There are twelve inches in a foot, and sixteen ounces in a pound. Three feet make a yard, four quarts make a gallon.

While these various scale factors are what has led to the complicated structure of the traditional English system of measurement, they also show that a need was felt to be able to easily divide quantities up, without resorting to fractions, into halves and thirds and quarters.

Dividing something into quarters takes two places of decimals, not just one, and dividing something into thirds is not possible in decimals. Thus, the metric system of measurement, relying exclusively on factors of 10 to relate unis of different size, doesn't provide units that can be divided up as well as it seems to be desired to divide up units of measure.

How could one have a system of measurement that offers the divisibility found in traditional systems of units, and yet one which conforms in the kind of simple and direct manner to arithmetic that the metric system conforms in?

There is one simple answer to this, one way in which these two conflicting requirements can be reconciled. We can change the way we do arithmetic, using the duodecimal system instead of the decimal system.

Of course, that is such a far-reaching change that it is extremely unlikely ever to happen. Yet, it's true that the prefixes kilo-, mega-, giga-, and so on now carry a double meaning, since two to the tenth power is 1,024, which is not far from a thousand. Unfortunately, one has to wait until twelve to the thirteenth power to get 106,993,205,379,072 - which exceeds ten to the fourteenth power by seven per cent - so there is no trivial way for the duodecimal system to serve as an approximation to the decimal system in an analogous manner.

Still...

1 12 2 144 3 1 728 4 20 736 5 248 832 6 2 985 984 7 35 831 808 8 429 981 696 9 5 159 780 352 10 61 917 364 224 11 743 008 370 688 12 8 916 100 448 256 13 106 993 205 379 072 14 1 273 817 464 548 864 15 15 407 021 574 586 368

12 to the fourth power is approximately 20,000; 12 to the sixth power is approximately three million;

Still, one can briefly consider how this might allow the traditional system of English measures to be transformed so as to become as rational as the metric system.

As there are twelve inches to the foot, both these units could fit directly into a duodecimal system of weights and measures - using the prefixes proposed by Tom Pendelbury, who proposed a more sophisticated duodecimal meaurement system (and there was also the Do-Metric system, which is not the same as this one either), a brief table of correspondences can be exhibited:

quedrafoot 3 miles 7 furlongs 4 chains 4 yards trinafoot 2 furlongs 6 chains 4 yards dunafoot 2 chains 4 yards zenafoot 4 yards; 2 fathoms foot foot inch inch zeniinch line; 1/4 barleycorn; 1/2 pica duniinch 1/2 point

Thus, a quedrafoot is just a bit less than four miles (there are eight furlongs to a mile, ten chains to a furlong, and 66 feet to a chain). The printer's units shown, the pica and the point, are predicated on the Selectric Composer point of exactly 1/72 inch.

There are sixteen ounces to a pound. However, the avoirdupois pound is often considered to be a unit of force (with the slug as its associated unit of mass) although it can also be considered a unit of mass (with the poundal as its associated unit of force). Also, an avoirdupois pound is equal to 7000 grains.

On the other hand, the troy pound, used mainly to specify the price of gold, is clearly a unit of mass, just like the kilogram, there are twelve troy ounces to the troy pound, and a troy ounce is 480 grains. So this is the English customary unit of weight that would be well suited to a duodecimal system:

troy pound troy pound troy ounce troy ounce zeniounce 40 grains duniounce 3 1/3 grains

The metric system did not attempt to modify how we tell time; the hour, the minute, and the second remain the units of time, with the second being the basis of other metric units.

However, since there are 24, twice twelve, hours in a day, it would seem that the opportunity of making the clock fully duodecimal does exist. Thus, the units of time might be:

zenahour 1/2 day hour hour zenihour 5 minutes dunihour 25 seconds trinihour 2 1/12 seconds

Note that while there are twelve trinihours in a dunihour, the trinihour is a bit over two seconds and the dunihour is a bit under half a minute, so trinihours would still take the place of seconds and dunihours the place of minutes.

Just as the meter, the kilogram, and the second allow the other units of SI to be derived, or the centimeter, the gram, and the second allow the units of the alternative cgs system to be derived, one can derive a complete system of units from the foot, the troy ounce, and the hour; replacing the troy ounce by the troy pound, and the hour by the trinihour, allows the magnitudes of the units to remain in somewhat the same ballpark as those in the SI or MKS system.

12 trinihours = 25 seconds; 1 trinihour = 2.08333... seconds 1 troy pound = 5760 grains = 373.2417216 grams = 0.3732417216 kilograms 1 foot = 30.48 centimeters = 0.3048 meters troy_pound foot / trinihour^2 = 0.4937676942 Newtons = 4937.676942 dynes troy_pound / foot trinihour^2 = 5.314871227 Pascals troy_pound foot^2 / trinihour^2 = 0.1505003932 Joules = 150500.3932 ergs troy_pound foot^2 / trinihour^3 = 0.3135424858 Watts

While there are 5,280 feet to a mile, and therefore 1,760 yards to a mile, and, thus, 1,728 yards to a mile instead, with 1,728 being twelve to the third power, is not very much different, going over to base-12 numeration is rather too extreme a measure to take to make the British Imperial system of measures comparable to the metric system in rationality.

