The question that forms the title to this page might seem a strange one.

After all, a violin doesn't seem to be a complicated contraption with moving parts, except for the tuning pegs, and it's fairly obvious what they are there for.

However, when they are bowed, the strings of a violin obviously do move, at least a very short distance; not only is this visible, but in the absence of vibration, a violin would make no sound.

And the body of a violin is a hollow box which allows the violin to produce a louder sound than the strings would produce by themselves. This already needs some explanation. After all, a regular acoustic violin doesn't need batteries, so without a source of power, how can it amplify a sound?

Of course, it doesn't. In electrical terms, what the body of a violin behaves like is a transformer: it performs impedance matching between the strings and the air, so that more of the energy of the strings' motion can impart motion to the air. The strings are small; they move the much larger surfaces of the violin, so now they're grabbing hold of more air.

When the strings are bowed, they move from side to side, in a pattern closely resembling a sawtooth waveform. And thus, on a simple synthesizer - or the SID chip of a Commodore 64 computer, as I can vouch for from personal experience - one chooses a sawtooth waveform when one wants to make a violin-like sound.

The strings move from side to side, with the violin beneath them. How, then, does the bridge of a violin do anything more useful than slide along the belly of the violin from side to side?

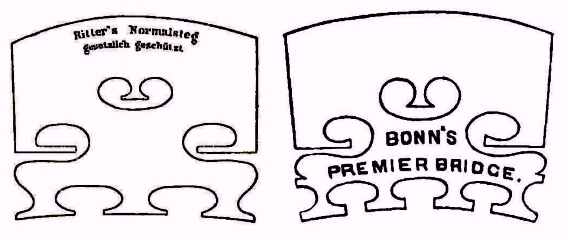

The diagram above attempts to answer that first question. The violin bridge in the diagram looks different from real violin bridges, in order to make its function more obvious: an actual bridge intented to be similar to this example might look something like this:

as it is desired for violin bridges to be decorative in appearance - and the additional wood left present often performs a useful function in modifying the resonances of the bridge.

The tension of the strings holds the bridge firmly against the body, so the feet can't easily slide from side to side. But the shape of the bridge is chosen so that the side-to-side motion of the strings tends to cause the bridge to tip over from side to side. Thus, its two feet move vertically, in a direction perpendicular to the surface of the belly of the violin, thereby being effective in making its whole area push on a large amount of air.

There's just one problem. While one foot pushes down, the other one is going back up. So it looks as if a lot of this motion, although it's in the right direction, is going to cancel out.

To see how this problem is dealt with, we need to take a look inside the violin.

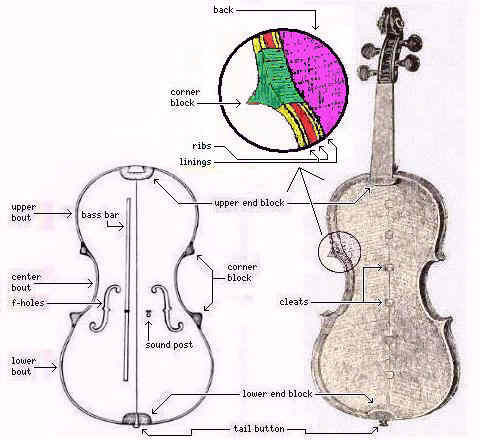

In the image on the left, the diagram on the left side, although it shows the f-holes to indicate that one is looking at the diagram from the front of the violin, and to give a reference as to the position of everything in the diagram, does not depict the belly of the violin. The ribs are too thin to show in a diagram at this scale as solid bodies, but rather they form the border line around the corner blocks and the linings, which are visible.

The ribs of a violin are the outer walls of the violin's body on the side, between the back and belly plates. The linings are two (actually twelve, two for each of six parts of the ribs, since they're interrupted by the blocks) thicker strips of wood, attached to the ribs, one where they touch the belly, and one where they touch the back. The extra area they provide allows the back and the belly to be glued to the ribs securely.

Although a violin looks nearly symmetrical from the outside, on the inside the two feet of the bridge are treated differently.

One foot has the "bass bar" beneath it.

The belly, or front surface, of a violin is made of a soft wood like spruce or pine (Stradivarius always, or almost always, used spruce).

