This projection is the conformal member of the family of conic projections.

The map in this illustration has its standard parallel at 40 degrees North latitude, suitable for a map of the United States.

With 50 degrees North latitude as the standard parallel, here is a projection covering the entire Northern hemisphere:

Although conic projections are most noted for their applicability to most parts of the world in their conventional case, they also offer flexibility in that their standard parallel can be varied to fit different shapes, and they can be subjected to coordinate conversions like any other projection.

One famous use of this projection in its oblique aspect is its use in the Bipolar Oblique Conic Conformal projection, which joins two oblique aspects of this projection. Slight inaccuracies are unavoidable at the place where the projections are joined, but the projection is elsewhere conformal. This illustration shows the two conic projections out of which it was constructed:

Conformal maps are particularly suited to depictions of extended areas, since they avoid the shape distortions most noticeable to the eye. The following map:

shows an oblique Lambert's Conformal Conic which covers Antarctica, Africa, Eurasia, and Australia, with its standard parallel an arc that travels through them all, shown in red on the map above. As can be guessed from the fact that the map is half a circle, the standard parallel is 30 degrees in the map coordinate system.

Nearly the whole world can be projected on the Mercator projection, and the same can be done for this projection, particularly if a standard parallel such as 10 degrees in the map coordinate system is chosen:

Of course, there is a much simpler way to make a map of the whole world using the conformal conic; to moderate the exaggeration of scale towards the north in the Mercator somewhat, simply make 10 degrees North the standard parallel:

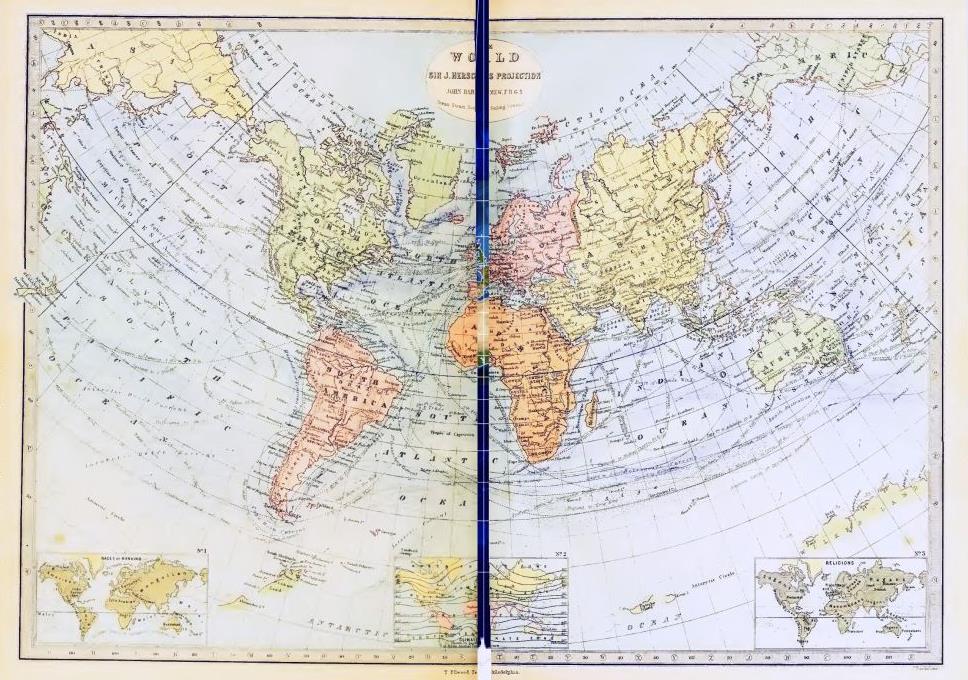

Around 1880, maps were printed on a very similar projection, Herschel's projection. This had a standard parallel of 14.477... degrees, so that angles from the pole of the projection would correspond to 1/4 of the longitude:

I had found an old map from a book in the public domain that I could present here, but as some of the map was lost in the gutter, I created a map on the same projection, and matched the scale, so that I could fill in the missing part for the following illustration:

as I didn't want to pass up the opportunity to show what it had looked like back then, but I wanted the map to be complete (although I didn't bother with making a tiny Mercator map to fill in the inset map at the bottom).

Even then, it appears that the exaggeration of areas on the Mercator projection may have been a concern: but as this projection not only provides a small improvement in this area, but is also still conformal, like the Mercator, I see this as an attempt to address the issue, but by means of taking baby steps away from the Mercator rather than huge leaps.

Also, Herschel being an astronomer - the discoverer of the planet Uranus - it would not surprise me at all if he had chosen such a standard parallel so as to repeat the projection on a disk which could rotate counterclockwise in a clock, as illustrated below:

so as to indicate the current time of day in every Standard Time zone worldwide. Clocks of a similar style of mechanism are made and sold today. Or, of course, one can have just one copy of the map that stands still, and have a disk or ring bearing the different times that rotates.