Could the British Imperial system of measures be modified slightly, to remove its worst parts, so that the additional complexities of using it instead of the metric system would not be particularly severe?

I think that is possible, although it's quite unlikely that even a rationalized Imperial measure system could replace the metric system at this late date.

In the case of the mile, the solution is obvious. Take the literal meaning of the Roman unit, one thousand paces, and thus define a new, rationalized mile to be 6,000 feet, or 2,000 yards.

Twelve inches to the foot, three feet to the yard, and two thousand yards to the mile; that is a small number of multiplications, hardly worth complaining about.

In the case of units of mass, sixteen ounces to the pound, and two thousand pounds to the ton, are also not that much. However, 7,000 grains to the pound (avoirdupois), but 480 grains to the pound (troy) with four troy ounces to the troy pound is definitely annoying; and, worse yet, the avoirdupois pound and the troy ounce are both so fundamental that neither one seems reasonable to change.

One thousand is divisible by eight. So one avoirdupois ounce is 437 1/2 grains. A unit of 2 1/2 grains is common to both the troy ounce (192, or 3 * 64, of them) and the avoirdupois ounce (175, or 25 * 7, of them) but they are relatively prime.

The division of an ounce into 8 drams, and each dram into 3 scruples, is not only applied to fluid ounces in liquid measure, but also to troy ounces in the apothecaries' scale of weight.

If a troy ounce is 24 scruples, then each scruple is 20 grains in weight.

Take 25 scruples; this is 500 grains, or 12 1/2 grains times 40. Whereas 437 1/2 grains is 12 1/2 grains times 35.

And so I could suggest that the troy ounce and the avoirdupois ounce be brought into harmony through the following device:

In addition to the troy ounce (480 grains), the dram (60 grains), and the scruple (20 grains), also define a unit of 24 grains, 20 of which make a troy ounce.

Wait a moment; dividing a troy pound into 12 parts to make troy ounces, and then into 20 parts... haven't I seen something like this before? Why, yes, but in the opposite order; a pound sterling is 20 shillings, each one of which is 12 pence. And, indeed, 24 grains is the unit of mass known as the pennyweight.

But now let us call the existing pennyweight the short pennyweight, and also define a long pennyweight of 25 grains. And an avoirdupois ounce is 17 1/2 long pennyweights, and the relationship between the troy ounce and the avoirdupois ounce is now clear and obvious!

Finally, there is liquid measure.

The weight of a fluid ounce of water, in the British Imperial system, as opposed to the U.S. customary system, is very close to one avoirdupois ounce. Unfortunately, while a pint is 16 fluid ounces in the U.S. customary system, it is 20 fluid ounces in the British Imperial system. The U.S. fluid ounce may be larger than the British fluid ounce, but it's not large enough for a U.S. fluid ounce of water to equal one troy ounce in weight.

If one calls the British Imperial pint of 2 1/2 cups a long pint, and also has a short pint of 16 fluid ounces, there finally would be a pint that's a pound (the world around!) creating a link between liquid measure and weight comparable to that in the metric system.

However, it is the U.S. gallon, at 231 cubic inches, that has some relation to the cubic inch; the British Imperial system of liquid measure has no such relation.

A British Imperial fluid ounce of water is 2/9 of 1% heavier than an ounce, so there is a bit of wiggle room. Could that fluid ounce be changed so as to be closer to an ounce in weight, and provide a link to linear measure as well?

A British Imperial gallon is 4.54609 litres, and a cubic inch is 16.387064 millilitres. So a British Imperial gallon is some 277.41943279... cubic inches. Change that to 277.375 cubic inches, and one has a whole multiple of the volume of a cube one-half inch on a side, at least. (Unfortunately, 2,219, while not a prime number, is 7 times 317, and so that does not lead to convenient dimensions for a rectangular prism with a volume of one gallon.) That would be 4.545361877 litres, making the modified fluid ounce equal to 28.40851173125 millilitres.

Even if the British Imperial gallon were simply defined as 277 cubic inches, an Imperial gallon of water would still weigh slightly more than 10 pounds; so under that system, an Imperial fluid ounce would be 28.37010455 ml; compare that to an avoirdupois ounce being 28.349523125 grams, and then take into account the fact that a kilogram of water occupies 1.000028 cubic decimetres (the old value of the litre, redefined in 1964 to be exactly a cubic decimetre), a British Imperial fluid ounce would weigh about 29.34955... grams.

There: a system of measurement, based on the British Imperial system of measures, so simple and rational that there is hardly any reason to prefer the metric system to it for the slight additional simplifications that it, admittedly, would still offer!

Of course, one could be a bit more radical. Abolish the avoirdupois system of weights, and define the gallon as 243 cubic inches, to weigh about the same as 128 fluid ounces of water, corresponding to the U.S. customary system of liquid measure, but somewhat larger in size. Here, a fluid ounce of water would weigh slightly less than one troy ounce, but a pint would be a pound of 16 of those ounces rather than a troy pound of 12 troy ounces.