The bass bar runs across a large portion of the height of the belly of the violin. This helps the foot of the bridge that lies above the bass bar to move a large portion of the belly of the violin. The bass bar is made of spruce, like the belly; instead of being carved to fit the belly exactly, it is often made slightly flatter, so that there is a certain amount of built-in spring tension when it sits in its normal position. Of course, this must not be overdone.

The back of a violin is made of a hard wood like maple, sycamore, or pearwood (Stradivarius always, or almost always, used maple). Poplar, or some types of willow (while willow is usually thought of as a softer wood, there are harder varieties, and willow and poplar trees are closely related), is another possibility: although only occasionally used for the back of a violin, these woods are more often used for the back of a cello, and Stradivarius did so himself. The other foot of the bridge sits (with the belly of the violin in between, of course) almost on top of the "sound post", a wooden peg made of a soft wood, like spruce or pine, which connects the belly of the violin to the back of the violin.

Since the back of the violin is made of a harder wood than the front of the violin, that foot of the bridge now won't move as far as the other foot, which pushes on only the front and not the back. So the two feet don't cancel each other out.

The back of the violin does move, though, and in the opposite direction to the front of the violin. So together they either expand or contract the interior of the violin at the same time, with a bellows action.

The only problem with this otherwise ideal arrangement is that the sound directly radiated from the top of the violin will, therefore, be opposite in phase from the sound coming out of the f-holes in the top of the violin. Given the usual manner in which a violin is held by a performer, however, this is more of a problem for the cello and the double bass than for the violin or the viola.

This analysis is an oversimplification; the speed of sound is finite, and given the frequencies of notes played on the violin, this is significant for its acoustic behavior; so instead of being opposite in phase to sound from the belly plate, the phase relation of sound from the f-holes to sound directly radiated from the belly plate will depend on frequency.

Oversimplified though it may be, this basic description of a violin's function is sufficiently close to the reality that I am rather surprised that improved violin bridges with three or four feet, instead of two, as illustrated above, were seriously offered for sale as an improvement.

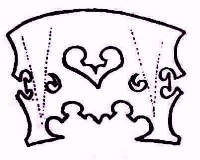

From this perspective, the bridge design above, proposed in the July 1897 number of a magazine about violins, as an improvement as it remedies what is seen as a defect in conventional bridges, the lack of a direct straight-line path for the vibrations of the strings to travel to the feet of the bridge (the paths provided by this design are shown by the dotted lines) is even more mistaken, as it is precisely because the bridge provides no such direct path that the direction of the vibrations is rotated from one that is unable to contribute much to the sound of the violin to the direction in which the greatest contribution is made.

On the other hand, this design, advertised around the same time, as the "Uniformity" bridge, is sound in that it would perform the basic function of a violin bridge about as well, and in the same way, as a conventional bridge. That does, of course, not mean that the way in which it filters the frequencies from the strings, compared to what a conventional bridge does, would be superior; also, its appearance is less decorative, and more mechanical and austere, which would have counted against its popularity.

Also, given that the sound post's two purposes are to transmit vibration to the back, which is made of maple, or another hard wood, and to reduce the excursions of the motion of the foot of the bridge near it, by transmitting the stiffness of the back forward, one would have thought that the sound post should be made from the same hard wood as the back, if not possibly one even harder.

The reason that instead a soft wood, like that used for the belly of the violin, is used is that the sound post is not glued in place, and so it must have the ability to be squeezed so that it can hold itself in place.

Based on this understanding, I wondered if the violin could be improved by replacing the f-holes on the belly with an aperture of the same size elsewhere; for example, on the upper bout, near the neck of the violin, on the side opposite the chin rest.

I see, however, that a similar idea has been had elsewhere, although in a case where the circumstances are different: the German luthier Thomas Ochs produces his own version of the Kasha guitar design by Michael Kasha with the sound hole placed on the side of the instrument.

Also, in the immediate postwar period, Julius Zoller made violins which had a set of small sound holes in the side instead of f-holes; however, these violins differed from conventional violins in other respects as well; their shape was different, and they had an extra string for sympathetic vibration.