Among the makers of clocks on similar principles are Seiko, Keininger and Obergfell (under the Kundo brand), and Howard Miller. Generally, however, they use the polar case of the Azimuthal Equidistant, and such a clock was also part of the Spilhaus Space Clock, on the lower right, but at least one clock by Howard Miller instead used a cylindrical projection with the times on a belt. There is also the Geochron World Clock where a repeated map on a cylindrical projection is on a belt. Also, instead of a map, simply a ring with labelled dots indicating the longitudes of major cities may be used; this is apparently even more common.

Many of those who claim the Earth is flat propose that the real shape of the continents on its surface resembles an Azimuthal Equidistant projection centered on the North Pole; this would allow a flat earth to be circumnavigated. However, either one leaves Australia as it is on that projection, meaning that East-West distances in Australia would be larger than claimed by conventional maps, or one shrinks Australia, so that it would not span as many time zones as conventional maps show. It would be possible to test this by putting webcams on a couple of sundials, say one in Sydney and one in Perth, and by taking an automotive journey between Sydney and Perth, as I point out on this page.

On that page, I have now added an image of a map of the world on Lambert's Conformal Conic projection with 50° N and 30° S as standard parallels. It turns out that such a map occupies very nearly 1/5 of a circle.

A Lambert's Conformal Conic with one standard parallel at 11.537 degrees North latitude, so as to make the conic constant almost exactly 1/5, looks like this:

This would prevent refuting the notion of a flat Earth easily by travel in the most accessible parts of the world, but it would require the flat Earth to have five identical Suns circling above it (with synchronized sunspots! Ah, but they could all be reflections of a central fire...) and circumnavigation would no longer be simple.

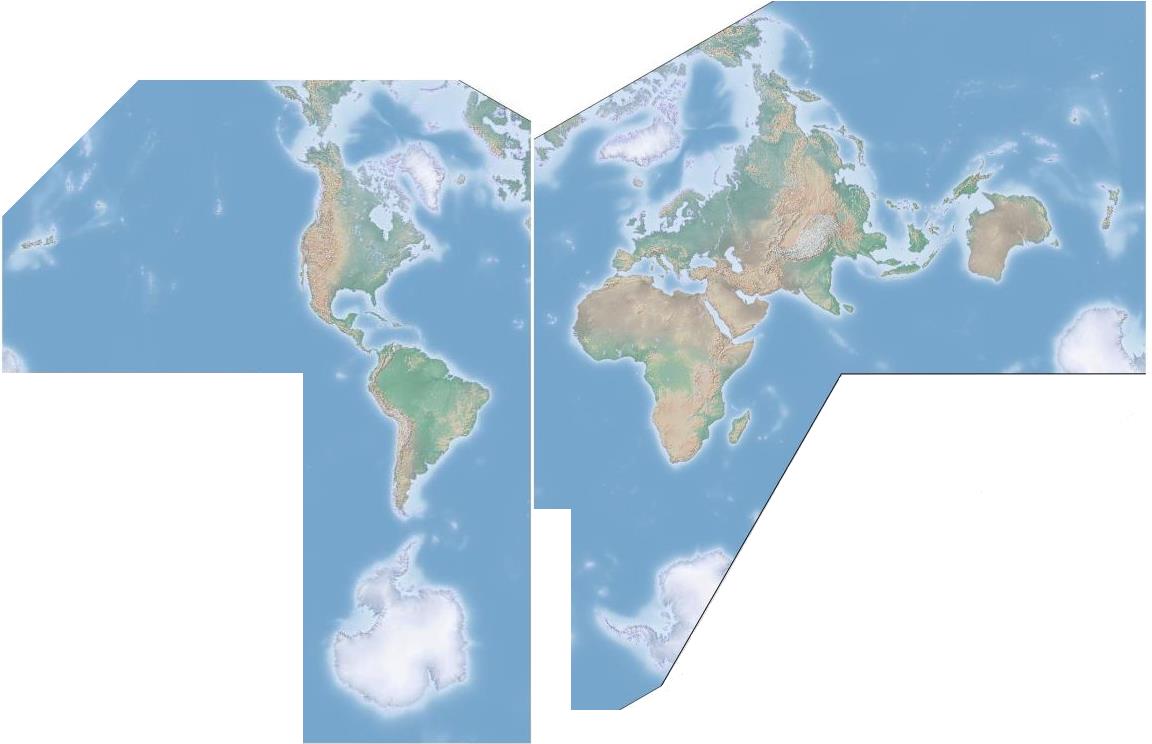

Another possibility is to divide the world into an Eastern and a Western hemisphere, in much the same way as was done for maps of the whole world using the Stereographic projection for each hemisphere, but use a conic conformal projection for each hemisphere:

In this form, the general appearance of the projection is reminiscent of that of the Butterfly projection of B. J. S. Cahill, but the world is only divided into two parts, not eight. Incidentally, B. J. S. Cahill was also a noted San Francisco architect, in addition to devising several map projections based on the octahedron; thus, he has more than one thing in common with R. Buckminster Fuller, also an architect, who also developed two polyhedral map projections, one based on the cuboctahedron, and one on the icosahedron.