Rather than switching to base-12 numeration, one could of course devise a completely decimal system of measurement, similar to the metric system, but using completely different base units. And if one can do that, one could use units taken from the British Imperial or U.S. Customary systems for that purpose.

As people who object to the metric system generally don't like the metric system, would this sort of thing really satisfy anyone? Or, more to the point, would it serve a purpose?

If Britain had switched over to such a system ages ago, back when the metric system was first proposed, then it would have served a purpose: they could have had all the convenience of the metric system without changing all the standard measures which supported their system of metrology.

Since the French standard metre rods were simply of better quality and accuracy than the British standard yards, for example, and this generally applied to the other fundamental metric standards as well, this, while an apparent saving of trouble, in the long run wouldn't really have been a benefit.

Looking at this option, though, what units could have been chosen?

In the case of temperature, obviously using the Fahrenheit scale for temperature, and degrees Rankine for absolute temperature, would be no more complex than Celsius and Kelvin.

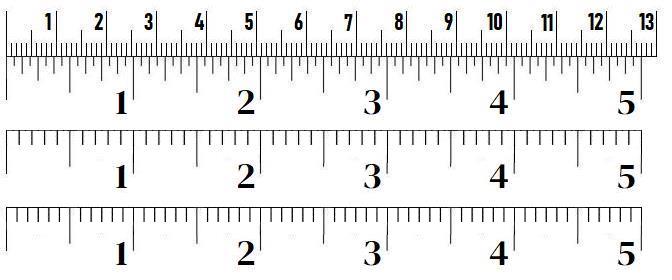

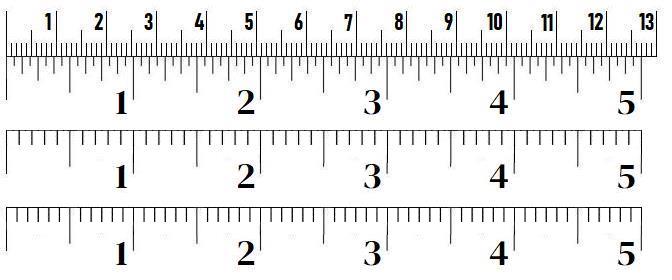

For distance? One genuine advantage of the Imperial system over the metric is that while metric rulers always only show centimetres being divided into ten millimetres, one gets to divide the inch into sixteen, ten, or even twelve parts, which is a convenience for certain kinds of drawing.

Above is an illustration of how this worked.

The foot could be replaced by the dekainch easily enough, but it would also replace the yard and the metre as well.

Instead of miles, geographical distances would presumably be measured in dekamyria inches, for which we would obviously need a shorter name. Since "neo-verst" or "Anglo-verst" would still be too long, and "dist", patterned after the unit of area on which the hectare was based, is too confusing, perhaps we could name this unit of length the "Vist"; after all, a vista is a large thing, for which a vist would be an appropriate unit of measure. One of those would be 1 mile, 1017 yards, 2 feet and 4 inches in length.

If we measured the wavelength of light in nanoinches instead of nanometres or Ångstrom units, then, for example, the Helium d line, instead of being 587.56 nanometres or 5875.6 Ångstrom units would be 23.1359 microinches or 23,135.9 nanoinches; since there are 25.4 millimetres to the inch, there would also be 25.4 nanometres to the microinch.

The case of mass becomes more complicated, because there are two competing British Imperial scales of mass, both of which we would like to preserve.

If the fundamental unit of mass were made 40 grains, then 12 of these units of mass would be one troy ounce, and 175 of them would be exactly one avoirdupois pound.

So instead of a one-pound pad of butter being approximately labelled as 454 grams, instead of 453.69 grams, say, it would be accurately labelled with the round figure of 175 of the new mass units. That would hardly seem like much of an improvement over metric.

In troy or apothecaries' units, a dram of weight was 60 grains, so I suppose we could call this 40 grain unit of mass a drach; similar, yet different enough not to be confused with a dram, a grain, or a gram.

And then there's liquid measure.

A cubic inch is 16.387064 millilitres. So a British pint is about 34.68 cubic inches. So a mug holding 35 cubic inches of beer would be just as satisfying, and wouldn't lead to too great an increase in drunkenness.

And a 25 cubic inch mug would be better suited to the proportions of the human alimentary system.

However, a cubic centimetre is a millilitre, and a millilitre of water has a mass of approximately one gram. As well, there was the old claim that "a pint's a pound the world around". On the other hand, a cubic inch of water, having a mass of about 16.4 grams, compared to a mass unit of 40 grains, equivalent to about 2.59 grams... gives 6.32 drachs of water to the cubic inch, no longer a simple and direct relationship.

Given that the MKS system of metric units, rather than the cgs system of metric units, formed the basis of SI (Systéme Internationale), presumably the other units of physics would be derived from the dekainch, the kilodrach, and the second.