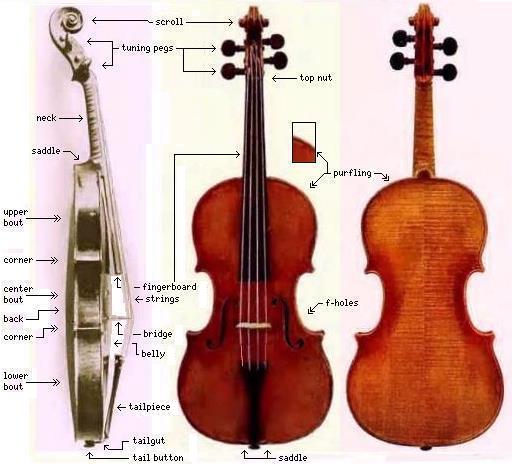

To assist with the discussion that is to follow, I am adding two diagrams which illustrate the different parts of a violin. Incidentally, rather than attempt to draw a picture of a diagram myself in a paint program, I have used illustrations from old books in the public domain as my starting point. It may be of interest to note that the photographs of a violin used in the diagram immediately below are of the Earl Stradivarius, named after the Earl of Westmoreland, and they came from a book with photographs of several of the violins in the collection of Royal De Forest Hawley.

In the first diagram above, one thing to be noted is that two completely different parts of the violin are called the "saddle" of the violin by different sources.

According to a diagram of the parts of the violin I saw on one site, the curved portion of the neck of the violin, near where it joins the body of the violin, is the saddle.

Other diagrams use that term to refer to a small rectangular piece of wood which protects the belly of the violin, and its purfling, at the bottom from the pressure of the tail gut. This part is sometimes also called the "rest", not to be confused with the chin rest, not shown in these diagrams.

Speaking of small pieces of wood, the image of the ribs and back of a violin included in this diagram shows a number of small square pieces of wood along the central seam of the two-piece back. These are called cleats; normally, they are not part of the original construction of a violin, but are instead glued to the back when it is being repaired for that seam having come apart.

As we've already noted, the body of a violin has a back carved from a piece of maple, or sometimes another hard wood, and a front, called the belly, carved from a piece of spruce, or sometimes another softer wood.

Around the sides of the violin, maple is also used. In this case, thin strips of maple are bent using heat, to form the upper bout, the two center bouts, one on each side, and the lower bout. These are held in place by carved solid blocks of woood, the corner blocks.

As well, the upper end block and the lower end block brace the upper and lower bouts.

I had thought that the corner blocks, at least, must be of maple to match the appearance of the bouts, but that was due to confusing the linings with the ribs in some diagrams I had seen. The diagram to the right is intended to clarify this issue. The linings are interrupted by the corner and end blocks of the violin, but the ribs continue over them and cover them.

In the diagrams of the parts of a violin shown on this page, the linings of the center bout are shown as extending into the corner blocks, rather than being butted against a solid corner block. The latter is given as a usual contemporary practice, at least in the Victorian era, while having the linings continue into a space mortised for them in the corner blocks is noted as a specifically Stradivari practice. However, Guarneri did it that way as well, and so did the Amatis. On at least one violin, Guarneri varied the practice by making the portion of the linings mortised into the corner blocks wedge-shaped, so that it came to a point; this was also the usual practice of Carlo Bergonzi, and it would have the benefit of simplifying, in one respect, the process of hollowing out the needed spaces in the corner blocks.

I have since read that the corner blocks are usually of spruce or pine, along with the upper and lower end blocks; however, Stradivarius used willow for those parts of the violin. But Guarneri del Gesù did use spruce for them, so later makers are entirely justified in dispensing with the need for one additional type of wood.

The ribs, of course, extend across the entire distance between the back and the belly of the violin, as they seal the edge of the violin, and hold those plates in place. The linings, however, are at both the top and the bottom of the ribs, and extend only for a short distance on each of those sides; as the ribs are very thin, usually about 1 mm or 1/24" (1.06 mm) (3/64" (1.19 mm) would be, of course, a more natural distance before the metric system was adopted, and one reference gives 1.2 mm as the approximate thickness of the ribs on a guitar by Stradivari, another gives that as what has eventually become the standard for the thickness of the ribs of a violin (and I have also come across one page on violin construction which gives the appropriate range of rib thickness for a violin as 1.1 to 1.3 mm, which specifically states that anything less than 1.1 mm is "unacceptable"); a distance of 1.12 mm would correspond closely to four Cremonese atomi), the linings provide an additional surface to which the back and the belly can be glued.

