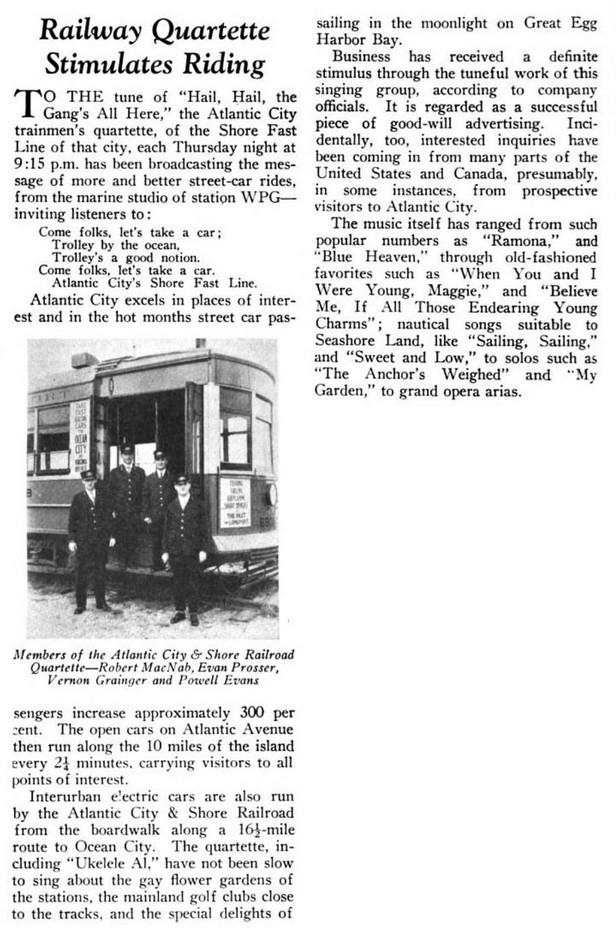

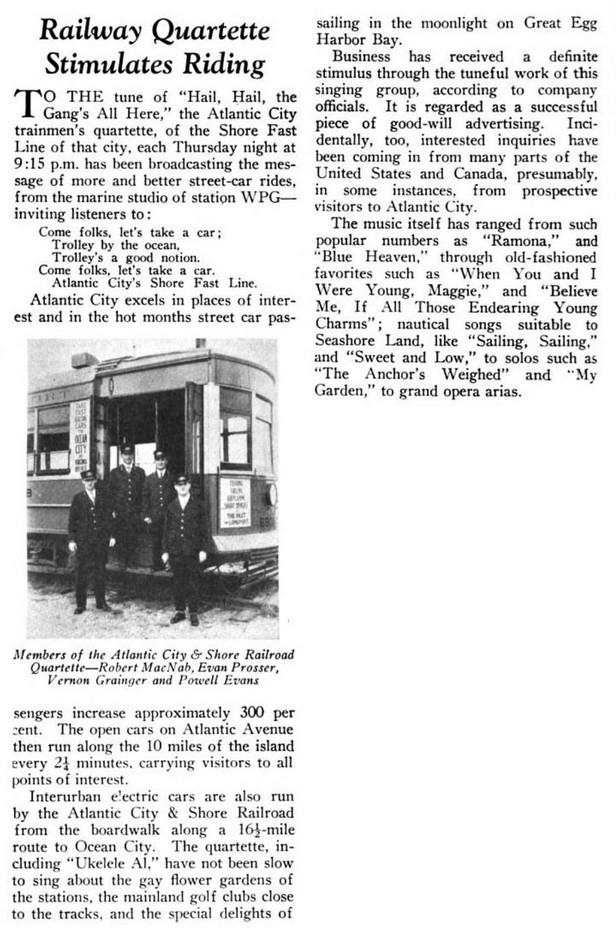

There was also a commuter train serving Atlantic City, known as the Shore Fast Line, operated by the Atlantic City and Shore Railroad. It is this which is referred to as the "Short Line" on the Monopoly board.

I managed to find this old news item referring to that rail line, which includes a picture of one of its trains:

The music of the 1890s, which decade is known as the "Gay Nineties", is often sung by male vocal groups with four members, known as "Barbershop Quartets", but this type of musical ensemble is not confined to the tonsorial industry; railroads had them too!

Incidentally, since "My Blue Heaven" by Walter Donaldson and George A. Whiting dates from 1927, that probably is the song referred to as "Blue Heaven" in this article from the October, 1928 issue of AERA, the monthly magazine of the American Electric Railway Association.

In other trivia about the names of properties on the Monopoly board:

According to one account, the name for Mediterranean Avenue was chosen by Charles Darrow himself; the folk game as he had encountered it had another avenue in Atlantic City in that spot on the board, Arctic Avenue. However, according to Wikipedia, this change was instead made by Charles and Olive Todd, the people in whose home he encountered the game. Recently, Atlantic City renamed one block of Arctic Avenue after Rita and Anthony Mack, who owned and operated the McDonald's locations of that city for many years.

Illinois Avenue was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in 1988.

St. Charles Place no longer exists, a casino having been built where it once was.

A proposal was made in the 1970s to rename Baltic and Mediterranean avenues in Atlantic City, but it eventually was abandoned after outcry by Monopoly fans.

In the meantime, on the Monopoly board, this year in 2025, Oriental Avenue was replaced by Rhode Island Avenue, also a real avenue in Atlantic City, doubtless to respect today's sensitivities.

In fairness to Parker Brothers, given that this page is largely about how there most famous and popular game was stolen from Elizabeth Magie, I should mention another game, Touring (the famous Automobile card game), of which Parker Brother's ownership is unquestionable. It was designed by William Janson Roche, and first sold by the Wallie Dorr company in 1906, but was sold to Parker Brothers in 1925.

The deck of cards used for the game included mileage cards in various denominations, hazard cards, and "Go" cards. Players played mileage cards to reach a set destination, or they could play a hazard card to stop an opponent, who would then have to play the counter to the hazard, and a "Go" card, before being able to play mileage cards again.

This may sound familiar. In 1954, Edmond Dujardin invented the game of Mille Bornes, which had game mechanics very similar to those of Touring, but with one important addition: there were also safety cards, which when played made a player immune to a particular type of hazard: and, in addition, if held in the hand at a time playing the hazard to the player is attempted, can also be immediately played to counter it in a coup fourée.

But there were no lawsuits, and indeed Parker Brothers were very good sports about this, selling Mille Bornes to the North American market themselves under license and discontinuing their own game.

Of course, by 1954, the patents and copyrights from 1906 would definitely have expired.

Monopoly, Finance, Rich Uncle, Stock Exchange, Touring and even The Landlord's Game are trademarks of Hasbro as it currently owns Parker Brothers; Easy Money is also a trademark of Hasbro as it currently owns Milton-Bradley. Stock Ticker is a trademark of Copp Clark.

The Landlord's Game is currently a registered trademark of yourPlay LLC, owned by Thomas Forsyth, who made and sold a modern reproduction of the 1906 game. His original reproduction of the 1906 game was, however, titled Progress and Poverty; apparently, it is only afterwards that he acquired the rights to the original name. According to his web site, at least as I understood what I read there, the trademark lapsed when Hasbro purchased Parker Brothers because while Parker Brothers had a de facto or common-law trademark to the name The Landlord's Game from having published a version of that game, it had never registered its trademark; thus, as Hasbro didn't also publish this game, Parker Brothers only having published it very briefly, it became available.

Spider-Man is a trademark of Marvel Comics Group.

Mille Bornes is a trademark of Winning Moves.