Since the projection is a transverse case of the conic conformal, it is not too horribly sophisticated mathematically (compared with map projections such as the developments of August's Conformal Projection of the Sphere on a Two-Cusped Epicycloid, to be seen later); the standard parallel for each conic projection is 40 degrees from the map equator (that being the two parallels of 20 degrees West longitude and 160 degrees East longitude) and so areas are kept from being distorted too heavily, and the map is conformal, so all the shapes "look" right. That last property is sometimes scorned as a deceptive one these days, but I do think that the projection shown above would not be such a bad choice for a wall map for use in schools. The only serious problem that I can see is that it would be nice to be able to rotate the map so as to put North at the top for any part of the world being specifically examined.

Presumably, the projection could be extended slightly to allow Greenland and Iceland to be kept in one piece, and perhaps even to continue Eurasia up to the Bering Strait; Stereographic inset caps could be used for the Arctic and Antarctic as well; also, the conic projection would only have to be continued, not extended, to split Antarctica into only two halves, instead of four pieces, with the additional advantage of reducing the width of the map.

When such areas of overlap are created, the two hemispheres might also be less strongly rotated to favor the North Atlantic, so as to leave North closer to the top without having to rotate the map.

The best orientation for the two hemispheres is, however, a matter of taste, and a bit more rotation, to favor Europe and the Eastern Seaboard of North America, and even Africa and South America, might, for example, be preferred. An example of this, but retaining perhaps a bit too much rotation, also involving changing the standard parallel slightly, to about 41.8103149 degrees, to make it easier for me to perform the rotation that allows Antartica to be kept to only two pieces produced the projection illustrated below:

Perhaps the simplest solution, letting the Equator as it runs through South America and Africa, would be best. The slight movement of the standard parallel seems to have improved the appearance of India noticeably; perhaps even a parallel of 45 degrees should be considered.

Although this world map definitely depicts the continental areas with a pleasing appearance, no projection of the globe on a flat piece of paper is perfect, not even this one. Enlargement of some parts more than others does noticeably distort the shape of India, Greenland, Australia, and Mexico, as well as that of Russia's eastern portion, Siberia, even if the duplicated portion beyond the normal limits of the projection is excluded, and, although the projection does divide the world into only two pieces, it is still, in a sense, more "interrupted" than the more conventional projection of two Stereographic hemispheres. Another defect that may be imputed to it is, of course, the lack of uniformity in the orientation of the compass points.

Still, I liked it enough that I wanted to make the best possible image of this projection. Using a freely available relief map from the Natural Earth web site, and using two passes in G.Projector, one to produce an obliqued Plate Carrée projection, and the next to make a Lambert Conformal Conic from it, since it doesn't allow that projection to be obliqued, I was able to produce:

The idea of using the Lambert Conformal Conic projection as a better way to depict a hemisphere than the Stereographic, and then using it for a world map in two hemispheres, is not original to me. Using the standard aspect of the projection, and a standard parallel of 30 degrees (given as using two standard parallels, at 10 degrees and 48 degrees and 40 minutes), a projection of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres was devised by Commander A. B. Clements of the U. S. Shipping Board, and noted in Elements of Map Projection by Deetz and Adams.

The hemispheres were each repeated twice, so that the projection was in two circular pieces which could be rotated together to bring any point on the Equator into contact. It is depicted at right.

The Lambert Conformal Conic projection is derived from the stereographic projection, which follows the rule:

90 - lat

r = tan( ---------- )

2

by knowing that the standard forms of most mathematical functions when applied to complex numbers produce conformal mappings, and the effect of raising a number to a power in complex numbers is to raise its distance from the origin to that power using conventional arithmetic, and to multiply its angle from the x axis by that power.

Since on any conic projection with a standard parallel at lat_sp, the angles are reduced by being multiplied by sin(lat_sp), then it follows we can raise the stereographic r to the power sin(lat_sp) to get the radius from the pole for any parallel of latitude in the conformal conic.

More complicated calculations allow one to determine for what standard parallel the scale at two other parallels, north and south of it, will be equal. Then, the scale of the map can be given as the scale on those parallels; although the projection is the same, this is known as the version with two standard parallels, since at those two parallels the scale is correct, even if the curvature of the parallel is correct for another parallel between them.