As a cello is much larger, its ribs have to be somewhat thicker, 1.5 to 1.7 mm being given by one source. Maple ribs that are 2mm or 3mm could still be bent by the method used in violin making, but the thickness of the ribs is significant to the sound of a violin, and overly thick ribs have been found by experience to be detrimental.

One web site gives 1.1 mm as the appropriate thickness for the ribs of a full-size violin, but for violins that are 3/4 size or smaller, 1 mm is given instead. That site also notes that the linings are 2mm thick on a full-size violin; from looking at photographs, I had estimated that the linings were 2.5 times as thick as the ribs instead, and, indeed, from making more careful measurements on a photograph of linings and ribs by Stradivari, I have found that the linings shown there were very close to 3 mm thick. But then, willow is a very light wood, so that linings of spruce or pine would need to be thinner is quite reasonable.

The top nut is a protruding part at the top of the fingerboard against which the strings rest as they come from the tuning pegs and go to the bridge. This minor part serves two important functions: it defines the lengths of the open strings (that is, it defines how long the vibrating part of the string is when the fingers aren't pushing the strings against the fingerboard to shorten them for playing a higher note), and it ensures the strings are a distance above the fingerboard right from the start on their way to the bridge.

Usually, on a violin, the nut is made of ebony like the fingerboard. Bone, hard plastic, or a metal (such as brass) are alternate possibilities.

The tailpiece, which holds the far end of the strings, isn't permanently attached to the body of the violin. Instead, it has a metal rod, bent into a U-shape, and also bent towards the back of the violin, called the tailgut, which hooks on the tail button of the violin. The tension of the strings holds it in place, against the saddle at the bottom of the violin.

The fingerboard is usually made of ebony. It does not have frets, unlike the similar part of a guitar; one of the features of a violin is that, like a trombone, it can play notes that are continuously varying in pitch, with no striking change in sound quality between pitches that correspond to the piano keys and those that are between them.

Incidentally, note that the corners of the violin, due to the fact that the corner blocks are solid, are not part of the shape of the interior of the violin. This has been used in the shape of some modern violins made of carbon fiber, which omit the corners in their external shape - and, as well, in the nineteenth century experimental violins made by François Chanot had this form, as well as having f-holes of a simplified shape.

The bridge of the violin, with which we began this page, also has several parts which are named: in addition to the feet, the name of which is obvious, the spaces typically present have names as well which are related to parts of the human body. The spaces joined to the sides and in a symmetrical pair are referred to as the "kidneys" on one web site selling violin bridges, and as the "ears" in a paper about the violin bridge and its resonances, and simply the "ovals" in yet another place; it's possible the term "kidneys" is a translation of the term used in a language other than English.

Also shown, on the right of the diagram, is the bridge of the cello. That of the viola looks much like the bridge of a violin, only larger, and that of the double bass looks much like the bridge of a cello, only larger. Thus, the bridges of the larger instruments are considerably narrower in relation to their heigh; also, as we will see on a later page, the bridge of the cello retains more baroque characteristics, most obviously in the shape of the heart.

Stradivari never made a violin without corners, and yet there exists an authentic Stradivarius violin without corner blocks, the 1726 Chanot-Chardon, also known as the "Guitar Strad", not to be confused with the Sabionari, the one of several actual guitars made by Stradivari which is currently in playable condition. How can this be?

No, someone did not take a Stradivarius violin with corner blocks, and radically change it to remove the corner blocks. But this does involve some radical surgery on a musical instrument by Stradivari.

What Stradivari did make without corner blocks was (it is believed; in the absence of records, we don't really know for sure) a viola d'amore, which is a musical instrument somewhat resembling a violin, but more specialized in function - it has drone strings, like the drone pipes of a bagpipe, among other differences - and the viola d'amore is seldom used these days. Since this has been true for a long time, even before the violins of Stradivari became museum pieces, someone decided that he would rather have a genuine Stradivarius violin (or at least a violin embodying the virtues of a string instrument made by Stradivari himself, since one could quibble) to use regularly for the music people wanted to listen to, than an instrument by Stradivari that would mostly gather dust.

I was able to find an old image of a Chanot violin, but it had a heavy Moiré effect, so I had to process it somewhat heavily: